The Greek civilization through the Ages

The study of Greek history is a profound exploration of the human experience, offering a rich and complex tapestry of events, individuals, and ideas that have left an indelible mark on the development of Western civilization. Rooted in a geographical crossroads of the ancient world, Greece’s historical timeline is a testament to the interplay of geography, politics, culture, and intellect. This exploration takes us on a chronological odyssey through the annals of time, as we trace the evolution of Greek society, politics, culture, and thought from its earliest known origins to its modern history manifestation.

The historical continuum of Greece reveals itself as an intricate interplay of continuity and change. Spanning millennia, it encompasses epochs of remarkable intellectual and artistic achievement, punctuated by periods of conflict, conquest, and transformation. Within this narrative, we encounter seminal figures whose ideas continue to resonate in contemporary discourse. Philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle have shaped the contours of ethical and political thought. Epic poets like Homer have crafted foundational myths that resonate with themes of heroism, fate, and the human condition. Architects and sculptors have left an indelible imprint on the world’s artistic heritage through structures like the Parthenon and sculptures like the Venus de Milo.

Moreover, Greece’s history is emblematic of the rise and fall of great empires and the enduring legacy of cultural exchange. It bears witness to the emergence of the world’s first known democracy in Athens and the profound influence of Greek political thought on subsequent systems of governance. It encompasses the conquests of Alexander the Great, which spread Hellenistic culture across vast territories, fostering the fusion of Eastern and Western traditions.

The Roman period of Greece, which began in 146 BC and lasted until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476, marked a significant chapter in the nation’s history. Greece, known as the “Hellenistic East,” was absorbed into the expanding Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire.

During this era, Greece experienced a complex blend of Roman rule and Hellenistic culture. The Romans respected Greek intellectual and cultural achievements, and many Greek cities retained their autonomy, with the local elite playing crucial roles in Roman administration.

The Byzantine Empire, rooted in Greek traditions, became a beacon of Eastern Christianity and a custodian of classical knowledge during the Dark Ages.

In more recent centuries, the struggle of Greece for independence from Ottoman rule ignited a fervor for national identity and self-determination. The Greek war of independence in the 19th century rekindled the spirit of democracy and led to the formation of the modern Greek state.

The chronicle of Greek history unfolds as a mosaic of cultural, political, and intellectual achievements and challenges. It is a testament to the enduring human quest for knowledge, identity, and self-determination. As we embark on this journey through the timeline of Greek history, we are drawn into a compelling narrative that transcends temporal boundaries, providing invaluable insights into the human condition, the evolution of societies, and the resilience of a culture that continues to captivate and inspire scholars and thinkers worldwide.

Paleolithic Period

Though there is very little information about the Paleolithic man of Greece, it is believed that there existed in Greece a type of human from that distant period who belonged to the nomadic or semi-nomadic category. However, we have abundant information about the Neolithic culture of Greece (end of the 7th millennium to mid 3rd millennium BC). In Crete, the presence of human life was identified as far back as the 6th millennium.

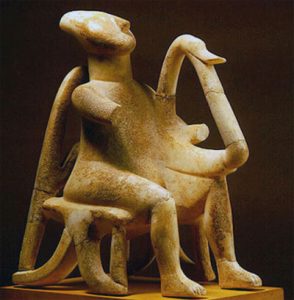

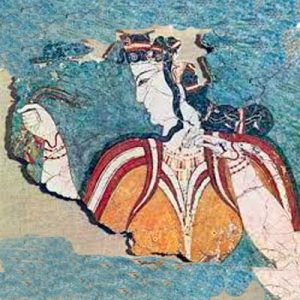

Neolithic settlements from the 4th millennium were discovered in Thessaly, Boeotia, Argolis, and other areas. Recent excavations have brought to light Neolithic remains even in Attica (Acropolis, Rafina, Cape Agios Kosmas). Houses from this period were built of stone and clay, and tools were made of stone, primarily obsidian from Milos. With the end of this period, the Bronze Age began, discoveries of which reveal the existence of life across nearly all of Greece, with the Cyclades islands as the cultural center.

The people who lived during these periods in the Greek territory are commonly named the Aegeans because they developed around the region of the Aegean Sea. They are also called the Pre-Greeks because they lived here before the arrival of the Greeks. Depending on where their culture developed, they were called Minoan or Cretan, Cycladic, Mycenaean, etc. The influx of Greek tribes into the region of Greece began in prehistoric times. The Ionians first arrived at the beginning of the 2nd millennium, followed by the Aeolians, Achaeans in the 14th and 13th centuries BC, and lastly, the Dorians in the 11th century. Historically, it was believed that the descent of the Greek tribes came from the North. However, recent research challenges this view, suggesting they came from the East and followed the maritime route between the Aegean islands.

The invasion of the Dorians severely disrupted the Greek territory. A pastoral people armed with iron weapons, the Dorians flooded Thessaly, Central Greece, Peloponnese, and from there headed to the Aegean islands and Crete. Only Attica, Arcadia, and for a while, Messinia, escaped the Dorian invasion. A faction of Dorians settled in Laconia, where, as Spartans, they played a significant role in Greek history. Research has not yet confirmed whether the collapse of the Minoan culture was due to the invasion of the Dorian tribes or coincided with a period of significant natural disasters (earthquakes) that weakened the Minoan kingdoms.

It’s a fact that the Dorians encountered little resistance in their expansion into areas where the Minoan culture had flourished. In the face of the Dorian onslaught, many were forced to migrate towards the Aegean islands and the coasts of Asia Minor. But Dorian settlers also followed this migratory trend. This represents the first Greek colonization, at the end of which the Greeks were divided into four tribes: the Achaeans, Dorians, Ionians, and Aeolians. The most important colonies from this period were Cyme, Smyrna, the Ionian Twelve Cities, the Dorian Hexapolis, among others.

Historical Times

Archaic Period (8th-6th century BC)

The most significant event of this period was the formation of the city-state in the Greek region, the abolition of monarchy, and later, the rise of tyranny. Over time, two cities emerged: the aristocratic Sparta, which after the Messenian Wars (734-724 BC and 645-628 BC) dominated the entire Peloponnese, and Athens, which shifted its focus to maritime trade after its transition from tyranny to democracy.

Second Greek Colonization (750-550 BC)

During this era, there was a strong migratory movement from mainland Greece and the Anatolian cities in all directions of the Mediterranean. Colonies were established on the coasts of the Hellespont and the Black Sea (Abydos, Lampsacus, Cyzicus, Sinope, Trapezus, Olbia, Istros, Odessus, Tanais, Phasis, etc.), at the mouths of the Nile (Naucratis), in Spain (Massalia, Mainake), in Corsica (Alalia), in southern Italy (Elea, Cumae, Rhegium, Gela, Acragas, Tarentum, etc.), in Sicily (Zancle, Naxos, Syracuse, etc.), in North Africa (Cyrene, Barca) and so on.

The main reasons for this massive movement were economic, such as the need for raw materials and foodstuffs, and the search for new trade routes, etc. Other reasons included overpopulation and political disturbances, which forced parts of the population to leave their metropolitan cities. The results of this colonization were brilliant: the colonists quickly developed economically, built beautiful cities, created new terms of social and political life, and developed a significant intellectual and artistic culture. The center of Greek culture then shifted to southern Italy and Sicily, which, due to the abundance of their colonies, were named “Magna Graecia”.

Persian Wars

Towards the end of the 6th century BC, the Persians subjugated the Greek colonies of Asia Minor and established tyrants in each one. Among these tyrants, Aristagoras of Miletus fell out of favor with the Persian king Darius and sought to revolt. He incited a rebellion in Miletus (499 BC) against the Persians and requested assistance from mainland Greece. Sparta refused, but Athens and Eretria sent ships and troops. With their help, the Greeks of Asia Minor managed to capture Sardis. However, the operation ultimately failed, and Darius, after once again subjugating the colonies and destroying Miletus (493 BC), turned against Athens and Eretria to avenge them for aiding the Ionians. The Persians’ first expedition to Greece took place in 492 BC under Darius’s son-in-law, Mardonius. However, his army faced major difficulties in Thrace, and his fleet, while passing the Athos peninsula, encountered a storm and lost 300 ships. Due to this setback, Mardonius was forced to return to Asia without achieving his goals.

Golden Age of Athens

In 478 B.C., the Delian League was established, in which member cities were nominally equal, but in reality increasingly came under the dominance of the Athenians. From 478-431 B.C., under the dynamic leadership of Aristides, Cimon, and especially Pericles (443-429), Athens experienced its “Golden Age”, becoming the foremost political and cultural center of ancient Greece and the strongest naval power. It also cemented the ancient democratic system by finalizing new institutions, namely the Boule (Council), the Ecclesia (Assembly) of the Demos, and the Heliaia (Court).

Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.)

The growing power and influence of Athens among the Greek world aroused the envy of Sparta, and it wasn’t long before the two superpowers of the time clashed. The ensuing war lasted 27 years and was the most devastating conflict in Greek history. The military campaigns of the Peloponnesian War are divided into three periods: the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), the Sicilian Expedition (415-413 B.C.), and the Decelean War (431-404 B.C.).

Archidamian War

In 431 B.C., the Spartans invaded Attica and ravaged the countryside. That winter, the Athenians buried their first war dead, and Pericles delivered his famous “Funeral Oration”, preserved by Thucydides in his history, which essentially praises Athenian democracy. In 429, Pericles died, and in 428, Lesbos rebelled against the Athenian alliance. After these setbacks, under the leadership of Cleon, the Athenians achieved a victory, capturing Pylos and Sphacteria. However, in 422, Cleon was killed at Amphipolis, fighting against the Spartan general Brasidas, and the following year (421) the “Peace of Nicias” was signed.

Sicilian Expedition

This proved to be Athens’ greatest failure. Alcibiades led them into it, believing that by conquering Sicily, Athens would gain an advantage over the Spartans, eventually forcing them to yield. However, the Syracusans defeated the Athenians; out of 40,000, only 7,000 survived. The victors enslaved the rest, with many working in the quarries.

Decelean War

In 431 B.C., the Spartans invaded Attica and fortified Decelea, cutting off Athens from the silver mines of Laurium and its allied cities. From this event, this war period took its name. The Athenians’ only significant victory during this period was the defeat of the Spartan fleet near the Arginusae islands (406 B.C.). Yet the victors were later sentenced to death because they failed to retrieve the dead from the sea. Lysander, who later assumed command of the Spartans, defeated the Athenians at the Battle of Aegospotami (405 B.C.), sailed to Piraeus, and blockaded Athens by sea. This was the last military action, as the Athenians were forced to surrender under humiliating terms.

The Hegemony of Sparta (404-371 BC).

After his victory over the Athenians, Lysander abolished all democracies and imposed oligarchic regimes in Greek cities. In Athens, he installed the “Thirty Tyrants” with Critias as their leader. However, the following year, Thrasybulus, with a small force of patriot exiles, overthrew the tyrannical regime of the Thirty and restored democracy to Athens.

The most significant event after the Peloponnesian War was Sparta’s conflict with the Persians. Here’s how the events unfolded: Cyrus, the satrap of Lydia, decided to dethrone his brother Artaxerxes and become the king of Persia himself. His army included 13,000 Greek mercenaries led by Clearchus. In the battle near Cunaxa, Cyrus was defeated and killed (401 BC).

The Greeks, after many adventures, managed to reach Trapezus (modern-day Trabzon) and from there crossed into Thrace. Xenophon describes this expedition and return (“The March of the Ten Thousand”) in his work “Anabasis.” However, Artaxerxes wanted to punish the Ionian Greeks who had supported Cyrus. The Ionians sought the help of the Spartans, who quickly responded and defeated the Persians. But the Persians didn’t give up; they financially strengthened many Greek cities and the Athenians and turned them against Sparta, initiating a new civil war, the Boeotian War.

Boeotian or Corinthian War (395-387 BC).

First, Thebes allied with the Persians, and later this alliance was joined by Athens, Corinth, and Argos. In 394 BC, they defeated the Spartans at the Battle of Haliartus, where Lysander, the mastermind behind Sparta’s tyranny, was killed. Sparta was then in grave danger and recalled Agesilaus from Asia, who, heeding the call of his homeland, abandoned his plan to overthrow the Persian throne. Fighting his way through Thrace and Macedonia, he reached Coronea where the allies awaited. The battle was challenging for the Spartans, but they ultimately won thanks to Agesilaus (394 BC). The victory at Coronea consolidated Sparta’s hegemony on land. Still, Conon, the admiral of the Athenian and allied fleet, maintained maritime dominance (393 BC). Later, with their envoy Antalcidas, Sparta concluded the “Peace of Antalcidas” (or the King’s Peace) with the Persians in 387 BC. According to this agreement, all Greek cities of Asia Minor, including Clazomenae and Cyprus, were to submit to the Persians. Only Imbros, Lemnos, and Skyros were allowed for the Athenians. All other Greek cities were to remain free.

The Theban Hegemony.

With the help of the Spartan general Phoebidas, the oligarchic Thebans Leontiades and Archias overthrew the democracy in their homeland in 382 BC. Under Spartan protection, they ruled tyrannically for three years. However, 400 democratic exiles returned to Thebes and, with the help of the Athenians, restored the democracy. Two great men then took over the governance of Thebes, Pelopidas and Epaminondas, who favored the establishment of the Second Athenian League (378 BC), as they pinned their hopes on it for the downfall of Sparta.

However, when their hopes were dashed and Athens allied with Sparta, the two co-generals continued the war against the Spartans on their own (371-362 BC). In 371 BC, they defeated the Spartans at Leuctra, and the following year, Epaminondas invaded the Peloponnese, liberated Messenia, and confined the Spartans to Laconia. Thus, the Thebans became the dominant power in Greece.

In 363 BC, Pelopidas was killed, fighting in Thessaly against the tyrant Alexander of Pherae, and the following year (362 BC), Epaminondas died in the Battle of Mantinea, fighting against the Spartans.

After the Battle of Mantinea, there was more turmoil in Greece than ever before. This war was certainly the final blow to Spartan hegemony, but it did not solidify Theban power. The following year, they agreed upon and signed a peace treaty, following the advice left by Epaminondas.

Hellenistic Times

Macedonian Hegemony

The civil wars drained the Greek city-states. The resurgence of Sparta and Thebes was temporary, and the Athenian regime began to irreparably deteriorate. At this point, a new power emerged on the scene – the centralized military state of Macedonia. Led by Philip II (359-336 BCE), son of Amyntas III, it was destined to overthrow the city-state regimes, despite their efforts to form larger political unions. In 357 BCE, Philip seized Amphipolis and, in 356 BCE, Potidaea and the gold mines of Thrace. He then suppressed the revolt of the Illyrians, Paeonians, and Thracians, securing his northern borders.

Therefore, when during the Second Sacred War (355-346 BCE) the Phocians invaded Thessaly, Philip accepted the Thessalians’ request for assistance, seeing it as an opportunity to intervene in the affairs of southern Greece. After driving out the invading Phocians, he simultaneously became the master of all Thessaly and appeared to the Greeks as the protector of the Delphi sanctuary. In 352 BCE, he campaigned in Thrace and reached the Propontis, and in 349 BCE he took Olynthus, despite the objections of the Athenian orator Demosthenes.

The indifference of the Athenians allowed him to dominate the entire Chalcidice. After this success, he concluded the Peace of Philocrates with the Athenians in 346 BCE and soon after took Phocis. In 344 BCE, the Thessalians elected him as their leader, and subsequently, Messenia, Megalopolis, Argos, Elis, Euboea, Epirus, and Thrace became his allies.

The Third Sacred War (339 BCE) provided Philip the opportunity to seize Amfissa and Elateia, revealing his intention for a definitive showdown with southern Greece. The battle took place in Chaeronea in 338 BCE, where he defeated the combined forces of the Athenians, Thebans, Phocians, Corinthians, and Achaeans. He then subjected all of Southern Greece and appointed oligarchic governments in the cities made up of “Philippizers”.

At the Corinthian congress he organized shortly after, he imposed a Panhellenic union, of which he appointed himself the leader. After this achievement, while organizing a campaign against the Persians, he was assassinated in the spring of 336 BCE.

Alexander the Great (336-323 BCE)

After Philip, his son Alexander succeeded him. In a pan-Hellenic congress convened in Corinth, Alexander was declared the autocrat’s general. Immediately afterward, he turned against the barbarians on the northern borders of his empire. At that time, it was rumored that Alexander had been killed in this campaign, leading to a revolt by the Thebans. In response, Alexander returned and destroyed Thebes in 335 BCE. This swift and brutal action terrorized other Greeks, who promptly submitted, allowing Alexander to focus on preparing for his campaign in Asia.

In 334 BCE, with 30,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry, Alexander crossed into Asia, leaving the governance of Greece to his general Antipater. His first victorious battle against the Persians occurred at the Granicus River (334 BCE). Subsequently, he conquered Phrygia, Lydia, Ephesus, Miletus, Halicarnassus, Caria, Lycia, Pamphylia, and advanced into Greater Phrygia. He took Kelainai without a battle and proceeded towards Gordium.

After famously cutting the “Gordian Knot,” he advanced into Paphlagonia and Cappadocia, crossed the River Halys, and subjugated the cities of Pontus. He then turned south, reaching Cilicia, capturing the “Cilician Gates,” and subjugating mountainous Lycaonia, Soloi, and the highlands of Cilicia, among other neighboring regions. In 333 BCE, he defeated the massive forces of Darius (400,000 infantry and 100,000 cavalry) at Issus, where Darius, with only 4,000 soldiers, crossed the Euphrates River to escape.

In a subsequent campaign, Alexander conquered Phoenicia, Palestine, Cyprus, and Egypt (332 BCE). The Egyptians received him with enthusiasm, and their priests deified him. Afterward, he visited the shrine of Ammon Zeus in the Libyan desert of Siwa, founded Alexandria, and spent five months in Egypt before returning to Tyre (331 BCE) to continue his campaign from there. The decisive victory over Darius was achieved at Gaugamela (331 BCE).

The vast army of Darius, consisting of 800,000 infantry, 200,000 cavalry, and 200 scythed chariots, disintegrated, and Darius himself fled from the battle, heading towards Ecbatana. Alexander then moved towards Babylon, captured it, and seized Darius’s treasures. He repeated this in Susa a month later. Subsequently, he captured the two sacred Persian cities, Pasargadae and Persepolis, where the palaces of the Persian dynasty were located. Meanwhile, Darius had been captured by the satrap Bessus. Alexander moved against Bessus, defeated him, but during Bessus’s escape, he killed Darius and declared himself king. Alexander pursued Bessus to Bactria, where he apprehended him and handed him over to the Persians, who crucified him.

In 327 BCE, after the conquest of the Persian Empire, Alexander embarked on an expedition to conquer India. He crossed the Indus River, defeated King Porus at the Hydaspes River, crossed the Plain of the Five Rivers, and reached the last, the Hyphasis, where his Macedonians refused to continue the campaign. Alexander was forced to retreat, returned to Persia, and settled in Susa. There, he focused on organizing his state and plans for the fusion and peaceful coexistence of the barbarian and Greek worlds into one nationality, through the transmission of Greek culture.

In 324 BCE, he campaigned against the mountain-dwelling Cissians, defeated them, and returned to Babylon, where he began preparing for a grand naval expedition. Suddenly, however, he fell seriously ill with a fever and, after 11 days, in June of 323 BCE, he passed away at the age of 33.

The Successors of Alexander the Great

Following the death of Alexander the Great, the dissolution of his vast empire was inevitable. The absence of a clear successor and the rivalries among his generals were the main causes of its fragmentation into small kingdoms. These conflicts persisted for over 20 years (323-301 BCE), during which Greece and Asia were often ravaged by wars.

Around 306 BCE, the most powerful of the satrap governors assumed the title of king. Antigonus, who held sway in Asia, set the precedent. This was followed by Ptolemy in Egypt, Lysimachus in Thrace, Seleucus in Babylon, and Cassander, the son of Antipater, in Greece. Nevertheless, wars continued among them until they all united against Antigonus, defeated him, and killed him at the Battle of Ipsus (301 BCE), subsequently dividing his territories. However, even those who remained came into conflict with each other. Finally, by 278 BCE, only three large and powerful states remained: Macedonia under the Antigonids, Asia under the Seleucids, and Egypt under the Ptolemies.

The kingdom of Macedonia, despite civil wars, anarchy, and the Galatian invasion (280 BCE), was founded by Antigonus Gonatas (278 BCE), who saved it and left it to his descendants. The Seleucid state was colossal, encompassing Asian territories up to the Bosporus, the Aegean Sea, and the Mediterranean. It also indirectly controlled Armenia, Cappadocia, Pontus, Paphlagonia, Bithynia, and Pergamon, all of which had their own rulers but fell under the influence of Hellenism and worked to spread Greek culture. Rhodes thrived as an independent commercial and naval power, while Delos, with the help of Macedonian kings, became a center for the trade of grain and slaves. Its prosperity continued into the Roman era until its destruction during the Mithridatic Wars in 88 BCE.

Among the Hellenistic-era kings, two stood out: Demetrius Poliorcetes, who, in addition to other war machines, invented and employed the famous “helepolis” in sieges—a nine-story tower that was moved on four strong wheels, measuring 45 cubits on each side and 90 cubits in height, requiring 200 men to operate.

The other notable figure was King Pyrrhus of Epirus, who attempted to achieve in the West what Alexander had in the East. He accepted the Tarantine proposal and went to Italy as their ally against the Romans. Pyrrhus defeated the Romans at Heraclea (280 BCE) and Asculum (279 BCE) but was defeated at Beneventum (275 BCE) and forced to return to Epirus empty-handed. In 274 BCE, he subjugated Macedonia and then turned his attention to the Peloponnese, where he met an accidental death in Argos.

Aetolian and Achaean League

The remaining cities in mainland Greece retained their autonomy but had been exhausted by civil wars and revolutions. Only the Aetolians and the Achaeans showed some vitality and sought to achieve unity among the Greeks. Thus, the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues emerged.

According to the organization of the Aetolian League, every year at the “Panaitolion” conference in Thermos, representatives from various cities convened to make decisions regarding war or peace. Apart from this common assembly, there was another council known as the “Apokletoi,” representing the nobles of the country. The supreme ruler, the strategos, was chosen from among them, and his election was ratified by the assembly. The second-ranking official of the League was the hipparch, and the third was the public secretary. In the mid-3rd century BCE, the Aetolian League welcomed Kephalonia, Elis, Messenia, some Arcadian cities, the Locrians, the Phocians, the Boeotians, and some Thessalian cities into its alliance.

The Achaeans, in 281 BCE, formed their League with ten cities whose representatives gathered in Aegium to make decisions regarding war, peace, and alliances. The executive authority was held by two strategoi and one secretary. Later, the second strategos was called the hipparch. In addition to the strategoi, there was a council of ten men known as “demiourgoi,” representing the ten allied cities.

In 250 BCE, Sikyon was incorporated into the Achaean League by Sikyonian Aratus, who became the driving force behind the League and fought against tyrannical regimes and Macedonian rule. For thirty years (245-213 BCE), every other year, a strategos was elected. Aratus added Argos, Corinth, Megara, and others to the League and almost united the entire Peloponnese. He was succeeded by Philopoemen of Megalopolis (253-189 BCE), who even forced Sparta to join the League. He was called “the last of the Greeks” from ancient times because with his death, the last effort to preserve Greece’s freedom came to an end. Roman propaganda, with the collaboration of Callikrates, ultimately dissolved the League

Greece under the Roman Rule

The Roman threat to Greece emerged in 229 BCE when the Romans established themselves on the shores of Illyria. At that time, the Greeks were divided and plagued by civil wars, such as the conflict between the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues, known as the Social War (227-217 BCE).

This situation favored the Romans in their conquests. They defeated King Philip V of Macedon at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 200 BCE, near Pharsalus, and forced him to withdraw from all his possessions in Asia Minor, Thrace, Southern Greece, and the Aegean Islands.

In 190 BCE, near Magnesia, they defeated Antiochus III and compelled him to cede all his European possessions and Asia Minor to them, thus dissolving the Seleucid Empire. In 168 BCE, at the Battle of Pydna, they defeated Perseus and subjugated all of Macedonia.

Finally, in 146 BCE, the Roman general Mummius captured Corinth, looted and destroyed the city, and slaughtered or enslaved its inhabitants. This violent campaign led Rome to subdue all of Greece. The Greeks lost their political independence. Despite their suffering, Hellenism triumphed over its conqueror in a short period, influencing the creation of Roman culture.

The words of the Roman poet Horace are worth mentioning: “Although Greece was captured, she conquered her savage conqueror and brought the Arts to rustic Latium.”

The Romans not only did not obliterate Greek civilization but, on the contrary, respected it, honored it, and cultivated it in their homeland. They studied everything that was Greek, including language, literature, philosophy, law, and rhetoric. Even the emergence of Christianity solidified Hellenism in both the East and the West, as the language in which the sacred texts were written and the new religion was taught was Greek.

Thus, from the vast Roman Empire, which extended from the Atlantic Ocean to the Euphrates River and from the English Channel and the North Sea to the cataracts of the Nile and the great desert of North Africa, arose the Greco-Christian Byzantine Empire.

Byzantine Times (330-1453 CE)

The founder of the Byzantine Empire, the Eastern Roman state, is considered to be Constantine the Great (306-387 CE), the son of Emperor Constantius. He was declared a god by the Roman Senate, known as great in history, and recognized as a saint and apostle by the Christian Church.

However, the full Hellenization of the Eastern Roman state occurred later, after the final dissolution of the Roman Empire following the death of Theodosius I in 395 CE. At that time, Theodosius’s two sons, Honorius and Arcadius, became emperors in the West and East respectively.

The Western Roman state followed its independent course and soon disintegrated under the pressure of various barbarian tribes such as the Scythians and Goths who flooded Europe in the following centuries. In contrast, the Eastern part gave rise to the Byzantine Empire.

The Hellenization of the Eastern Roman state ushered in a new period in Greek history, lasting over a thousand years. It experienced a particularly great flourishing during the reigns of emperors like Justinian, Heraclius, and the Macedonian Dynasty, the Comneni, and the Palaiologoi, before coming to an end with the emergence of the Seljuk Turks.

These new conquerors, after establishing dominance over the Arab state of Baghdad, Persia, Armenia, Cappadocia, and capturing Iconium (Konya) and Nicaea, arrived at the gates of Constantinople in 1079. After nearly three centuries of struggle, they eventually subjugated the entire Byzantine Empire in 1453.

Turkish rule 1453 – 1827

After the fall of Constantinople, the conquest of the remaining Greek territories continued and was completed. In 1456, the Duchy of Athens was dissolved, in 1460, the Despotate of Mistra, and in 1461, the Empire of Trebizond. In place of a people with great cultural strength, another people, barbaric and uncivilized, who were unable to assimilate and continue the civilization they found, emerged. Thus, the entire region of the Eastern Mediterranean, including Greece, plunged into medieval barbarism. The blow was heavy, but Hellenism did not fade away. It continued to exist under the strong influence of Byzantium, hoping for a revival and rebirth of the nation.

The Sultan recognized the Greek Orthodox Church as an official institution within his state and granted certain privileges to the Ecumenical Patriarch, making him the ethnarcho, meaning the religious and political leader of the enslaved Greeks. The first Patriarch after the Fall was the scholar Gennadius Scholarius. The Sultan even granted some privileges of communal self-government to allow the Turks to focus on warfare and easily collect taxes. However, these religious and communal privileges were rudimentary and insufficient to balance the suffering of the enslaved Greeks. Depositions, imprisonments, or killings of clergy were frequent occurrences. Education was neglected, and the lives, honor, and property of the rayahs (slaves) were at the mercy of the Turks. Through the head tax (haratsi) and various other taxes, the Turkish rulers became wealthy, while the Greeks suffered economic hardship.

However, the most terrible tax was the ‘blood tax,’ the infamous devshirme. During the first two centuries of enslavement, the Turks abducted a million Greek boys to populate the Janissary corps. Violent conversions to Islam were also common. Nevertheless, nothing could shake the national spirit of the Greeks and diminish their awareness of their ethnic identity. They were aided in this by insurmountable differences between themselves and their Asian conquerors, such as religious fanaticism, customs and traditions, lifestyles, and general mentality. Greek spirit found numerous ways to manifest itself and achieve remarkable results, as seen in the exceptional progress of communities like Chios, Rhodes, Tinos, Naxos, Hydra, Spetses, Psara, and especially the 24 villages of Pelion, Ampelakia, and Mademochoria. Additionally, a dynamic group of Greeks, the Phanariotes, taking advantage of the Turks’ incompetence, managed to rise to high-ranking positions within the state apparatus.

They became interpreters, administrators of foreign policy, leaders of the Danubian principalities (Mavrokordatos, Ypsilantis, Karatzas, Soutsos, etc.), and in various ways, they benefited the enslaved nation. Over time, the enslaved nation gained its military power, the klephts (brigands) and armatoloi (militia). Many Greeks took to the mountains and fought against the Turks, who scornfully called them ‘klephts.’ However, the klephts represented for Hellenism the resistance force of the nation and embodied the highest notion of Greek courage. To counter the klephts, the Turks adopted the institution of armatoloi, a revival of the Byzantine ‘akrites.’ They divided the country into ‘armatoliks,’ each led by a ‘captain.’

At the beginning of the 19th century, there were 3 armatoliks in Macedonia, 10 in Thessaly and Eastern Central Greece, and 4 in Epirus, Acarnania, and Aetolia. In the Peloponnese, klepht-armatolism did not thrive. Between the klephts and armatoloi, there was no hostility. This is evident from the fact that they easily switched sides, and over time, the two concepts became indistinguishable. Klephts and armatoloi led in all the nation’s uprisings and were the principal force during the outbreak and conduct of the Revolution of 1821.

Modern times

The modern period of Greece refers to the time after Greece gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1821 following the Greek War of Independence. This historical period saw the creation and development of the modern Greek state, as well as significant political, economic, social, and cultural changes.

In the early years of independence, Greece faced many challenges such as securing its borders, forming a government, and building a national identity. The first king of Greece, Otto, was imported from Bavaria to help establish the new state and modernize the country. Under King Otto’s reign, new institutions were created, including the Greek army and navy, and the country’s infrastructure was improved with the construction of roads, railways, and public buildings.

During the 20th century, Greece experienced periods of political instability and economic hardship, including two world wars, a civil war, and periods of military dictatorship. However, the country also underwent significant social and cultural changes during this time. In the post-war period, Greece experienced an economic boom, known as the Greek Economic Miracle, and the country’s culture and arts flourished, with the development of new literary movements, music, and cinem