History of the Ancient Greek theatre

The theatre in ancient Greece stands as a monumental achievement in the history of Western civilization, shaping the foundations of drama and performance art as we understand them today. Originating in the 6th century BCE, Greek theatre evolved from religious festivals and rituals dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and ecstasy, into a sophisticated form of artistic expression that explored the depths of human nature, politics, and society.

The theatre in ancient Greece stands as a monumental achievement in the history of Western civilization, shaping the foundations of drama and performance art as we understand them today. Originating in the 6th century BCE, Greek theatre evolved from religious festivals and rituals dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and ecstasy, into a sophisticated form of artistic expression that explored the depths of human nature, politics, and society.

The legacy of ancient Greek theatre is profound, influencing the development of Western drama, literature, and performance art. The structural elements, themes, and narrative techniques pioneered by Greek playwrights have been adopted, adapted, and reinterpreted through the centuries, resonating with audiences across different cultures and epochs. Moreover, the philosophical and ethical questions raised by Greek tragedies and comedies continue to provoke reflection on the human condition, morality, and society.

Origins and Development

The origins and development of Greek theatre are deeply rooted in the religious and cultural practices of ancient Greece, reflecting a journey from ritualistic ceremonies to a sophisticated art form that has profoundly influenced Western dramatic tradition.

The genesis of Greek theatre can be traced back to the 6th century BCE, with its origins linked to the worship of Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and ecstasy. The earliest form of Greek drama was the dithyramb, a choral hymn sung and danced in honor of Dionysus. These performances, featuring a chorus of men or boys, were part of the Dionysian festivals, particularly the City Dionysia in Athens, which became a significant cultural event drawing participants and spectators from across the Greek world.

As the dithyramb evolved, it laid the groundwork for the development of Greek theatre. A key innovation attributed to Thespis, a poet and performer of the 6th century BCE, was the introduction of the actor (hypokrites), who interacted with the chorus, effectively creating a dialogue and paving the way for dramatic narrative. This innovation is so significant that Thespis is often considered the “father of tragedy,” and it is from his name that we derive the term “thespian” to describe actors.

Over time, the structure of Greek drama became more complex, with the addition of more actors, the development of distinct genres like tragedy and comedy, and the creation of written scripts that explored a wide range of human experiences and emotions. The 5th century BCE, known as the Golden Age of Athens, saw the emergence of the great tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, whose works delved into themes of fate, morality, and the divine, often through the lens of mythological and historical tales. Aeschylus is credited with adding a second actor to the performance, expanding the potential for dramatic interaction, while Sophocles introduced a third actor and scene painting, further enhancing the theatrical experience.

Comedy also flourished during this period, with Aristophanes being the most famous comic playwright. His plays, characterized by satirical and often bawdy humor, critiqued contemporary Athenian society, politics, and culture.

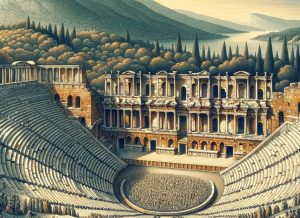

The physical space for these performances also evolved, with the construction of open-air theatres (theatrons) built into hillsides, featuring a circular dancing floor (orchestra), an altar to Dionysus, and tiered seating for spectators. The most iconic of these is the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, which became the model for subsequent Greek and Roman theatres.

The influence of Greek theatre extended beyond its immediate cultural and temporal context, with Roman theatre adopting and adapting Greek dramatic forms. Greek tragedies and comedies were preserved and studied by scholars throughout the ages, inspiring Renaissance playwrights and continuing to influence modern drama. The legacy of Greek theatre, with its exploration of universal themes and its innovations in performance and storytelling, remains a cornerstone of Western literature and the performing arts.

Architectural Innovation

Greek theatre was characterized by its distinctive architecture, designed to accommodate large audiences and to enhance acoustic performance. Theatres were built into hillsides, utilizing the natural slope to create a tiered seating area known as the theatron. At the heart of the theatre was the orchestra, a circular space where the chorus performed, which was adjacent to the skene, a structure that served as both a backdrop for the action and a dressing room for actors. This architectural layout facilitated a communal viewing experience, where the audience could engage with the performance in an immersive environment.

Genres of Drama: Tragedy and Comedy

Greek theatre gave birth to two major genres of drama: tragedy and comedy. Tragedy explored profound themes such as fate, moral integrity, and the gods’ influence over human affairs, often through the tragic downfall of a noble protagonist.

Greek theatre gave birth to two major genres of drama: tragedy and comedy. Tragedy explored profound themes such as fate, moral integrity, and the gods’ influence over human affairs, often through the tragic downfall of a noble protagonist.

Early tragedies were composed by playwrights like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, whose works, including “Oedipus Rex,” “Antigone,” and “Medea,” remain cornerstones of literary study.

The genres of drama, particularly tragedy and comedy, represent two fundamental aspects of the human experience, capturing the spectrum of emotions, conflicts, and societal norms that define our existence.

Tragedy

Tragedy, one of the oldest forms of drama, delves deep into the darker side of human nature, exploring themes of suffering, loss, and the inexorable consequences of human actions. Originating in ancient Greece, tragedies were often tied to myths and historical events, focusing on characters of high status whose downfall was brought about by a combination of fatal flaws (hamartia), fate, and the will of the gods.

This genre is characterized by its serious tone and profound moral and philosophical questioning. Tragedies aim to evoke a sense of catharsis, a purification or purging of emotions, allowing the audience to experience pity and fear and, through this emotional release, gain insights into the complexities of life and the human condition. Notable playwrights such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides crafted masterpieces like “Oedipus Rex” and “Medea” that epitomize the tragic form, highlighting the inevitable clash between individual aspirations and the harsh realities of the world.

Comedy

Comedy, in contrast, embraces the lighter side of life, using humor, satire, and irony to entertain and critique society. Unlike tragedy, which focuses on noble characters and their fall from grace, comedy often revolves around ordinary people and their foibles, misadventures, and the pursuit of happiness, usually resulting in a happy or at least a reconciliatory ending. The origins of comedy can also be traced back to ancient Greece, with Aristophanes and Menander among its earliest practitioners. This genre has evolved over the centuries, encompassing various sub-genres such as farce, romantic comedy, and satirical comedy, each employing different methods to elicit laughter and provoke thought. Comedies serve not only to amuse but also to reflect societal norms, criticize political and social issues, and, ultimately, to reveal truths about human nature and the absurdities of life.

Both tragedy and comedy, through their distinct approaches, offer valuable insights into the human psyche, social structures, and the existential dilemmas that have captivated audiences from ancient times to the present day. They underscore the complexity of human life, the myriad ways in which we navigate our existence, and the enduring power of drama to connect us to the broader tapestry of human experience.

The Role of the Chorus

The chorus played a central role in Greek theatre, serving as a collective character that provided background information, commentary, and reflections on the events of the play. The chorus’s lyrical odes and dances bridged the scenes of the drama, creating a rhythm that structured the performance and engaged the audience emotionally and intellectually.

The chorus in ancient Greek theatre played a significant role and had multiple functions, serving as a key component of Greek drama, particularly in the works of playwrights like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides during the 5th century BCE. Its roles and functions can be summarized as follows:

The chorus often provided background information that was necessary for understanding the context of the story. They could narrate events that had happened before the play’s action began or explain offstage events that were important to the plot.

The chorus often represented the voice of the average citizen or the societal norms of the time. They would comment on the actions of the characters and the moral dilemmas presented in the play, reflecting the ethical concerns and the collective conscience of the community.

Through their odes and songs, the chorus would heighten the emotional atmosphere of the play and react to events in the story, amplifying the emotional response of the audience. Their lyrical expressions helped to create a deeper emotional connection with the audience.

The chorus could also play a role in the development of the plot. Their interactions with the characters could drive the narrative forward, pose questions, offer advice, or challenge actions, influencing the direction of the story.

The chorus’s songs and odes provided a break in the action, offering the audience a moment to reflect on the events of the play. This structural role helped to pace the drama and divide it into sections.

The chorus added a musical dimension to the theatre, performing choral odes accompanied by music and dance. This aspect of their role added to the aesthetic appeal and the spectacle of the performance.

In early Greek theatre, the chorus had a religious significance, as performances were part of religious festivals dedicated to gods like Dionysus. The chorus’s participation was a way to honor the gods and integrate the spiritual with the theatrical.

The size and specific role of the chorus varied from play to play and evolved over time, from the large choruses of early Greek tragedy to smaller groups in later works. Despite these variations, the chorus remained an essential element of Greek theatre, providing a multifaceted function that enriched the dramatic experience for ancient audiences.

Cultural and Religious Significance

Theatre in ancient Greece was deeply intertwined with the cultural and religious life of the city-state. Major theatrical performances were held during religious festivals, such as the City Dionysia in Athens, which celebrated Dionysus through dramatic competitions. These festivals not only showcased the latest works of drama but also served as a communal experience that reinforced social cohesion and civic identity.

Its inception, closely tied to the worship of Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and revelry, underscores the theatre’s sacred origins. Dramatic performances, initially part of Dionysian festivals, served both as acts of homage and as communal rituals, fostering a shared religious experience among participants and spectators.

The evolution of Greek theatre from simple choral performances to sophisticated dramas written by playwrights like Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes, marked a significant cultural development. These dramas, encompassing tragedy and comedy, explored themes of human existence, morality, and the divine, offering audiences profound insights into the human condition and the complexities of the gods. Through these narratives, the theatre became a mirror reflecting societal values, beliefs, and concerns, making it an essential instrument for social commentary and critique.

Moreover, the architectural design of ancient Greek theatres, built into hillsides with a natural amphitheater layout, emphasized the importance of community and collective engagement. The structure facilitated a shared auditory and visual experience, symbolizing the unity of the polis (city-state) and reinforcing the communal aspects of Greek culture. This design also highlighted the democratic ethos of ancient Greece, as citizens from various social strata gathered to watch and participate in the theatrical events.

The performance of plays during significant festivals, such as the City Dionysia in Athens, further illustrates the theatre’s integral role in civic and religious life. These festivals, attended by citizens and foreigners alike, promoted civic identity and pride while also serving as occasions for religious observance and homage to the gods. The competitive nature of these festivals, where playwrights and actors vied for accolades, underscored the cultural value placed on artistic excellence and innovation.

In conclusion, the ancient Greek theatre was much more than a venue for entertainment; it was a vital expression of cultural identity, religious devotion, and communal unity. Through its integration of dramatic art, architecture, and festival, the theatre encapsulated the spiritual, intellectual, and social ethos of ancient Greece, leaving a lasting legacy that continues to influence Western culture and thought.

Greek theatre’s architectural principles

Greek theatre’s architectural principles reflect a remarkable blend of aesthetic, functional, and symbolic considerations, designed to facilitate dramatic performances and to accommodate large audiences in an open-air setting. These principles not only served the practical needs of ancient performances but also embodied the cultural and religious significance of theatre in Greek society. Key aspects of Greek theatre architecture include its layout, acoustics, and integration with the natural landscape, all of which contributed to the immersive experience of ancient drama.

Integration with Natural Landscape

Greek theatres were typically built into the slopes of hills or mountains, taking advantage of the natural topography to create a tiered seating area, known as the “theatron.” This not only provided ample seating with clear lines of sight for spectators but also enhanced the acoustics, allowing the voices of actors and chorus members to project throughout the space. The natural setting also contributed to the aesthetic and spiritual experience of the audience, connecting the drama with the broader cosmos and the gods.

The Theatron

The theatron was the main seating area, consisting of concentric rows of benches that curved around the orchestra, the central performance space. This arrangement fostered a sense of community among the audience members, as they shared the collective experience of the performance. The semi-circular shape of the theatron ensured that spectators had an unobstructed view of the stage and the chorus, making every seat a good seat.

The Orchestra

At the heart of the Greek theatre was the orchestra, a circular or semi-circular area where the chorus performed dances and songs integral to the drama. Positioned at the base of the theatron and in front of the skene, the orchestra was the focal point of the theatre, where much of the action took place. Its design facilitated the chorus’s movements and interactions with the actors, enhancing the visual and emotional impact of the performance.

The Skene

The skene was a building situated behind the orchestra, serving multiple purposes. Initially, it functioned as a dressing room for actors and storage for props and equipment. Over time, the skene evolved to become a backdrop for the action, with painted panels and movable scenery that depicted various settings, from palaces to temples. The skene also included a raised platform, or “proskenion,” which extended the performance space and allowed for more complex staging and visual effects.

Acoustics

Greek theatre architects demonstrated an advanced understanding of acoustics, designing theatres that amplified sound naturally. The open-air amphitheaters, with their curved seating and the use of hard materials like stone, helped project the actors’ and chorus’s voices throughout the space, ensuring that even spectators seated far from the orchestra could hear the performance clearly. This acoustic efficiency was critical in a time before electronic amplification, allowing for the nuanced delivery of dialogue, music, and choral odes.

Symbolic Elements

Beyond their functional aspects, Greek theatres also held symbolic significance, reflecting the societal and religious importance of theatrical performances. The open connection between the performance space and the sky above symbolized the presence of the gods, who were believed to be watching the dramas unfold. The orientation of the theatre, often facing the rising sun, further reinforced the connection between the divine, nature, and human activity.