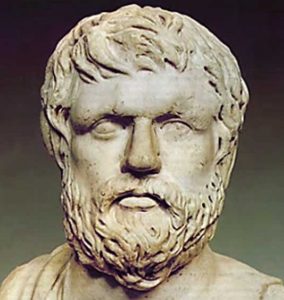

Xenophon his life and works

Xenophon was born around 430 BC in Athens. He came from a well-off family belonging to the deme of Erchia, and he was part of the equestrian class. He studied under Socrates, to whom he dedicated a significant portion of his work. Socrates’ teachings had a profound impact on the young Xenophon, although he was eventually drawn more to a life of action and military career than to philosophy.

Childhood

Diogenes Laertius tells us that once when he was still young, Xenophon met this Socrates in a narrow street and with his rod blocked his further course and asked him, among other things, “where do people become good and virtuous?” Xenophon being at a loss then, Socrates answered him “Where did you guess!”. Since then Xenophon has been a student of Socrates who considered him a role model.

Diogenes Laertius tells us that once when he was still young, Xenophon met this Socrates in a narrow street and with his rod blocked his further course and asked him, among other things, “where do people become good and virtuous?” Xenophon being at a loss then, Socrates answered him “Where did you guess!”. Since then Xenophon has been a student of Socrates who considered him a role model.

Xenophon grew to manhood with the association of donating noble youths of Athens whose main occupation was sports, he remained throughout his life a lover of wrestling and free games, and from his works it is clear that he was an excellent horseman.

After the fall of the Thirty Tyrants and the restoration of democracy, Xenophon accepted the offer of his Boeotian friend Proxenus and decided to join the mercenary army of Cyrus the Younger, who was planning to dethrone his older brother Artaxerxes II, the King of Persia.

However, Cyrus’s death at the Battle of Cunaxa in 401 BC and the assassination of the most important Greek generals by Tissaphernes forced the mercenaries to retreat through Asia to Byzantium. Xenophon, chosen along with others to lead the great retreat of the “Ten Thousand,” successfully guided the Greek mercenaries to the shores of the Black Sea and then to Thrace.

His adventures in Asia did not end there. In 396 BC, he followed the Spartan king Agesilaus in his campaign against Persia. Xenophon admired Agesilaus greatly, so much so that two years later (394 BC), he fought alongside him against the Athenian army at the Battle of Coronea. For this act (although ancient sources also cite his participation in Cyrus’s campaign as the reason for his exile), his fellow Athenians exiled him.

Agesilaus, however, compensated him by granting him an estate in Scillus, where Xenophon retired for the next twenty years. He left the estate in 370 BC when the Eleans captured Scillus. After Sparta’s defeat by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC), he sought refuge in Corinth.

Although his exile was revoked (due to increasing pressure from Thebes, leading to a rapprochement between Athens and Sparta), it is uncertain if Xenophon ever returned to Athens. However, we know that his two sons served as cavalrymen in the Athenian army at the Battle of Mantinea in 362 BC, where one of them, Gryllus, was killed. Xenophon died around 355 BC

His works

Xenophon was a prolific writer. His reputation as a historian primarily rests on his works “Hellenica” and “Anabasis of Cyrus.” The historical context is also present in “Cyropaedia” and “Agesilaus,” his two biographical works. However, because Xenophon narrates events in “Cyropaedia” with great freedom, this work is essentially an early historical novel, while the emphasis on Agesilaus’s virtues gives the eponymous text an encomiastic character.

Xenophon’s works dedicated to Socrates and his teachings include “Memorabilia,” “Oeconomicus,” “Symposium,” and “Apology of Socrates.” Lastly, there are texts with technical, ethical, and political content, including the treatises “On Horsemanship,” “Hipparchicus,” “Hunting,” “Constitution of the Lacedaemonians,” “Ways and Means,” as well as the short dialogue “Hiero.”

Hellenica

Xenophon’s principal historical work presents the history of Greece from 411 to 362 BC in seven books. His narrative begins with the phrase “after these things”, exactly where Thucydides’ account ends. The abrupt start, combined with the unusual absence of a preface for ancient Greek historiography, indicates Xenophon’s intention to link his history directly with Thucydides’. The work is divided into two parts. The first part deals with the end of the Peloponnesian War, while the second part covers events up to 362 BC.

Specifically, the remaining part of the second book details the history of the Thirty Tyrants regime until the restoration of democracy in 403 BC. The third and fourth books, and up to the first chapter of the fifth book, recount the conflicts between Sparta and Persia and the Corinthian War up to the Peace of Antalcidas (387/386 BC). The final part of the work (books five to seven) covers the Spartan hegemony until the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC) and the Theban hegemony until the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC).

Unlike historical monographs, Xenophon’s narrative does not focus on a single war but follows developments from 411 to 362 BC across the entire Greek world. While the activities of Sparta occupy the most significant portion of the work, reflecting what some believe to be Xenophon’s pro-Spartan bias, Xenophon often maintains a critical distance from Spartan decisions and does not hesitate to highlight their failures. He also devotes considerable space to the actions of other major Greek cities.

The prominence of Sparta in the narrative is primarily due to its critical and leading role during the period covered by the work. The dramatic changes Sparta experienced, losing its dominant position in Greece within a few years, provided Xenophon with a particularly interesting subject and a prime opportunity to apply his ideas about the art of governance and good leadership at the level of city-states.

As a narrative text, “Hellenica” possesses several virtues. Xenophon is distinguished by the vividness with which he recreates his material. His military experience is evident in his descriptions of battles and military operations. The numerous speeches in the work illuminate and elucidate the personalities of the speakers.

First-person narrative interventions are absent in the first part of the work (up to 2.3.9), but in the subsequent books, the presence of the narrator becomes more pronounced. The inserted comments usually aim to enhance the audience’s understanding of the narrative and rarely concern methodological issues, although in some cases, the narrator refers to the criteria by which he included the events he describes.

Xenophon’s presence is also evident in the comments evaluating the characters and the various behaviors recorded in the narrative. His didacticism and the impressive immediacy of his descriptions are characteristics of his work that mark him as a precursor to similar, very prevalent trends in Hellenistic historiography.

Cyrus Anabasis

This work recounts, in seven books, the adventures of the Greek mercenaries who participated in the campaign of Cyrus the Younger against his brother, Artaxerxes II, King of Persia. The term “Anabasis,” meaning a march inland, is appropriate for the first six chapters, which narrate the advance of Cyrus’s army up to Cunaxa, near Babylon.

The narrative then details the decisive Battle of Cunaxa, in which Cyrus is killed, the assassination of the key Greek generals by Tissaphernes, the desperate situation of the mercenaries, the election of new generals (one of whom is Xenophon), their retreat to the Black Sea, and their subsequent adventures in Asia Minor until the survivors join the Spartan army of Thibron, who was in the region to fight Tissaphernes.

Anabasis is a unique historical composition that combines characteristics of military memoirs, travel descriptions, and biographies. From the third book onwards, the events are largely presented from Xenophon’s perspective, who plays such a significant role that in the later books, the story essentially takes the form of a biography. Notably, the frequency of Xenophon’s presence as a character is inversely proportional to that of the narrator.

Thus, first-person narrative interventions are less frequent compared to Hellenica and tend to decrease as the historical narrative progresses and the character of Xenophon becomes more prominent. It seems that Xenophon’s favorable portrayal as a character led him to adopt an impersonal and more detached manner of expression. Unlike his contemporaries, who appear as characters in their historical works and always refer to themselves in the third person, Xenophon even attributes the authorship of Anabasis to a certain Themistogenes of Syracuse in Hellenica.

This gesture, which previously led to speculation that Anabasis might have been published under the pseudonym Themistogenes of Syracuse, should be seen as a rhetorical move by Xenophon to shield himself from accusations of self-promotion and to lend his work greater objectivity.

Like Hellenica, Anabasis possesses significant literary qualities. The narrative is lively and, despite containing various geographical and ethnographic details, is distinguished by exemplary economy, as Xenophon remains focused on conveying events and generally avoids extensive digressions from his main objective. However, speeches are frequent, reflecting the personalities of the speakers and complementing their characterization inferred from the narrative.

Xenophon’s literary skill is particularly evident in the description of individual episodes; for instance, the legendary scene where the Greeks finally see the sea (4.7). It is also worth mentioning that this work revisits the favorite theme of the art of governance, but now the didactic goal is realized not so much by the narrator as by the character of Xenophon, whom readers see evolving into a mature and accomplished leader, very different from the impulsive young man who once ignored Socrates’ reasonable concern.

Agesilaus

A biographical encomium of the Spartan king Agesilaus II, whom Xenophon greatly admired. The work highlights Agesilaus’s virtues, leadership qualities, and military successes. It serves as both a tribute and a model of an ideal ruler, reflecting Xenophon’s respect and close relationship with the Spartan king.

Memorabilia

Divided into four books, this work defends Socrates against the accusations of corrupting the youth and impiety. It presents Socratic dialogues and reminiscences, showcasing Socrates’ philosophical teachings and moral character. Xenophon aims to restore Socrates’ reputation and demonstrate his commitment to ethical values.

Apology of Socrates

This work provides a different perspective on Socrates’ defense compared to Plato’s Apology. It emphasizes Socrates’ wisdom and ethical principles during his trial. The authenticity of this work is disputed, but it offers insight into how Socrates’ followers perceived his trial and condemnation.

Symposium

Describes a banquet hosted by the wealthy Callias to celebrate the victory of the young Autolycus at the Panathenaic Games. During the symposium, Socrates and other guests engage in philosophical discussions on topics such as love, pleasure, wealth, and beauty. The work provides a lively portrayal of Socratic dialogue in a social setting.

Oeconomicus

A Socratic dialogue focusing on household management and agriculture. Ischomachus, a wealthy landowner, discusses with Socrates how he organizes his estate and trains his young wife in domestic duties. The work is practical and instructional, reflecting Xenophon’s interest in rural life and efficient management.

Hiero or Tyrannicus

A political dialogue between Hiero, the tyrant of Syracuse, and the poet Simonides. Simonides advises Hiero on making his tyranny more bearable for both the people and himself. The work explores themes of power, governance, and the moral implications of tyranny.

Cyropaedia

A partly fictional biography of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Persian Empire. Divided into eight books, it covers Cyrus’s education, military campaigns, and administrative practices. The work blends historical facts with idealized portrayals, presenting Cyrus as a model ruler who embodies both practical wisdom and ethical virtues.

Constitution of the Lacedaemonians

Describes the political and military systems of Sparta. Xenophon praises the laws and institutions established by Lycurgus, crediting them with Sparta’s strength and stability. The work reflects Xenophon’s admiration for Spartan discipline and societal organization.

Ways and Means

A treatise on the economic conditions of Athens, proposing methods for economic and social reconstruction. Xenophon suggests practical measures to increase revenue and improve the city’s financial stability, reflecting his concern for Athens’ prosperity and sustainability.

On Hunting

Advocates hunting as an excellent educational tool and a means of physical and moral training. The work provides practical advice on hunting techniques and extols the virtues of this activity as a divine invention.

On Horsemanship

Offers detailed instructions on horse care and training for cavalrymen. Xenophon’s expertise in horsemanship is evident as he provides practical advice on selecting, grooming, and managing horses, emphasizing the importance of proper treatment and training.

Hipparchicus

Describes the duties of the hipparch (cavalry commander). The work outlines the responsibilities and strategies for effective cavalry leadership, reflecting Xenophon’s military experience and knowledge.