A short introduction to the life of Thanasis Veggos

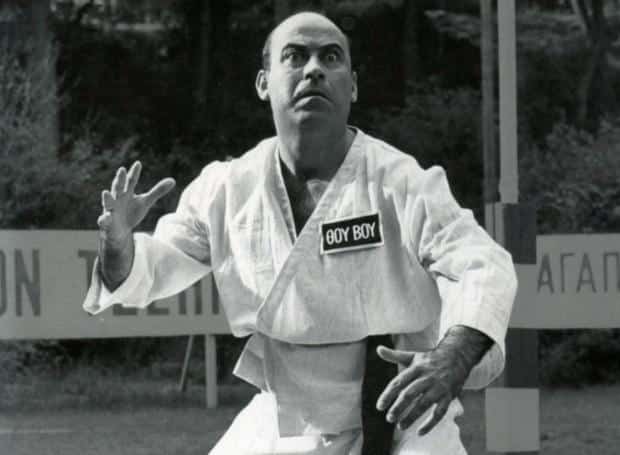

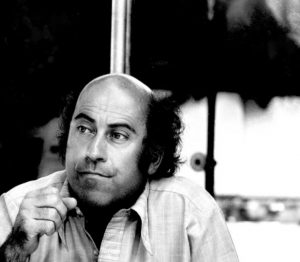

Thanasis Veggos was one of the best comedians of the greek cinema of the 60’s and 80’s . He continued his appearance on the theatre and the movies until the new millennium.

Veggos was born on May 29, 1926 .Though he made dozens of films that had success among the greek community , he went through several financial difficulties in his professional career.

Veggos was born on May 29, 1926 .Though he made dozens of films that had success among the greek community , he went through several financial difficulties in his professional career.

His father was his personal hero, and he tries in every way to do what he knows best: to show him his love.

In a 2009 interview, actor Kostas Kakavas described the deep affection beloved Thanasis had for his father:

“You can’t imagine how tender and sensitive he is! Just think—he once told me: ‘Kosta, I saved money and never picked up smoking so I could buy cigarettes for my father, who was poor. And now that I’ve finally made some money, he’s no longer alive to enjoy a better life. I didn’t take him as many cigarettes as I should have.'”

Very few people know that Vasilis Veggos briefly appeared in the first film his son played in, “Magic City”, during a scene where the poor neighborhood collects money to save young Kosmas’ (Giorgos Foundas) truck from the hands of a black marketeer (Stefanos Stratigos).

Young Thanasis grew up in poverty, working from a young age doing odd jobs and in leather-processing workshops. During the Occupation, he joined EPON, and in March 1949, he was forced to serve his military service on Makronisosas an “undesirable,” where he developed his well-known obsession with cleanliness.

The painter and set designer Tassos Zografos writes in his biography:

“He was nervous, restless, anxious about everything. But he was also patient and helpful. The least of his fears was Makronisos. He was far more afraid of dust—not germs. He’d slice an onion into his pasta and eat whatever was left in someone else’s mess tin without disgust. But he couldn’t tolerate dust. Or disorder. We happened to sleep in the same tent. During the summer, it was unbearably hot, and we would lift the tent flaps to let in some air. But with the air came dust. Thanasis couldn’t stand it. As soon as we dozed off, he’d go and close them again.

Veggos was just like he is now—obsessive about cleanliness. We barely had water to drink, and he was busy brushing off lint from the inside of his pockets. Pristine pockets, obviously, since we had nothing to put in them. When Thanasis arrived, Giannis Goumas told me that a kid from his neighborhood had come, a real character. He added that Thanasis wanted to become an actor, and that we should give him some of our bread, since he was always hungry. So we’d give him whatever was left from our dry rations. And Veggos, just like now, was tireless, running around the island like a cross-country champion. He didn’t even smoke, unlike most of us.”

It was there that he had his first audition, from the head of the island’s makeshift theater—but he didn’t make the cut…

It was there that he had his first audition, from the head of the island’s makeshift theater—but he didn’t make the cut…

Everything changed for the well-meaning Thanasis when Nikos Koundouros entered his life—or rather, when Thanasis entered Koundouros’ life, to do—what else?—help him.

The famous director recalls their first meeting:

“I had gone to the top of a mountain, with the administration’s blessing, to set up my tent and my life. As I sat there wondering how to start, all alone with a single tent thrown on the ground, a hatchet, and some stakes, I saw a strange figure approaching—wrapped in one of those filthy, torn overcoats they gave us. He came carrying planks from crates and a hammer. He built something—a sort of platform with the planks—and then he suddenly said:

‘Comrade’—a blessed word that has since become a stigma—‘Comrade, you’re going to die,’ he said. ‘It gets cold at night. Put your blanket over the planks.’

I said, ‘Why do you care if I die? You’ll die too.’

He didn’t laugh. He didn’t not laugh either. He just took the tattered tent and started setting it up between the stakes. I watched him, thinking: this guy is either crazy or a saint. Then again, it’s all the same—crazy or saint.”

When Koundouros, along with Tassos Zografos, took on the task of building a theater on the island of suffering, he asked the authorities to give him “that half-crazy soldier.” They began constructing it together, with Veggos taking on every task until he finally stepped onto the stage for the first time—earning a round of applause and the full acceptance of the entire battalion.

His first battle with an audience had been won—and would follow him throughout his life.

In one of his very few interviews, published in the magazine “os3”, Veggos spoke about that beginning:

“I remember, when I was on Makronisos in ’49, in the performances organized by Nikos Koundouros at the little theater in the Second Battalion. He’d give me the mic, and I’d just say whatever came to mind. I’d do impressions, parody commercials for women’s creams—anything. Everyone laughed. I kept wondering—how on earth am I funny?

That’s where I first saw real theater. I saw Katrakis and other great actors perform. Koundouros had spotted something in me and believed I could act, so he had me doing all sorts of things—more like a clown, really.”

In truth, Thanasis Veggos didn’t just take away theater from Makronisos—but he never spoke of the rest.

It’s like asking a saint to talk about his miracles. The only thing he ever repeated, with his legendary humility, was that he was never a resistance fighter and had ended up there by mistake.

To understand how the “good man” felt about that place of torment, we must turn to an account by his friend, director Dinos Katsouridis:

“They didn’t do anything to me on Makronisos, compared to what they did to others. I’m not talking about the threats, the beatings, the hunger, the humiliation, the torture.

I’m talking about the shame. For those who couldn’t take it. Who later turned against their own comrades.

That—no one can stomach.

It’s the bankruptcy of humanity—both of the one who conceives it in his diseased mind and of the one forced to accept it.

Even the Middle Ages wouldn’t dare.

But they did.

And they even had the nerve—and it was someone intellectual, like Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, no less—to say that Makronisos was the ‘new Parthenon of Greece.’

Shame on them!”