Who where the Gods in Greek Mythology

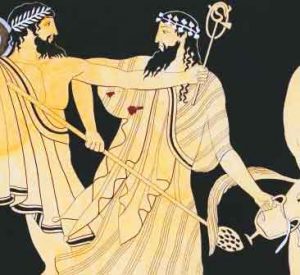

Over the years and with the establishment of the Dionysian cult in the Greek area, Dionysus took the place of Hestia in the Dodecatheon.

Thus the Olympic Pantheon includes all those gods who are honored throughout Greece thanks to the spread of the epics.

The gods belong to the same world as mortals, but they are free from all the negative characteristics that accompany and fill human beings: anguish, weakness, toil, disease, death.

In essence, the gods embody the totality of values, ideals, ideals of human existence, that is, beauty, strength, eternal youth, glorified and brilliant life. The presence or absence of gods in a society determines the fullness of goods, perfection, acceptance or non-moral values such as hospitality.

The Twelve Olympian gods were central figures in the Greek pantheon, residing atop Mount Olympus and playing pivotal roles in numerous myths and legends.

Among the twelve gods, newer researchers distinguish several groups of gods: patriarchal, such as Zeus and Poseidon, young gods, such as Apollo and Hermes, goddesses from an ancient matriarchal tradition, such as Hera and Demeter, and virgin goddesses, such as Athena and Artemis.

Zeus was the undisputed sovereign god. His name links him to the Indian sky god Dyaus pitar and the Roman Diespiter/Jupiter meaning Heavenly Father. At the same time, he was also the god of weather phenomena, whose most characteristic feature was the lightning. He was worshiped under many names including: Yetios, Eleftherios, Hellanios, Diktaios. His wife was Hera, whose name probably means “ripe for marriage”. Hra is characterized by a special relationship with the temple.

Most early temples are dedicated to her (Samos, Argos, Perachora, Olympia). Her competence as the protector of marriage is open to various interpretations depending on the myths and ceremonies of each region.

Poseidon, whose name is usually interpreted as “husband of the earth”, was god of the sea and – as expected – enjoyed particular popularity among the Greeks.

His worship in the Mycenaean Pylos, in the Amphictyonia of Kalaureia, in the Isthmus of the Peloponnese and in Mykali in Ionia was connected with the origin of the oldest Greek races (Iones, Aeolians, Boeotians).

Athena seems to have been named after the city of Athens and not the city after the goddess. This emerges from the Mycenaean tablets, where the “mistress of Athanas” (the Lady of Athens) appears. Goddess of war and protector of citadels and walls, she often bears the epithet Polias and Promachos, while peaceful activities are under the protection of Athena Ergani.

The pre-Homeric name of Apollo was Apellon and was associated with the institution of annual gatherings called apelles. He was the god who expressed the prime of youth and was honored as: Archigetes, Epicurius, Lyceus, Delphinius, Pythius and Musagetis.

As patron of the Muses and god of divination, he simultaneously maintained an ancient destructive dimension, which goes back to Syrophoenician and Hittite patterns.

The sphere of influence of Artemis, Apollo’s sister, covered a wide area from hunting and animals to marriage and childbirth. Her status as Potnia of beasts and goddess of nature connects her with the Asia Minor Cybele.

Aphrodite, the goddess of the pleasant completion of eroticism, owes her origin to the Semitic goddess Ishtar-Astarte. Her Greek name is linked to the myth of her birth in the foam of the sea of Cyprus.

Hermes, messenger god and soul carrier, was the pre-eminent person responsible for transitory situations and movement. Hermas was originally a pile of stones and then a column with a phallic symbol that marked a boundary or a direction. Demeter was – as her name indicates – the mother goddess and the goddess of agriculture and the harvest, without however ever being identified with the earth.

Dionysus, the god of wine and rage, has the name of his father Zeus in the first part of his name. It is thought to have been “imported” from Phrygia or Lydia in the 8th or 7th century BC, but to date this has not been established with certainty. Nor did Phaistos have Greek origins, since a non-Greek population had been preserved in his birthplace of Lemnos until the 6th century BC. He was the god of fire and metallurgy.

Finally, Ares was a god without much popularity. It seems that this is the personification of the adjective “areos”, which in the Iliad is attributed to various gods and means warlike or fighting. Although opponents always remembered him before battles, Ares in only a few places had a temple and enjoyed organized worship.

Goddeses

The goddesses form a multifaceted portrayal of divine femininity in Greek mythology. Each goddess embodies different aspects of the human experience, from wisdom and warfare to love, fertility, and domesticity. Their personalities and stories highlight the interplay between human qualities and natural forces, making them enduring figures in mythology and culture. Through their symbols and narratives, these goddesses convey profound truths about the nature of existence, the cycles of life, and the complexities of human relationships. Their enduring legacy continues to inspire and influence contemporary thought, reflecting the timeless relevance of their mythological roles.

Among the most prominent goddesses is Athena, the goddess of wisdom, war, and craft. Athena’s personality is marked by her intelligence, strategic prowess, and a sense of justice. Unlike Ares, who represents the chaotic and brutal aspects of war, Athena symbolizes strategic warfare and defense. Her symbols include the owl, representing wisdom, and the olive tree, symbolizing peace and prosperity. The Aegis, a protective cloak often depicted with the head of Medusa, is another of her symbols, signifying her role as a protector.

Hera, the queen of the gods and goddess of marriage and family, has a complex personality characterized by both regal dignity and jealousy. As the wife of Zeus, she often finds herself embroiled in conflicts stemming from his numerous infidelities. Despite these turbulent aspects, Hera’s role underscores the sanctity of marriage and the importance of family. Her symbols include the peacock, representing her beauty and pride, and the cow, symbolizing her nurturing aspects.

Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, embodies the power of attraction and the complexities of romantic relationships. Her personality is often seen as both charming and capricious, capable of bringing joy and sorrow. The dove and the rose are her primary symbols, both associated with beauty and the transient nature of love. The sea shell, from which she is said to have emerged, symbolizes birth and fertility.

Demeter, the goddess of the harvest and agriculture, is deeply associated with fertility and the cycle of life and death. Her personality is nurturing and maternal, reflecting her role as the provider of sustenance. The myth of her daughter Persephone’s abduction by Hades and the subsequent changing of the seasons underscores her profound connection to the earth’s fertility cycles. Demeter’s symbols include the cornucopia, representing abundance, and sheaves of wheat, symbolizing the harvest.

Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, wilderness, and childbirth, is characterized by her independence and her protective nature towards women and children. Often depicted as a huntress with a bow and arrows, her symbols include the deer and the cypress tree, representing her association with wild nature. Artemis’s personality embodies both the nurturing aspects of childbirth and the fierce independence of the huntress.

Persephone, the goddess of spring and queen of the underworld, represents the duality of life and death. Her story of abduction by Hades and subsequent return to the earth’s surface for part of the year is symbolic of the seasonal cycle of growth and decay. Persephone’s personality is often seen as reflective and transformative, embodying innocence and maturity. Her symbols include the pomegranate, representing her time in the underworld, and the torch, signifying her role as a guide between worlds.

Hestia, the goddess of the hearth and home, is perhaps the least complex but most essential of the goddesses. Her personality is serene and stable, reflecting the central role of the hearth in maintaining household harmony. Hestia’s symbols are the hearth and the flame, both representing domestic stability and communal well-being.

How the Gods were organised

The gods are organized into a distinct family group, parents, children, siblings, uncles, although the gods of the first generation – Poseidon, Zeus, Hera, Demeter and, according to Hesiod, Aphrodite, are also involved in other relationships.

Zeus and Hera are siblings, Zeus united with Demeter who gave birth to Persephone, Poseidon united with the same goddess and gave birth to the Daughter, whose name is not spoken and is honored with mysterious ceremonies. There are the married couples (Zeus – Hera, Hephaestus – Aphrodite), the erotic (Mars – Aphrodite), the fraternal (Apollo – Artemis), the divine (Poseidon – Demeter), the artisans (Hephaestus – Athena), the single mother ( Demeter) and the virgin goddesses (Artemis – Athena).

For each god a separate genealogical tree is handed down from the sources, with his origin, marriages and descendants, who may be either other deities, major or minor, or heroes, which they acquire from their union with mortals. See, for example, the paintings of the wives and children of Zeus and Poseidon.

Qualities and dual nature of Gods

Many times we find that gods initially have the same qualities and a dual nature, chthonic and marine. For example, the pre-Olympian Poseidon, that is, Poseidon before the division of power, was a dual deity, chthonic and marine, like the father of Uranus and as is evident from the epithets attributed to him and from the tradition that wants him to be the husband of the Earth, co-ruler of Delphi with her, husband of Demeter, but also of sea deities,

Amphitrite and Lefkothea, already known from the signs of Knossos and Pylos. The elements that define Poseidon are also recognized in Zeus the Dodonaeus the Pelasgian, and by extension Olympias, whose chthonic status is revealed in the epithet Meilichios, in which case he is represented as a snake.

We know Aphrodite more as the goddess of love and beauty, but not as the goddess of the dead, with temples among or near the graves of the great cemeteries – in Naxos e.g. they honored the goddess with melancholy sacrifices.

Two traditions exist regarding her birth: one Homeric and the other Hesiodian. According to Homer the goddess of Love is the daughter of Zeus and Dione.

Many times we find that gods initially have the same qualities and a dual nature, chthonic and marine. For example, the pre-Olympian Poseidon, that is, Poseidon before the division of power, was a dual deity, chthonic and marine, like the father of Uranus and as is evident from the epithets attributed to him and from the tradition that wants him to be the husband of the Earth, co-ruler of Delphi with her, husband of Demeter, but also of sea deities, Amphitrite and Lefkothea, already known from the signs of Knossos and Pylos. The elements that define Poseidon are also recognized in Zeus the Dodonaeus the Pelasgian, and by extension Olympias, whose chthonic status is revealed in the epithet Meilichios, in which case he is represented as a snake.

We know Aphrodite more as the goddess of love and beauty, but not as the goddess of the dead, with temples among or near the graves of the great cemeteries – in Naxos e.g. they honored the goddess with melancholy sacrifices.

Two traditions exist regarding her birth: one Homeric and the other Hesiodian. According to Homer the goddess of Love is the daughter of Zeus and Dione.

As Urania and as a goddess with expanded attributes, a Great Mother Goddess, she is represented modestly. As the daughter of Zeus in the Homeric tradition she had to more clearly define her form and consequently limit her power. In Athens the worship of Urania Aphrodite was established by Aegeus, while in Pandimos by Theseus, when he united the municipalities of Attica into one city, an act he did in the name of the worship of Aphrodite: pan-dimos means Aphrodite of all the united Attic municipalities.

Aphrodite as an erotic and unifying force is at the same time a political force, a force that unites individuals in a community and makes them citizens. As Pandemus he is often represented on a ram, which of course requires a mythical etiology. Theseus, following an oracle from Apollo of Delphi, sacrificed a goat in honor of Aphrodite on the beach before setting sail for Crete, to have it as a guide on his journey – let’s not forget Aphrodite’s sea character, since she emerged from the waves. At the time of the sacrifice the goddess transformed into a goat.

However, what we mostly know about Aphrodite Pandimos is the moral, or rather immoral, significance given to her by Plato in the Symposium through the sophist Pausanias. So according to Pausanias of the Platonic Symposium, love is not altogether something noble. Aphrodite Pandimos is love for women, children – as Pentheus describes her to the Bacchus -, she is unstable, just as the beauty of the body is unstable and temporary. On the contrary, Ourania Aphrodite is immutable, eros of the soul, eros male, with characteristics of sensuality and intelligence (Neoplatonism was based on this tradition, as well as Botticelli in The Birth of Aphrodite). In this kind of love Plato recognizes an educational and social role.

According to the English historian R. Osborne, Aphrodite is no more amorous and sensual than other, older clothed figures whose clothes stuck to them, such as the various Nike ( Samothrace, Paionion) or the series of Nereids found in the British Museum . More important was the position the viewer took in front of the statue, the fact that he could move around it (the Cnidians placed it in a round temple), approach it and meet the gaze of the goddess, see the genitals that she hides, to become the unexpected visitor, from whom the goddess tries to hide, or the desired lover. The boundaries between the world of the statue and the world of the viewer become fluid, while the possibilities for an amorous and not just dialectical relationship open up.

To this more speculative approach to the subject, the archaeologist K. Suerev opposes a more religious one. He considers the undressing to be of no small importance and is associated with changes in religious sentiment, and it sparks a series of depictions of the goddess that will culminate in the depiction of a lady ready for copulation or the reactions of a ” lady=”” well-behaved

Minor Greek Gods and Dieties

Of course, there are also deities who, although important, remained secondary or never transcended their local character.

Eileithyia, goddess of childbirth; Asclepius the physician god, Enyalios the war god and Enyo’s consort; Hecate, three-faced, lithe virgin in a short robe, goddess of the night, holding torches, accompanied by barking dogs, present on Persephone’s journey to Hades and from there to earth Prometheus, in whose honor the Prometheus was celebrated in Athens with a torch-lit procession Leto, mother of Apollo and Artemis Thetis, a sea deity accompanied by the Nereids; Leucothea and Eurynome, Mothers and Ladies of the sea-beasts, a Lord of the sea-beasts named Phorcys, Glaucus, Proteus, Nereus, Phorcys; finally, the god Pan, at the limits of civilization and human nature, is worshiped in Arcadia and, since the battle of Marathon and so on, in Attica.

Still other deities are organized into groups according to their gender and age. The youthful forms are considered more important; they are in motion, dancing, singing, frenzy. They are often organized in triads. Instead of gods, they are called demons, servants and precursors, amphipoles and propoles of a goddess or a god, usually one of the great Olympians, such as the Kaveri, the Koryvantes, the Dioscuri, etc.

These groups echo real troupes, as evidenced by the dancing and music. Maenads, Thyades, satyrs in the circle of Dionysus, and male liaisons of Curites in Ephesus are certainly attested in real life. Centaurs refer to actors’ disguises, just as mermaids are primarily disguises. Behind the Kaveri, the Ideal Fingers, the Telchines and the Cyclops are blacksmith guilds. Graces, Muses, Nereids, Oceanids are girls’ dances. Panas and Eileithyia are also given in the plural (apparently the women of the neighborhood who help a woman to give birth).

Poetry describes these groups as members of the world of the gods: Satyrs and Maenads dance around Dionysus, Nymphs surround Artemis, Curites and Koryvantes dance around the newborn Zeus or enthroned Dionysus, the Muses surround Apollo, the Oceanids accompany Persephone to the meadow of her abduction, the Cyclops forge the thunderbolt of Zeus. Titans and Telchines appear as representatives of an ancient age. Finally, some of them are found only in mythology (Titans, Giants), while others enjoy significant worship, such as the Muses, the Graces, the Kaveri.

Several of the deities are forces of nature. The cities honor the rivers and their sources with a special mosque or even a temple. More lively was the worship of the winds and Apollo-Sun. The Moon and Io, goddess of the dawn, also appear in some myths, while the worship of the Earth in the patriarchal religion is particularly limited to echoes in the rifts of the earth. The existence of such deities led to the thought that gods are personifications of natural phenomena. It is true that many times the natural is identified with the divine (Sun, Moon). But the worship of such deities in Greek religion took a backseat to the divine forms established by worship and poetry.

The Immorality of the Gods

Christianity accused the Greek gods of immorality. Indeed, Hermes in the myths appears to steal his own brother, but there are also festivals in which stealing is permitted. Zeus seizes mortal women, but even at feasts the queen will surrender to the strongest. Euphemia goes hand in hand with obscenity, and in fact in respected mysteries such as the Eleusinian, mingling with purification, violence dominates the sacrifices, while human sacrifice is witnessed in the historical sources of the 5th century.

Mythology and ritual are dominated by violence, sexual activity, theft and rapings. The gods themselves clash with each other. Are these all acts of honor? And didn’t the Greeks themselves lie to their gods as early as the 6th century? e.g.; The strange thing is that the most famous temples and the most outstanding statues were made just after this century. Therefore, these are crises that in essence did not touch religion.

It is true that Greek mythology as a whole is erotic, and indeed scandalously erotic if one remains a spectator of individual works of art, outside the context of their finding and functioning. But love implies procreation, which means the affirmation of life against loss, the dissolution of life, death. What mattered in a society where mortality, especially of children, was kept at very high levels, was the preservation of life. After all, Dionysus, the preeminent god of joy, revelry, and love, is also the god of death, and his celebrations have both an erotic and funerary character.

Then, ritually, where theft is part of the action, how unethical can it be in societies like Spartan, where young people from a very early age practice it in preparation for stealing weapons from the enemy? Even the abductions of girls are part of rituals that indicate the social importance of marriage.

As for human sacrifice, we should consider in what cases it was performed and which gods imposed it. In summary here we will mention that human sacrifices are sought by Artemis, protector of the hunt and its rules, when the hunters violate the rules of the hunt and kill animals not out of necessity but as a show and out of arrogant pride (this was, for example, the case of Agamemnon ). Dionysus also imposes human sacrifice in case of refusal of his worship (Minyades, Proitides, women of Thebes). Also, through the human sacrifice of the most elite member of the community, the salvation of the city from unexpected dangers is sought. Heracles’ daughter, i.e. Macaria, offered to sacrifice herself when the oracle said that the victory of the Herakles against Erechtheus would not be possible without a human victim.

Even the case of the medicine could be considered a form of human sacrifice. A pharmaco was a particularly ugly person or with some physical problem, meaning with reduced wholeness and therefore something bad, or an elite member of society. In Athens e.g. two men, especially disliked, were chosen, they were decorated with figs, they were led out as catharsias and apparently they were chased with stones..

In the area of Apollo Lefkata in Lefkada, a criminal was knocked off the rocks, but wings were attached to him to cushion the fall – not active killing but removal over the border, over the rocks, so he wouldn’t come back. The enmity of the community converges on one, whom it expels or kills en masse, often abusing him, since he is held responsible for the unrest and destruction the community suffers. Thanks to this diversion of violence towards a single individual, order and harmony are restored. The outcast is reduced to a savior, to whom the group owes deep gratitude, because through him it is anointed. Medicine therefore becomes for the community a sanctified bastard.

Is a moral order ultimately legitimized through polytheism? The multiplicity of gods also implies oppositions – the disputes between Hera and Zeus, Dionysus and Apollo, Aphrodite and Artemis are well known. Therefore, order can only be understood as respecting the distribution, the shares over which each has jurisdiction. The demarcation of the permissible from the impermissible is clear and strict. God intervenes only when his territory is affected and any problems are resolved through democratically determined procedures. Greek polytheism manages to include multiple reality, without setting aside contradictions or denying any part of the world.