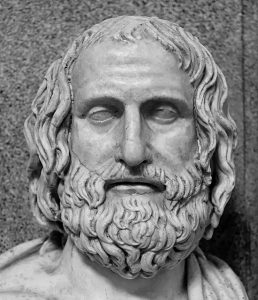

Euripides and his works

Euripides, son of Mnesarchus, was born in Salamis but originated from Phlya (Chalandri). His love for the sea decisively marked his work. He devoted himself to athletics and music and engaged in painting and philosophy.

Euripides, son of Mnesarchus, was born in Salamis but originated from Phlya (Chalandri). His love for the sea decisively marked his work. He devoted himself to athletics and music and engaged in painting and philosophy.

He lived during a time shaped by the Peloponnesian War, the work of the sophists, and generally new ideas and concerns, which are inherent in his work and reflect intellectual disputes. Open to the influence of the intellectual climate of Athens, he nonetheless maintained the independence of his spirit, often expressing criticism. His literary career was intense.

His new art caused a great stir and did not receive the audience’s approval. Thus, throughout his life, while participating in the dramatic competitions for about fifty years, he was declared first only four times. His first performance, with which he won the third prize, took place in 455 BC, three years after the performance of Aeschylus’s Oresteia.

An antisocial type—having few friends—, introverted, melancholic, and inaccessible, he completely abstained from the political and social events of his era, actively participating only in the intellectual movement of enlightenment and forming close relationships with the sophists (especially Protagoras), Anaxagoras, Socrates, etc.

At the end of his life, he sought refuge in the court of King Archelaus of Macedonia in Pella, where he died in 406 BC. Sophocles, in the proagon of the Great Dionysia that year, himself in mourning attire, presented the Chorus and actors without crowns, due to the death of Euripides, causing the audience to weep.

His persona was associated with abundant anecdotal lore, demeaning to him, which was inspired by comic poets, particularly Aristophanes. However, the legendary misogyny attributed to him is not true; on the contrary, the poet was sensitive to the marginalization of women in his era’s society.

Innovation in Tragedy

Euripides is often regarded as a revolutionary figure in the realm of Greek tragedy. He pushed the boundaries of the traditional structure of tragic plays by introducing complex characters who displayed a wide range of emotions and motivations. His focus on the internal struggles and moral dilemmas faced by his characters added a new dimension to Greek drama, making his plays more relatable to audiences both in his own time and in the centuries that followed. Euripides’ willingness to explore themes such as the folly of war, the oppression of women, and the flaws of gods and heroes was groundbreaking and laid the foundation for modern character-driven storytelling.

Psychological Depth

One of Euripides’ most significant contributions to drama is his exploration of psychological complexity. His characters are often depicted as multifaceted individuals caught in the web of their desires, fears, and societal constraints. For instance, in “Medea,” he presents a protagonist who is both a sympathetic victim and a ruthless avenger, offering a nuanced portrayal of a woman driven to the edge by betrayal and loss. This psychological depth invites audiences to empathize with characters’ plights, understand their motivations, and reflect on the nature of human behavior.

Challenging Societal Norms

Euripides was known for his critical examination of the social, political, and religious norms of Athenian society. Through his plays, he questioned the justice of the gods, the ethics of war, and the treatment of women and foreigners. “The Trojan Women” serves as a poignant critique of the dehumanization and suffering caused by war, particularly on the lives of women and children. By giving voice to those marginalized by society, Euripides highlighted the injustices and hypocrisy of the prevailing social order, encouraging his audience to reconsider their values and beliefs.

Lasting Influence

The legacy of Euripides extends far beyond the ancient Greek world. His works have been translated, adapted, and performed across different cultures and epochs, resonating with audiences for their universal themes and emotional depth. In the Renaissance, his tragedies inspired new forms of drama and literature, while in the modern era, his exploration of individual psychology and social critique has influenced playwrights, novelists, and filmmakers.

Euripides’ impact is also evident in the realm of philosophy and psychology, where his insights into human nature and the complexities of the psyche have been studied and admired. The existential questions and moral ambiguities that permeate his plays continue to provoke debate and reflection, underscoring the timeless relevance of his work.

The works of Euripides

Euripides is credited with 92 works. Today, 18 tragedies (the authenticity of one of them, Rhesus, is disputed) and one satyr play (Cyclops) survive. Additionally, 117 fragments of his works have been preserved. The dates of some tragedies are approximate. Specifically:

Euripides wrote works with a political orientation and included scenes reflecting the problems of his time. The experience of the Peloponnesian War and the atmosphere of disillusionment it created marked the poet and his work. Patriotism and a peace-loving spirit, combined with the promotion of Athens’s past and Athenian magnanimity, characterize several of his tragedies.

Heracleidae (circa 430 BC)

The tragedy “Heracleidae” (also known as “The Children of Heracles”) by Euripides is a compelling exploration of themes such as asylum, justice, and the legacy of heroism set against the backdrop of ancient Greek mythology and history. Written in approximately 430 BCE, this play focuses on the plight of the children of Heracles (Hercules in Roman mythology), who are fleeing from Eurystheus, the king of Argos, who seeks to kill them due to a prophecy and his enmity with Heracles.

The narrative begins with the children of Heracles, along with their grandmother Alcmene and Heracles’ nephew Iolaus, seeking refuge in Athens. They implore the Athenian king, Demophon, for protection against Eurystheus, who is pursuing them to fulfill an oracle that prophesied his death at the hands of a descendant of Heracles. Demophon, faced with the moral and political dilemma of protecting the suppliants at the risk of war with Argos, consults the oracle of Apollo to determine the best course of action. The oracle commands that Athens must protect the children of Heracles, but a noble Athenian must be sacrificed to ensure victory.

The play delves into the themes of loyalty, sacrifice, and the responsibilities of leadership as Demophon grapples with the oracle’s demand. In a striking turn of events, a volunteer emerges for the sacrifice, demonstrating the themes of selflessness and heroism that permeate the play.

“Heracleidae” is notable for its focus on the concept of asylum and the protection of the innocent, as well as the exploration of Athenian ideals of democracy and justice. Euripides uses the mythological narrative to comment on contemporary political and social issues, particularly Athens’ role as a protector of the oppressed and a beacon of civilization.

The resolution of the play involves divine intervention and the fulfillment of the prophecy concerning Eurystheus, showcasing the interplay between human agency and fate—a common theme in Greek tragedies. “Heracleidae” offers a nuanced perspective on the legacy of Heracles, not through his own deeds, but through the actions of his descendants and their protectors, reflecting on the enduring impact of heroism across generations.

Hecuba (426 or 424 BC)

“Hecuba” is a powerful tragedy by the ancient Greek playwright Euripides, believed to have been written around 424 BCE. The play is set in the aftermath of the Trojan War and centers on the fallen queen of Troy, Hecuba, who has been reduced to slavery. The narrative explores themes of revenge, suffering, and the transformation of grief into a desire for justice, offering a profound commentary on the human condition and the cycles of violence that can emerge from profound loss.

The tragedy unfolds in the Thracian camp where the Greek ships are anchored, waiting for favorable winds to return home after the fall of Troy. Hecuba, once a queen, now finds herself a slave, grappling with the enormity of her losses, including her city, her husband King Priam, and most of her children. The play begins with the ghost of Hecuba’s son Polydorus, who reveals that he was sent to Thrace for safety and entrusted to the king Polymestor along with gold. However, after Troy’s fall, Polymestor murders Polydorus to seize the gold.

The plot thickens when Hecuba learns that her daughter Polyxena has been chosen as a human sacrifice to honor the grave of Achilles, further compounding her grief. Hecuba’s sorrow at these revelations sets the stage for a narrative driven by her quest for justice and revenge.

The play is divided into two main parts: the first deals with the sacrifice of Polyxena, and the second with Hecuba’s revenge on Polymestor for the murder of Polydorus. Polyxena’s sacrifice is depicted as an act of noble self-sacrifice, earning her praise from both the Trojans and Greeks for her courage and dignity in facing death. In stark contrast, the second part of the play focuses on Hecuba’s cunning plan to exact revenge on Polymestor for his betrayal and the murder of Polydorus. Hecuba’s transformation from a grieving mother to an avenger highlights the play’s exploration of the depths of despair and the potential for vengeance that lies within the human heart.

“Hecuba” is a tragedy that delves into the darkest aspects of human experience, questioning the nature of justice and the morality of revenge. Through the character of Hecuba, Euripides presents a portrait of human suffering and resilience, making the play a timeless exploration of the tragedies of war and the enduring spirit of those who survive its horrors.

Trojan Women (415 BC)

“The Trojan Women” by Euripides is a profound and harrowing tragedy that delves deep into the aftermath of the Trojan War, portraying the suffering and despair of the women left in the ruins of Troy. Written in 415 BCE, amidst the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, this play serves as a poignant commentary on the atrocities of war and its devastating effects on the innocent, particularly women and children. Euripides uses the backdrop of the legendary fall of Troy to explore themes of loss, grief, and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable adversity.

The play is set in the aftermath of Troy’s destruction, with the once proud city now in ruins and its male population slaughtered. The Trojan women, including Queen Hecuba, her daughters Cassandra and Andromache, and Helen of Troy, await their fates at the hands of the victorious Greek soldiers who plan to divide them as spoils of war. The narrative focuses on their lamentations, fears, and the cruel destinies that await them—slavery, rape, and separation from their homeland.

One by one, the fates of the main characters are revealed: Cassandra is destined to become the concubine of Agamemnon, despite her prophetic warnings of doom; Andromache is to be taken by Neoptolemus, and her young son Astyanax is brutally killed to prevent him from seeking revenge for Troy’s fall in the future; Helen faces a trial for her role in sparking the war, although she argues her case to return to Greece with Menelaus.

“The Trojan Women” is notable for its stark portrayal of the consequences of war, stripped of glory and honor, focusing instead on the suffering and degradation of the victims. Euripides criticizes the brutality and senselessness of war, challenging the audience to reflect on the morality and justice of their own actions in conflict. The play is a powerful indictment of the inhumanity of war and a timeless reminder of the price paid by the innocent when empires clash and fall. Through the voices of the Trojan women, Euripides conveys a message of empathy and compassion that transcends the ages, making “The Trojan Women” one of the most enduring and emotionally resonant works in the canon of ancient Greek drama.

Medea (431 BC)

Jason, son of Pelias, king of Iolcus, after the Argonautic expedition, takes as his wife the sorceress Medea, daughter of Aeetes from Colchis, who assisted him in the capture of the Golden Fleece. Driven away by Pelias, they seek refuge in Corinth, where King Creon grants them asylum.

In this tragedy, we witness the drama of a woman who is abandoned (deserted) and driven by the passion for revenge. Her erotic frenzy leads her to a monstrous act: she causes the death of her young rival, Glauce, daughter of Creon who was to marry Jason, and then, after wavering and psychological shifts, slaughters her own children. To escape Jason’s vengeance, she flees in a chariot pulled by winged dragons of the Sun to Athens, where King Aegeus hosts her.

The Chorus, consisting of Corinthian women, praises the beauties of Athens and lauds its intellectual values, wondering at the same time how such a polis would accept the heinous murderess.

Hippolytus (428 BC)

The core of the work is the passion of a woman: Phaedra, by design of Aphrodite, falls madly in love with Hippolytus, son of her husband Theseus and the Amazon Hippolyta. When her secret is betrayed, she decides to die and drags the young man into destruction, who confronted her love with abhorrence. Just before hanging herself, she leaves a letter for her husband, accusing Hippolytus of dishonoring her. Theseus is enraged, curses his son, and a heated dialogue follows between them. Hippolytus departs distressed. A messenger announces to Theseus that his son is dying because a raging bull, sent by Poseidon, overturned his chariot. Artemis reveals to Theseus the purity and innocence of Hippolytus. Theseus mourns and seeks forgiveness.

The characters of Euripides act according to a clearly defined ideal and confront fears and desires. They are characters willing to sacrifice themselves for their loved ones and their country. However, the poet does not only depict passions and sacrifices but also often characters who are far from heroic.

Alcestis (438 BC)

he work highlights the noble sacrifice of Alcestis, wife of Admetus, king of the Phereans of Thessaly, who wholeheartedly agrees to die instead of her husband after the refusal of Pheres to sacrifice himself in place of his son. Alcestis bids farewell to worldly life with emotion and dies in front of the spectators. Hercules, wrestling with Death, brings the heroine back from the Underworld.

The tragedy also presents weak, cowardly characters. The heroine’s husband, Admetus, and especially her father, Pheres, are characters filled with selfishness and hardly heroic. Father and son exchange accusations of cowardice, while the idealized figure of the young Alcestis, who fulfills her duty, is highlighted.

Phoenician Women (409-408 BC)

The Phoenician Women” (Phoinissai) by Euripides is a complex tragedy that delves into the themes of power, family conflict, and destiny within the context of Theban mythology. Believed to have been written around 408 BCE, the play is named after the chorus of Phoenician women who are on their way to Delphi but find themselves caught in the midst of the Theban conflict. The narrative intertwines various threads of the Theban saga, focusing on the curse of Oedipus and its devastating impact on his sons, Eteocles and Polynices, who are embroiled in a deadly struggle for control of Thebes.

The backdrop of the play is the bitter conflict between the two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, following their father Oedipus’s curse. After Oedipus’s self-imposed exile for his unwitting crimes of patricide and incest, the brothers agree to alternate rule over Thebes. However, Eteocles refuses to relinquish power after his term, leading Polynices to amass an army in Argos to reclaim his right. This sets the stage for the impending battle at the seven gates of Thebes, which fulfills the tragic prophecy of their mutual destruction.

Amidst this familial strife, the play also gives attention to their mother, Jocasta, who attempts to mediate between her sons in a bid to prevent the impending catastrophe. Her efforts, however, are in vain, underscoring the theme of inescapable fate that pervades the narrative. The play also features the figure of Antigone, the sister of the feuding brothers, who demonstrates her loyalty and sense of duty towards her family, foreshadowing her own tragic story that is famously explored in another of Sophocles’ plays.

“The Phoenician Women” is unique among Euripides’ works for its extensive exploration of the Theban legends and its ensemble of characters from the mythological saga. The play is characterized by its intricate plot, moral complexity, and the exploration of themes such as the abuse of power, the bonds of family, and the tragic consequences of hubris and inflexibility. Euripides masterfully portrays the human dimension of these mythological figures, making their struggles and dilemmas resonate with universal themes of human existence.

Although not as frequently staged or studied as Euripides’ other works, “The Phoenician Women” stands as a rich and layered tragedy that offers a profound commentary on the destructive nature of power struggles and the inexorable pull of fate, making it a significant contribution to the corpus of ancient Greek drama.

Iphigenia in Aulis (406 BC, performed posthumously)

Agamemnon calls his daughter Iphigenia to Aulis under the pretext of marrying her to Achilles. In reality, he intends to sacrifice her to the goddess Artemis to invoke favorable winds for the Greek ships to sail to Troy. However, the leaders hesitate before the sacrifice, and Achilles is enraged. Iphigenia, realizing that the Greek expedition is not a personal matter but a collective one, offers the heroic solution: she proceeds undaunted to death for the salvation of Greece.

The unexpected, conflicts between deception and revelation, misunderstanding, and theatrical reversal dominate three of the poet’s works, intrigue plays that more closely resemble romantic fiction.

Ion (418/417 BC)

The tragedy “Ion” by Euripides is a fascinating work that blends elements of mystery, divine intervention, and the complexities of human emotion within the context of ancient Greek mythology. Written in the late 5th century BCE, “Ion” explores themes of identity, family, and the intertwining of human lives with the will of the gods.

The play opens at the temple of Apollo in Delphi, where we meet the central character, Ion, a young orphan who serves as a temple assistant. Unbeknownst to him, Ion is the son of Apollo and Creusa, the daughter of Erechtheus, a former king of Athens. Creusa had abandoned Ion at birth because he was the result of a rape by Apollo. She later married Xuthus, who is childless and seeking an oracle about his lack of offspring.

The plot thickens as the oracle deceitfully tells Xuthus that the first person he meets upon leaving the temple will be his son, who turns out to be Ion. This revelation leads to a series of misunderstandings and emotional turmoil, as Creusa and Ion are unaware of their true relationship to each other.

In her despair, Creusa attempts to kill Ion, thinking him a threat to her legitimate heirs, but the plot is thwarted. It is only through divine intervention and the revealing of hidden tokens that Ion and Creusa finally recognize their blood relation. The play concludes with Apollo’s messenger explaining the misunderstandings and declaring that Ion will be honored in Athens as the ancestor of a noble line, while Creusa and Xuthus accept him as their son.

“Ion” is unique among Euripides’ plays for its relatively happy ending and the way it handles complex issues of legitimacy, divine will, and human agency. The play raises questions about the nature of family and the role of the gods in human lives, making it a rich text for exploration in the context of ancient Greek drama.

Iphigenia among the Taurians (413-412 BC)

Iphigenia, serving as a priestess of Artemis in the land of the Taurians in Crimea after her miraculous salvation in Aulis, accidentally recognizes that the foreigner she must sacrifice, according to local customs, is her brother Orestes. Orestes went to this country with Pylades, according to an oracle of Apollo, to be freed from the madness caused by matricide and with the command to transfer to Attica the xoanon (= wooden statue < ξέω) of the goddess. The danger of a horrific murder adds tragedy to the work.

The theft of the xoanon from the temple is achieved by trickery, but the ruler of the country, Thoas, chases the two siblings. Athena’s intervention (“deus ex machina”) halts the pursuit. Thoas obeys the goddess and promises to execute her orders (the siblings’ salvation, the liberation of the Greek women of the Chorus).

Helen (412 BC)

According to the poet’s adapted version of the well-known myth, Helen never went to Troy, and the gods gave Paris first and then Menelaus an image of her. The real Helen is in Egypt, where Menelaus arrives shipwrecked. The recognition of the spouses occurs when Helen was forced to yield to the country’s king, Theoclymenus, who wants to marry her, and Menelaus is at risk of being killed. A scene of deception is inserted, and the spouses escape. Enraged, the king pursues the fugitives, but the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux), Helen’s brothers, “as deus ex machina,” convince him to accept the will of the gods.

The figure of the beautiful Helen embodies perfect beauty and erotic passion but also symbolizes the divine curse that causes destruction to the Greek and Trojan people. The myth of Helen inspired creators in all eras. In antiquity, poets and prose writers dealt with the theme and outlined her character: Homer (Iliad and Odyssey), Alcaeus, Stesichorus (“Palinode”), Aeschylus (Agamemnon), Euripides (Trojan Women, Helen), Gorgias (Encomium of Helen), Isocrates, Theocritus. In modern poetry, the myth is addressed by G. Seferis (“…for an empty shirt, for a Helen…”), G. Ritsos, O. Elytis, A. Sikelianos, T. Sinopoulos, and in European poetry by R. de Ronsard, G. Apollinaire, P.J. Jouve, Th. de Banville, etc.

In Euripides’ theater, there are unpleasant and pleasant surprises, reversals for the worse and for the better. Reversals for the worse are more naturally attributed to the gods. However, Euripides refers to the gods when he wants to indicate the factors of instability and deception contained in human fate.

Heracles (417 BC)

The hero returns triumphant from his descent into Hades and saves his wife Megara and their children from the hostile fury of Lykos, the usurper of the Theban royal throne. Subsequently, however, he is seized by madness (“Madness” is the other title), caused on behalf of Hera by Lyssa, and kills his own, whom he just saved (reversal). Assistance to Heracles, who contemplates suicide when he realizes his act, will ultimately come not from the gods but from Theseus, the representative of human solidarity. Together they head to Athens to purify Heracles from the pollution.

The poet-philosopher (called “philosopher from the stage” for the philosophical views of his work) deals with themes already presented in the theater by Aeschylus and Sophocles (e.g., matricide, punishment of hubris). However, he presents them differently, in a realistic manner.

Electra (417, possibly 413 BC)

Euripides’ “Electra,” composed in the late 5th century BC, offers a distinctive interpretation of the well-trodden mythological narrative concerning the aftermath of King Agamemnon’s murder. Unlike the renditions by his contemporaries Aeschylus and Sophocles, Euripides situates his version of the story in a setting that starkly contrasts with the royal splendor typically associated with Greek tragedy, opting instead for a more grounded and psychologically nuanced exploration of vengeance, justice, and familial loyalty.

Set in the rural outskirts of Argos, Euripides introduces us to an Electra stripped of her royal status and forced into a life of destitution, married off to a humble farmer by Clytemnestra and Aegisthus in an effort to thwart any potential revenge. This setting serves as a backdrop for Euripides’ exploration of themes such as the corrupting influence of power, the complexities of human emotion, and the moral ambiguities surrounding the act of vengeance.

Electra’s character is rendered with depth and complexity, oscillating between despair, resilience, and unyielding desire for retribution against her father’s murderers. Her interactions with her estranged brother Orestes, who returns in disguise to execute their plan of vengeance, provide a poignant exploration of duty, familial bonds, and the psychological toll of their blood-stained legacy.

Euripides’ “Electra” diverges from traditional depictions by emphasizing the psychological realism and moral ambiguity of its characters rather than focusing solely on the mechanics of the plot. The play challenges the audience to contemplate the cost of vengeance and the cyclical nature of violence, questioning the very foundations of justice and morality in a world governed by gods and men alike.

Through the use of dramatic irony, tense dialogues, and a chorus that reflects the moral and thematic concerns of the narrative, Euripides crafts a tragedy that resonates with timeless questions about the nature of justice, the complexities of human emotion, and the inescapable shadows cast by our familial obligations. “Electra” stands as a testament to Euripides’ mastery in portraying the eternal struggles of the human condition, making it a compelling and thought-provoking addition to the corpus of Greek tragedy.

Orestes (408 BC)

Euripides’ ‘Orestes,’ penned in 408 BC, remains a pivotal work in the canon of ancient Greek tragedy, showcasing the playwright’s adeptness at blending psychological depth with intricate plot development. The play unfolds in the aftermath of Orestes’ matricide, the killing of his mother Clytemnestra to avenge the murder of his father, Agamemnon. This act plunges Orestes into a vortex of guilt, madness, and divine retribution, reflecting Euripides’ fascination with the human psyche and the consequences of actions driven by the pursuit of justice and honor.

Set against the backdrop of Argos, the drama explores themes of vengeance, justice, familial loyalty, and the search for redemption in a world governed by capricious gods. Orestes, alongside his sister Electra, finds himself ensnared in a relentless cycle of bloodshed, struggling to navigate the murky waters of moral ambiguity and societal expectations. Their plight is compounded by political machinations and the fickleness of allies, underscoring the fragility of human relationships in the face of overarching vendettas.

Euripides’ ‘Orestes’ diverges from traditional portrayals of its titular character, offering a nuanced exploration of his turmoil and the ramifications of his actions not only on his psyche but also on the fabric of Argive society. The introduction of characters such as Menelaus and Helen adds layers of complexity, challenging the audience to reconsider notions of heroism, villainy, and the elusive nature of justice.

Through the employment of a chorus, monologues, and dialogues rich in philosophical and existential inquiry, Euripides invites the audience into a reflective discourse on the human condition, the power of fate, and the divine’s role in mortal affairs. ‘Orestes’ is a testament to Euripides’ mastery in portraying the eternal struggle between the dictates of the gods and human agency, offering insights that resonate with audiences across ages.

Bacchae (406 BC)

“Bacchae,” one of Euripides’ last works, completed shortly before his death in 406 BC and posthumously premiered in Athens, stands as a towering achievement in ancient Greek tragedy, encapsulating the playwright’s profound exploration of human psychology, divine power, and societal norms. This masterpiece diverges from Euripides’ typical focus on humanistic themes, delving deep into the realm of the divine and its intersection with the mortal world, through the story of Dionysus, the god of wine, ecstasy, and revelry, and his return to his birthplace, Thebes, to establish his cult.

The play is a rich tapestry of themes, including identity, vengeance, and the tension between order and chaos, civilization and primordial nature. Dionysus, seeking recognition for his divinity and worship in Thebes, confronts the skeptical and authoritarian King Pentheus, who denies the legitimacy of Dionysus’s divine lineage and seeks to suppress his cult. This conflict sets the stage for a profound exploration of the duality of human nature, the irresistible allure of the irrational and ecstatic, and the catastrophic consequences of denying one’s innate desires and divine truths.

Euripides crafts a narrative that is both a gripping family drama and a theological inquiry, with Dionysus’s dual nature as both god and man serving as a central motif. The god’s ability to inspire both creative liberation and destructive frenzy among his followers, particularly the women of Thebes who abandon their societal roles to become his Bacchae, offers a commentary on the power of the divine to disrupt societal norms and the human psyche.

“Bacchae” is celebrated for its complex characterizations, especially that of Pentheus, whose tragic flaw lies in his hubris and failure to recognize and respect forces beyond his control. The play’s climax, marked by Pentheus’s brutal demise at the hands of his own mother, Agave, under the spell of Dionysian madness, underscores the tragic consequences of resisting the natural order and the divine.

With its haunting choruses, vivid imagery, and profound philosophical undertones, “Bacchae” transcends its ancient origins to speak to universal themes of power, identity, and the eternal struggle between the constraints of society and the wildness of human nature. Euripides, in one of his most enigmatic and enduring works, invites audiences to reflect on the nature of worship, the allure of the unknown, and the perilous journey of self-discovery and acceptance of the divine within and without.

Rhesus (408 BC)

The tragedy “Rhesus,” attributed to Euripides and dated around 408 BC, stands out within the corpus of ancient Greek literature for its distinctive narrative and thematic focus. However, its authorship has been a matter of scholarly debate, with some suggesting it might not have been written by Euripides. Drawing upon the “Iliad” by Homer, specifically the “Doloneia” (Book 10), “Rhesus” delves into a lesser-explored episode of the Trojan War, spotlighting the nocturnal raid that leads to the death of the Thracian king Rhesus.

The play’s title character, Rhesus, arrives as an ally to the Trojans, bringing fresh hope with his formidable horses, prophesied to ensure Troy’s victory should they drink from the Scamander River. However, his untimely death at the hands of Diomedes and Odysseus, Greek warriors, under the cover of darkness, thwarts this prophecy and adds another layer of tragedy to the epic saga of the Trojan War.

Unlike Euripides’ other works, which often focus on psychological depth, moral dilemmas, and the plight of individuals against the backdrop of myth and society, “Rhesus” is characterized by its emphasis on martial valor, the intricacies of warfare strategy, and the fatalistic interplay of prophecy and human action. The tragedy explores themes of heroism, loyalty, and the ephemeral nature of human glory, as well as the impact of divine intervention in the affairs of mortals.

“Rhesus” offers a unique perspective on the Trojan War, providing insights into the valor and strategies of its characters while also reflecting on the broader themes of fate, honor, and the costs of warfare. Its place in the Euripidean oeuvre, whether penned by Euripides himself or another playwright of the time, underscores the richness and diversity of ancient Greek tragedy, inviting audiences and readers to ponder the complexities of heroism and the inexorable march of destiny.

Cyclops (410 BC)

“Cyclops” is a unique and engaging work within the realm of ancient Greek drama, representing Euripides’ sole surviving satyr play and offering a distinct departure from the intense emotional and moral complexities typical of his tragedies. Dated around 410 BC, “Cyclops” delves into the well-known Homeric episode from the “Odyssey,” where Odysseus and his men encounter the monstrous Cyclops Polyphemus on their journey back to Ithaca.

Unlike the solemnity and depth of Euripides’ tragedies, “Cyclops” employs a blend of humor, satire, and irreverence to explore themes of cunning versus brute force, the human condition, and the folly of excessive indulgence. The play features a chorus of satyrs, led by their father Silenus, who, along with Odysseus, become captives of the Cyclops. Their attempts to escape the giant’s cave and the ensuing interactions provide a rich tapestry of comic relief, wit, and moments of tension.

Euripides creatively juxtaposes the bawdy, hedonistic nature of the satyrs with the cunning and resourcefulness of Odysseus, offering a commentary on the diverse aspects of human nature and the virtues of intelligence and strategy over sheer strength. The play also presents a critique of the gods and their capricious involvement in human affairs, a theme recurrent in Euripides’ works but approached here with a lighter touch.

“Cyclops” stands out in the Euripidean corpus for its entertainment value, blending the fantastical elements of myth with the playwright’s keen insights into human behavior and societal norms. This satyr play not only serves as a rare glimpse into a genre that was once a staple of ancient Greek festivals but also as a testament to Euripides’ versatility as a dramatist capable of traversing the spectrum from tragedy to comedy with ease. Through “Cyclops,” audiences are invited to laugh, reflect, and revel in the playful yet poignant exploration of human resilience and ingenuity in the face of daunting challenges.

Characteristics of his poetic art

Euripides, sensitive to the demands of his era, with the atmosphere of disillusionment and bitterness pervasive, presents in his work a world that has nothing in common with the period yearned for by Aeschylus and Sophocles. His heroes are closer to the audience than the heroes of the other tragedians. In his works, he vividly portrays characters, male and female, discusses, protests, condemns, and even subjects the gods to strict criticism. He combines the most painful passion with the most elaborated discussion of the issues that concern him. However, nowhere else do we have such a strong sense that man does not define his destiny as in Euripides’s theater.

A profound investigator of human psychology, “the most tragic of poets,” as Aristotle called him in his Poetics (1453a 30), Euripides marked the tragic genre with profound renewal.

He developed the action with the narrative prologue and epilogue, enhanced the means of impressiveness with the intervention of a supernatural factor for the resolution of the drama’s plot (“deus ex machina”), adapted mythological data to the level of everyday life, He innovated in music, which became more important than speech, and increased the lyrical monodies of the actors, brought his heroes down from their pedestals, presenting them in a realistic manner, according to human measures. He experimented with bold innovations (reduction of choral parts and loose disconnection from the episodes, downgrading the presence of the Chorus as a dramatic organ, free adaptation of myths). His theater, familiar yet bitter, caused surprise and discussions.