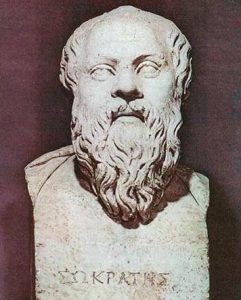

Socrates, the greatest Philosopher of Ancient Greece (c.470-399 BC)

Socrates was one of the greatest philosophers of Greece, known to us through his pupil Plato, the historian Xenophon and other ancient sources. Other famous pupils and/or friends of his were Aristippus and Antisthenes, and he influenced Romans like Seneca and Marcus Aurelius.

Socrates was one of the greatest philosophers of Greece, known to us through his pupil Plato, the historian Xenophon and other ancient sources. Other famous pupils and/or friends of his were Aristippus and Antisthenes, and he influenced Romans like Seneca and Marcus Aurelius.

Socrates was born in Athens , son of a sculptor, Sophroniscus, and a midwife, Phaenarete. He was educated in literature, music and gymn-astics and also rhetorics, dialectics and sophism. He is described as short and ugly, looking like Silenus, and he himself would make jokes about his appearance. His wife was the angry Xanthippe.

We know very little about his childhood and youth and about the education and upbringing he received, which should not have been different from that of the middle-class children of the craftsmen of Athens: reading and writing, learning Homeric epics, music , gymnastics.

In the Platonic dialogue of Phaedon, which takes place in prison, when Socrates talks for the last time with his friends and students just before drinking hemp, the condemned philosopher describes how, already young, he began to watch the penetration of various philosophical theories in Athens: the young Socrates began to deal with natural philosophy and, above all, with Anaxagoras’ theory of the Mind.

As Socrates himself never wrote anything, what we learn either about his life or his philosophical theories, we learn from the texts of his students, mainly Plato, but also Xenophon. Socrates is the main figure in all of Plato’s dialogues, except the Laws. In fact, some dialogues, Euthyphron, Critias and Faidon, works that are placed before the trial the first and after the condemnation the other two, especially the Apology (a work that is supposed to reproduce as faithfully as possible what Socrates actually said in his apology) offer us important information about the life of the philosopher. An apology was also written by Xenophon, who also offers us news about the life and views of Socrates in his works Memoirs, Symposium and Economics.

As Socrates himself never wrote anything, what we learn either about his life or his philosophical theories, we learn from the texts of his students, mainly Plato, but also Xenophon. Socrates is the main figure in all of Plato’s dialogues, except the Laws. In fact, some dialogues, Euthyphron, Critias and Faidon, works that are placed before the trial the first and after the condemnation the other two, especially the Apology (a work that is supposed to reproduce as faithfully as possible what Socrates actually said in his apology) offer us important information about the life of the philosopher. An apology was also written by Xenophon, who also offers us news about the life and views of Socrates in his works Memoirs, Symposium and Economics.

Another source, clearly unreliable in terms of the ideas and interests that Socrates quickly presented, but very brilliant for the comic presentation of man himself, is Aristophanes. In the comedy of Nefelae (423 BC) the comedian poet brings Socrates on stage to run a philosophical school, a Tutoring Center: perched on a basket hanging from the roof of the school, the philosopher observes the sun, while below his students study how the flea jumps and where do the insects make sounds! This picture is completely wrong, since Socrates never asked to attract students for a fee and never dealt with natural phenomena.

We know several things about Socrates’ public life. He took part as a hoplite in the battles of Potidaea (431), Delion (424) and Amphipolis (422). These were, after all, the only times that the philosopher traveled outside the borders of Attica, as he says in the Platonic dialogue of Critias.

We also know that Socrates took certain political positions and even at very critical moments in Athenian history. In 406, after the destruction of the Athenian fleet in the naval battle of Arginousa, Socrates presided, as a member of the corps of rectors, in the assembly of the enraged municipality that wanted to sentence to death the generals of the naval battle, who, due to heavy sea manages to collect the corpses of the dead and the shipwrecked.

As rector (in fact, according to some testimonies, he was the caretaker, ie president, of the rectors) he fought the death sentence, which he considered unjust and illegal. This attitude was neither easy nor without dangers in an era of fanaticism and defeatism, during which the people of Athens were desperately looking for scapegoats.

With the same vigor with which he opposed a decision of democracy, Socrates resisted the arbitrariness of the Thirty Tyrants a few years later. As the Thirty Tyrants tried to systematically force as many Athenians as possible to become complicit in their violence and crimes, they ordered Socrates, along with four other citizens, to arrest a citizen, Leo of Salamis, in order to execute him. Socrates categorically refused to participate in the operation. According to Xenophon, his old student Kritias, one of the Thirty, had proposed some measures in order to silence the teacher who did not mean to close his mouth in front of the strong ones. But what the tyrants failed to do, unfortunately, the restored, moderate democracy finally achieved.

If we only know these events of his life, we know enough about the way of life of this strange and provocative man, who, without ever writing a single line of his thoughts, indelibly marked the thought and philosophy of humanity. We know that Socrates was ugly and that, with his flat nose, his round eyes, his thick lips and his wide face, he resembled, as Alcibiades says, the leader of the Satyrs, Silinos. But the words of this man also sounded like the words of Silinos from a satirical drama. And yet, Alcibiades concludes, “if you penetrate into them, then you will understand that only these have meaning, that they are divine words” (Symposium).

The fact that Socrates’ words had something divine was not only acknowledged by Alcibiades, nor only by the young and ambitious young men of Athens who left their teachers and ran after him, but was also acknowledged by Apollo of Delphi. Hairefon, a friend of Socrates, went to the oracle of Delphi and asked the God to indicate the wisest man. And Apollo replied that Socrates is Always the wisest. Wise, the man who provocatively proclaimed “I only know that I know nothing”

The fact that Socrates’ words had something divine was not only acknowledged by Alcibiades, nor only by the young and ambitious young men of Athens who left their teachers and ran after him, but was also acknowledged by Apollo of Delphi. Hairefon, a friend of Socrates, went to the oracle of Delphi and asked the God to indicate the wisest man. And Apollo replied that Socrates is Always the wisest. Wise, the man who provocatively proclaimed “I only know that I know nothing”

Before becoming known as a philosopher he worked as a sculptor, and was wealthy enough to have a house of his own and money lent out in return for a favourable interest. At the age of about 40 he served in the infantry of the Athenian army during the Peloponnesian War. After the oracle in Delphi had said he was the wisest man in the world, Socrates spent the rest of his life as a speaker and teacher.

His famous quote “I only know that I know nothing” very much reflects his views. He believed he was ignorant as well as people in general, and he tried to help them understand this through dialogues where he asked questions and let the subject through his own answers come to realizasion of whatever the matter was. To him, man was born good, but ignorance makes his actions bad sometimes. The only true virtue is knowledge. Through argumentation and definitions of ethical ideas one could get on the right path. “Know thyself”, he said.

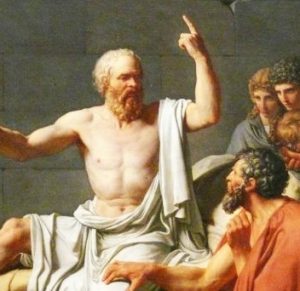

Socrates dispute

Socrates was not an atheist, but he was an irony and made irony a weapon of thought, a weapon of search and philosophical research. Maybe in question he really looked like a sophist. And they refused to take for granted the admitted truths. But their challenge ended in denial: since no one can discover the truth, there is no truth, and if there is, it does not matter, because it does not affect us. In the face of this challenge, which quickly ends in tragedy but also monster, Socrates confronts a positive challenge: by challenging traditional ideas and traditional principles, he seeks the deeper truth of things. Much more, he seeks the first truth, the unchanging, which is not affected by conditions, which does not depend on man.

Socrates was not an atheist, but he was an irony and made irony a weapon of thought, a weapon of search and philosophical research. Maybe in question he really looked like a sophist. And they refused to take for granted the admitted truths. But their challenge ended in denial: since no one can discover the truth, there is no truth, and if there is, it does not matter, because it does not affect us. In the face of this challenge, which quickly ends in tragedy but also monster, Socrates confronts a positive challenge: by challenging traditional ideas and traditional principles, he seeks the deeper truth of things. Much more, he seeks the first truth, the unchanging, which is not affected by conditions, which does not depend on man.

Dialectical and obstetric method

His weapons were dialectical and obstetric. As he describes in the excerpt from the Apology, Socrates used the dialectic as a means of controlling and drawing conclusions, which in principle means dialogue. Of course, this is not any discussion. The Socratic dialectic is the gradual, step-by-step, undoing of the interlocutor’s positions and then the also gradual attempt to draw a new conclusion, a new approach to truth. In the Platonic dialogues, Socrates’ interlocutor first sets out a view of the subject to be discussed, which he considers complete and well-founded.

With questions that seem almost simplistic, Socrates forces his interlocutor to reach the extreme consistency of the positions he supported and there proves the fragility of the logical arguments he used. From this point a new discussion begins, where again, guiding his interlocutor with questions, Socrates leads him to the general truth, to the truth that exists regardless of the circumstances and circumstances, to the first truth of things.

It is characteristic that Socrates, in the Platonic dialogues, does not decide himself in advance, he does not quote a theory or point of view from the beginning. On the contrary, all the intellectual effort of the debate is focused on extracting the Socratic point of view from the opponent. This is what Socrates himself called obstetrics.

Obstetrics, of course, is the job of the midwife, the midwife who supports and helps the pregnant woman in childbirth. Taking as an example the work of his mother, who was a midwife, Socrates claimed that he never “gave birth” to a philosophical theory by himself, but doing that as a midwife, helps his interlocutor to “give birth” to the truth from within. But what does this mean? It means that for Socrates every man knows the truth, the Idea, and that the effort of philosophical thought is to help him to remember it, to bring it back to his memory.

The search for definitions, the inductive method and ethics

It has been said of Socrates that he “brought philosophy down from the stars to the earth”, in the sense that, thanks to his own personality, philosophers ceased to deal so much with natural phenomena (which have since become the object of science rather than philosophy ), as much as with man himself and his society. The truth is that the earlier philosophers also dealt with political problems, while Democritus and many sophists also dealt with ethical issues. Socrates, however, is the one who turned his philosophical thinking exclusively to such matters.

The reason that Socratic interests marked the history of philosophy in such an indelible way must be sought in the Socratic way of thinking, that is, in the fact that Socrates was not merely interested in the right way of life and action either personally or socially.

Unlike the sophists, whose interest in these matters was utterly utilitarian, Socrates sought a stable ground on which to define strictly and irrevocably every notion of goodness, virtue, and wisdom. As the first philosophers sought the first principle of creation, Socrates sought the principle of every moral concept, which is not influenced by historical and social conditions nor by the possibility of perception of every human being. In other words, he sought the absolute by rejecting the relevant, the essence of ethics and not the moral phenomena.

The path that Socrates logically followed to seek precisely the absolute essence of moral concepts, was the inductive method , with the aim exporting universal definitions (not rooting at all). In other words, starting from examples, usually taken from everyday life and experience, he tried to lead the thought of his interlocutor to draw universal conclusions, which go beyond experience and reach an absolute knowledge of the subject.

This process was successful when an absolute definition, that is, an absolute knowledge of the truth of good and evil, of injustice and justice, of beauty and ugliness, of wisdom and dementia, of courage and cowardice, finally emerged. , good governance and domination. Thus, the man who claimed that the only thing he knows is his own ignorance, definitively marked the course of philosophy by pointing out that rational thought and not the senses is the only guide to truth, to the universal and the eternal.

The trial and death of Socrates

Althought well-known, Socrates was not popular with everybody. Aristophanes satirized him, the Sophist were his opponents and many believed he had a hand in the aristocratic revolt of 404 BC, which for a short time interrupted the democracy.

Althought well-known, Socrates was not popular with everybody. Aristophanes satirized him, the Sophist were his opponents and many believed he had a hand in the aristocratic revolt of 404 BC, which for a short time interrupted the democracy.

The lawsuit against Socrates was made by Melitos, a poet whose only glory is the fact that he was an accuser of the philosopher. Anytos and Lykon were also accusers. The first was a rich tanner and well-known politician, who had been elected general in 409 and had been exiled by the Thirty Tyrants. The second was an orator.

Why was Socrates sued? Obviously not because the accusers really believed that Socrates did not believe in the gods or because they were really bothered by the famous demon, the deity who, as Socrates said, lived inside him and advised him. The ancient Greek religion had neither a holy book nor a dogma (hence neither sects) nor a priesthood with a special mission of mediation between gods and men.

Priests and priestesses were usually elected for a certain period by some citizens, in exactly the same way as they were elected in the other offices of the city (with the exception of a few specific cults, such as the Eleusinian mysteries, where certain families traditionally performed priestly duties). It was therefore almost impossible to accuse anyone of atheism, since he even participated in the major common religious ceremonies and did not question them.

The usual accusation leveled at some intellectuals was disrespect, that is, precisely non-participation or, worse, undermining the value of these ceremonies.

Anaxagoras and Protagoras, but also Aeschylus, the tragic poet, had probably been tried for such accusations. As in these cases, so in the case of Socrates, religion was the pretext behind which the political reasons for the persecution were hidden.

The accusation of youth corruption had more to do with the real cause of Socrates’ persecution. Socrates certainly did not corrupt the young people who followed him. But, as he says in his Plato Αpology, the young who saw him exposing the false wisdom of the sophists and demagogues in the market were fascinated by this “game” that led to the search for the essence of things and the truth.

And, of course, those threatened by Socrates and his annoying questions, considered the philosopher’s fascination to the youth to be “corruption.” But there is another important element: many of the young people who belonged to the circle of Socrates took an active part in politics and played a negative role in a time catastrophic for Athens.

Alcibiades, first of all, was α democrat, but also extremely controversial, since he did not hesitate to defect to the Spartans.

Many friends of Socrates, on the other hand, sided with the extreme oligarchs and supported the coup of the Thirty Tyrants. Kritias and Harmidis, in fact, uncles of Plato, were among their leaders. This allowed his accusers to imply that the teacher’s theories were responsible for the conclusion of his “students”.

The People’s Court of Ilia, consisting of 500 judges drawn from all the older citizens, found Socrates guilty by a moderate majority (281 votes against 220). In the second ballot, the death sentence was passed by a majority (300 vs. 201).

The irony of Socrates is not unrelated to this development: when he was given the floor in order, according to the law, to propose a sentence, Socrates, instead of proposing e.g. exile, proposed his contempt for both the court and death:

“What suits a poor man and benefactor of the city, who needs free time to urge you for good? Nothing suits him better than putting him in the rectory and feeding him for free… So if I have to propose something worthy of me, I propose to be honored with food at the rectory.” [Plato’s Apology].

Explaining then why a man at his age has no reason to fear death, he proposes, for formal (and ironic) reasons, the fine of a mna (Dracma). This amount was increased to 30 mna. Plato, Kriton and other friends, came as guarantors, since the property of Socrates did not exceed 5 mna.

After his conviction, Socrates remained in custody for about a month. In those days they took place on the sacred island of Apollo, Delos, the Delia fest. The Athenians had sent there a theory (official mission in a sacred ceremony) representatives of the city and one of their two sacred ships, the Paralos. According to the custom, execution could not take place until the return of the ship. During his imprisonment, and until the last moment, Socrates said to the Athenians: “And now our paths part- I go to Death while you go to Life. Who goes to the better only God knows.”

Although offered help to escape by his friends and pupils Socrates decided against it, talking about how the citizen must obey the laws and decisions of the authorities. After having said goodbye to his wife and children, and having some conversations about the immortality of the soul with his friends and disciples, Socrates finally drank the poison that a guard had given him.