Who was Aesop

According to one version, he was sent by Croesus with offerings of gifts to the temple of Apollo at Delphi, where, seeing the frauds of the priests there and their greed, he accused them in a sarcastic manner.

They, then, decided to kill him by treachery. So they took a golden flask from the sanctuary of the temple and hid it in his luggage. Then they accused him of being a thief and a heretic. So with the staged accusation they condemned him to death and killed him by throwing him over the cliff from the top of Parnassus, Yambeia. Immediately after his death, famine and misery fell upon the land.

According to another version, Aesop was a slave of a landowner who used him as a shepherd. One day, when he saw the overseer unfairly beating another slave, he ran to help him, so the overseer, in order to take revenge, accused him of the landowner, who took him to the market of Ephesus to sell him.

There, he was bought by the wise Xanthos from Samos, who appreciated his intelligent look and took him with him as a slave. With him she started traveling and getting to know the world. Xanthos then sold him to the Samian sage Iadmons. Appreciating his spiritual gifts and above all his wisdom and intelligence, he released him.

Once, when some dared to mock him for his ugliness, they received the following answer: “Do not pay attention to a man’s appearance, but his mind.”

When he was young, he was sold as a slave to a landowner and later to a passing slave trader. He took him to Ephesus and brought him to the market to sell.

Xanthos, a Samian philosopher, passed by the market, and bought him, because he found him at a cheap price, and because from the conversation he had with him, he appeared to him to be an intelligent man. It is said that he then sold it to the Samian philosopher Iadmons as well.

In the house of Iadmon, Aesop told his fables to his master’s children to entertain them, and whenever he wished to advise or teach them he did not say directly what he wanted, but made up a fable.

However, Aesop did not remain a slave for long. He was “released” because he gave a correct interpretation to an omen. The Samians now had him with them and consulted him on all their difficult cases.

That Aesop was a real person is confirmed by Herodotus, who lived a few years in Samos and who, writing for some other person.

In the work of Herodotus Alcarnissios Histories, Logoi IX, Inscribed Musai accidentally also mentions Aesop. According to information derived from this testimony, Aesop was a contemporary of the poetess Sappho and the Seven Wise Men of ancient Greece.

When Aesop was at Samos, Croesus, king of Lydia, having made war, subdued almost the whole region of Phrygia and imposed taxes. He wanted to impose taxes on the Samians as well.

Aesop as an envoy of the Samians visited Croesus and there he spoke with so much wit and wisdom that he managed to get him not to ask for the taxes he demanded and to become their friend. Thus Samos was liberated.

After a while he returned to Samos, where he was received with great honor and gratitude.

From Samos he began his travels to various countries, studying the customs and traditions of various peoples and philosophizing.

The greatest storyteller of antiquity was Aesop, a slave who formulated in a satirical style fables that had a symbolic character.

Herodotus described him as a “reasoner”, while Plutarch described him as an ugly slave, who stammered and had crooked legs. However, he was insightful and created a series of allegories that are still popular with young children. Many versions have been put forward about his life.

The most popular states that he was born in 625 BC. in Amoria in Phrygia from a family of slaves and was engaged in cultivating the land and tending the animals on behalf of his master.

However, he did not remain long in the employ of his first master. He sold him in a slave market in Ephesus and was bought by Xanthos of Samos, a philosopher, who valued him and took him with him on his travels in the then known world.

Aesop had the opportunity to see animals such as lions, observe the animal kingdom, and write fables with central characters the lazy cicada, the industrious ant, the greedy dog, and the sly fox. His fables were short stories with animals that spoke and acted like people and concluded with a moral lesson.

At some point Aesop arrived at Delphi and met the priests of the oracle, whom he did not value and considered to be deceiving the faithful. In fact, he accused them of being greedy and using the tools to make money.

The priests reacted to the accusation and claimed that he had stolen a holy cup and sentenced him to death and threw him off a cliff of Parnassus.

Despite the fact that he was a slave, the Athenians appreciated his work and built Hadrian in his honor. Although Aesop did not write the fables, but told them orally, most survived by word of mouth.

Demetrius Falireus was the first to publish some myths in the 4th century BC. During the Middle Ages, other collections were released, which became popular and made Aesop known in all countries of the world.

[ez-toc]

The fables of Aesop

These fables often feature anthropomorphic animals or inanimate objects that act and speak like humans, presenting moral lessons or conveying simple truths about human nature and behavior.

These are small domestic narratives, formulated with great brevity. Their character is didactic, symbolic and allegorical. These Myths have a special grace, wonderful simplicity and unfathomable teaching.

They are taken from everyday life and nature. He had the unique ability to give animals human qualities, soul and speech, to such an extent that you believe that his fables were once reality and all that he narrates has happened. A key feature of his stories was the epimythium which was understandable for children and the people.

Aesop’s Fables (Aesopou’s Fables) were written in prose. As is well known, until then, only metered speech, poetry, was considered the only expressive genre for writers. Therefore, it can also be considered as a pioneer in its kind. Their ideology is the rejection of evil in its most representative forms: violence, fraud, arbitrariness, betrayal, vanity, arrogance, falsehood, greed, cunning.

The disapproval is attempted sometimes by reference to the Divine judgment, sometimes by persuasive suggestions, but more often by establishing the absurdity of evil, by ridiculing it as well as by the philosophical contemplation of life.

According to Herodotus, Aesop was a well-known “rhetoricist”[8]. Besides fables, he knew and told many jokes and anecdotes. Others argue that he did not create myths but collected them, completed them and perfected them.

They came either from the most ancient Greeks or from other peoples, such as the Phrygians. Of course, it is possible that he invented some of them himself. However, he used them a lot in his life, with such skill and success that his name was eventually associated with them.

It is said that he told these myths not only during his lifetime but also in order to support his innocence in court. In them, his broad, observant spirit and his ability to teach with small, simple stories, which always have a moral lesson at the end, can be distinguished.

Aesop used with his observation and deep wisdom to fashion such stories and tell them around him. In time he gained a great reputation and everyone ran to him to hear some of his fables about some of their problems. Little by little his myths began to be transmitted by word of mouth among the people, until the Hellenistic era when they were collected for the first time.

The Fox and the Grapes fable

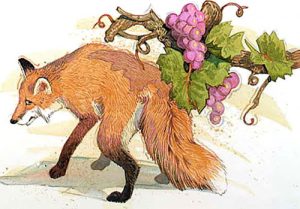

Excited by the sight of the grapes, the fox’s mouth began to water, and he immediately desired to taste them. He leaped up, trying to reach the grapes, but they were hanging just out of his reach. Undeterred, the fox backed up, took a running start, and made another leap, but the grapes remained elusive.

The fox tried several more times, jumping with all his might, but each time he fell short. Exhausted and frustrated, the fox finally gave up, sitting down at a distance, panting heavily. Disappointed, he muttered to himself, “Those grapes are probably sour anyway. I’m sure they’re not worth the effort.”

And with that, the fox turned his back on the grapes, pretending not to care anymore. He walked away, trying to convince himself that he didn’t want them after all.

The moral of the fable is that sometimes people tend to belittle or reject things they desire but cannot obtain. In this story, the fox, unable to reach the grapes, tries to console himself by claiming they are sour and not worth his effort. The fable highlights how individuals often rationalize their failures or disappointments by diminishing the value of what they desire but cannot attain.

The Boy Who Cried Wolf fable

So, the boy climbed up a small hill, where he could see the entire village, and shouted at the top of his lungs, “Wolf! Wolf! The wolf is attacking the sheep!” The villagers, alarmed by the cries, dropped whatever they were doing and rushed towards the hill, carrying sticks and pitchforks, ready to defend the sheep.

But when they reached the top of the hill, all they found was the boy, laughing mischievously. “Ha! There was no wolf,” he exclaimed, delighting in his prank. The villagers were annoyed but forgave him, warning him not to cry wolf when there was no danger.

Days passed, and the boy grew bored with his routine duties. Remembering the excitement his prank had caused, he decided to do it again. Climbing up the hill, he shouted, “Wolf! Wolf! Please help, the wolf is attacking the sheep!” Once more, the villagers, concerned for the safety of the flock, dropped everything and rushed up the hill. And once again, they found the boy grinning, reveling in the chaos he had created.

The villagers were furious this time. “You foolish boy! We won’t fall for your tricks again,” they scolded him, shaking their heads in disappointment. They left, muttering about how he needed to learn a lesson about honesty.

Weeks passed, and the boy’s pranks were forgotten. One sunny day, as the boy watched over the grazing sheep, a genuine sense of fear washed over him. He saw a large, menacing wolf approaching the flock. Terrified, he called out as loud as he could, “Wolf! Wolf! Help! The wolf is really attacking the sheep this time!”

But this time, the villagers ignored his cries. They had grown tired of his lies and believed he was playing another prank. They continued with their tasks, paying no heed to his desperate calls for help. The wolf lunged at the sheep, snatching one after another until the flock was decimated.

the boy realized his foolishness and the consequences of his actions. He had lied too many times, and now no one believed him, even when he spoke the truth. His heart sank as he witnessed the devastation caused by his earlier deceit.

From that day on, the boy learned the importance of honesty and the consequences of lying. The once playful boy became a responsible shepherd, always truthful and trustworthy. And as for the villagers, they learned a valuable lesson as well—to distinguish between genuine calls for help and deceitful cries, for sometimes, actions have consequences that cannot be undone

The Lion and the Mouse fable

Meanwhile, a small mouse happened to be passing by. Curiosity piqued, the mouse cautiously approached the source of the commotion. As it saw the trapped lion, the mouse’s heart filled with sympathy. Despite its size, the mouse resolved to help the mighty lion escape from the hunter’s net.

Approaching the lion, the mouse asked, “Do not fear, mighty lion. I shall gnaw through these ropes and set you free.”

The lion, struggling to free itself, couldn’t help but chuckle at the mouse’s proclamation. However, it didn’t dismiss the mouse’s offer, realizing that any help was better than none. With a nod, the lion agreed.

The small mouse scurried around the net, gnawing and biting at the ropes with all its might. Slowly but surely, the tiny creature managed to cut through the net, setting the lion free. The relieved lion stretched its powerful limbs, gratitude shining in its eyes.

“Thank you, little mouse,” the lion exclaimed. “You have saved my life, despite my initial doubts.”

The mouse humbly replied, “It was nothing, mighty lion. We should help each other, no matter our size or strength.”

The lion, now humbled by the mouse’s act of kindness, realized the truth in the small creature’s words. From that day forward, the lion vowed to show compassion and mercy to all the animals of the forest, regardless of their size or power.

Time went by, and word of the lion’s change of heart spread throughout the animal kingdom. The animals, no longer living in constant fear, approached the lion with their problems, seeking its wise counsel and protection. The lion became known as a fair and just ruler, earning the respect and loyalty of its subjects.

And as for the small mouse, it lived happily in the forest, knowing that even the mightiest of creatures could be grateful for the help of the smallest and humblest of beings. The fable of “The Lion and the Mouse” served as a timeless reminder that acts of kindness, no matter how small, can have a significant impact and create a bond of friendship between unlikely allies.

The ant and the grasshopper fable

As summer approached, the ant began to gather food and store it in its anthill. The grasshopper, on the other hand, continued to sing and dance, not paying any attention to the approaching change in seasons.

When winter arrived, the meadow was covered in a thick blanket of snow. The grasshopper, who hadn’t made any preparations, found itself hungry and shivering in the cold. It realized that it had been foolish not to think about the future and its needs.

Desperate and hungry, the grasshopper went to the ant’s anthill and humbly asked for some food. The ant, who had worked hard all summer, had plenty of food stored away. But it was not pleased with the grasshopper’s laziness and lack of foresight.

“Why should I give you food when you spent all summer singing and dancing instead of preparing?” the ant scolded.

The grasshopper, feeling regretful, pleaded for forgiveness and promised to change its ways. It admitted its mistake and asked for a chance to work and contribute.

The wise ant, considering the grasshopper’s sincerity, decided to give it a lesson. It offered the grasshopper some food but told it to work alongside the ants in the spring and summer, gathering food for the next winter.

From that day on, the grasshopper realized the importance of hard work and planning for the future. It diligently worked side by side with the ants, learning the value of preparedness and responsibility.

The moral of this fable is that it is wise to plan for the future and work hard in the present. Neglecting responsibilities and indulging in laziness can lead to difficulties and regret later on.

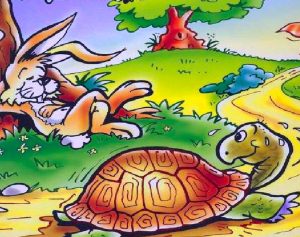

The Tortoise and the Hare fable

One sunny day, the Hare spotted the Tortoise slowly making his way through the meadow. With a mischievous gleam in his eye, the Hare decided to mock the Tortoise. “Why are you so slow?” the Hare asked, chuckling. “You’ll never get anywhere at this pace!”

The Tortoise, unaffected by the Hare’s taunting, replied calmly, “Slow and steady wins the race, my friend. We’ll see who reaches the finish line first.”

Amused by the Tortoise’s confidence, the Hare proposed a race. He was certain he would win, so he agreed to the challenge without hesitation. The other animals in the meadow gathered around, eager to witness the spectacle.

On the day of the race, the Tortoise and the Hare stood side by side at the starting line. The Hare’s supporters cheered him on, confident of his victory, while the Tortoise’s friends encouraged him to do his best.

With a signal from the crow acting as the race official, the race began. The Hare sprinted off like lightning, leaving the Tortoise far behind. The crowd gasped in awe at the Hare’s speed, convinced that the race was already over.

Meanwhile, the Tortoise maintained his slow and steady pace, undeterred by the Hare’s impressive lead. He focused on putting one foot in front of the other, determined to stay true to his nature.

As the Hare ran ahead, he grew overconfident. He thought he had so much time to spare that he could afford to take a nap before reaching the finish line. So, he found a comfortable spot under a shady tree and dozed off, confident of his victory.

While the Hare slept, the Tortoise continued to plod along. He passed by the slumbering Hare, his progress unnoticed by the dozing speedster. The Tortoise’s slow and steady pace allowed him to make steady progress, step by step, while the Hare snoozed away.

Finally, the Tortoise approached the finish line. The crowd erupted in cheers and applause, astonished by the Tortoise’s unexpected progress. Just as he crossed the finish line, the Hare woke up, realizing with a start that he had fallen asleep.

Rushing to the finish line, the Hare was shocked to see the Tortoise already there, basking in the glory of his victory. The Hare felt a deep sense of regret and embarrassment, realizing that he had underestimated his opponent.

The moral of the fable of “The Tortoise and the Hare” is that slow and steady progress, combined with determination and perseverance, can often overcome swift but careless speed. It teaches us to avoid overconfidence and to appreciate the value of consistency and focus in achieving our goals.

Edition of Aeop’s fables

A selection of Aesop’s fables in prose was published by Dimitrios Falireus at the end of the 4th century BC. This collection is not preserved and only poetic elaborations by Bavrius in Greek, Phaedrus in Latin and others, saved the material of that epitome. All extant collections are much later and date from the 1st or 2nd century onwards. His fables have been collected in “Collection of Aesopian Fables”.

They were first printed in Milan in 1479 AD, in Venice in 1525 and 1543 by the family of printers Damiano di Santa Maria followed by an edition in Paris in 1547.

Adamantios Korais printed them in 1810 in Paris followed by a critical edition in 1852 in Leipzig from Halm. Since then many editions have appeared and the Myths are believed to have been read worldwide almost as much as the Bible.

Their most recent edition was by the British publishing house Penguin (1997) in 50,000 copies. Their translation into the modern Greek language was made by Andronikos Noukios and Georgios Aitolos, who lived in the 16th century.