Modern Greek History : From Independence to Present

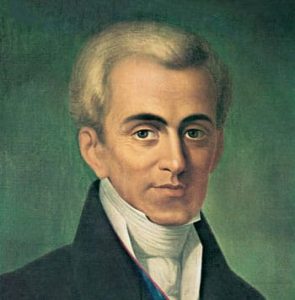

After the Greek revolution of 1821 and finally the establishment of the Modern independent Greek state in 1830 with the Treaty of London, Its territorial area included parts of Sterea Ellas, the islands of Evia, Sporades, Cyclades and the Peloponnese, unrest prevailed in the country. Kapodistrias the first Governor of Greece, ruled in a dictatorial way until he was assassinated in 1831, which was followed by civil war.

The year after the 17 year old Bavarian prince Otto was declared king of Greece. He was not popular for many reasons: he was not Greek, delayed a constitution to be made, and he taxed the people heavily.

He was forced to make a constitution after a rebellion in September 3 of 1843. Otto became even less popular when he helped the French and English during their embargo of Piraeus to prevent an alliance between Greece and Russia during the Crimean War (1854-1856).

Otto was deposed in 1862 and the Danish prince George was crowned king of Greece after the British had suggested him. Because the Greeks accepted him, the British gave the Ionian islands back to Greece.

War against Turkey started again in 1878 after Greece had decided to win back some of its old territory. After years of embargoes, negotiations and revolts, Turkey gave back Thessaly and Arta to Greece.

The economical growth of Greece begun in the 19th century. Roads and railroads were built, the Corinth channel was finished and Piraeus became an important commercial harbour. Battles with Turkey continued though, and Crete was put under international rule. The island finally unified with the rest of Greece when the Cretan premier minister Eleftherios Venizelos ruled 1910-1935. Macedonia was still occupied by the Ottoman Empire.

Ioannis Kapodistrias.

In September, the French general Maison cleared the Peloponnese, forcing Ibrahim to leave with his Turkish-Egyptian troops. In June-August 1829 the Fourth National Assembly was convened in Argos and on September 12 Ypsilantis gave the last victory.

On January 22, 1830, the London Protocol was signed, which recognized the full independence of Greece and defined its borders with the Ottoman Empire (the Acheloos-Sperchios line,or Aspropotamos-Spercheios line) with the islands Evia, the Sporades and the Cyclades becoming part of Greece. On September 9, Kapodistrias was assassinated in Nafplio and in this violent way the first period of life of the free state is interrupted.

The Reign Of king Otto of Bayern

After the assassination of Kapodistrias, an administrative committee was formed, chaired by Ioannis Kapodistrias’ younger brother, Augustinos Kapodistrias. The following year the Ninth National Assembly met in the Welfare of Nafplio and elected the Bavarian prince Otto, who landed in Nafplio on January 25, 1833, as king. On September 18, 1834, Athens was declared the capital and the transfer of this from Nafplio took place on December 1. On November 10, 1836, Otto married Duchess Amalia of Oldenberg. On May 3, 1837, the University of Athens was founded. In 1838 the day of the Annunciation was celebrated for the first time as the anniversary of the National Rebirth.

On May 30, 1841, the National Bank of Greece was established and in 1842, the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens was constructed.. On September 3, 1843 a revolution broke out and Otto was forced to grant a Constitution.

Throughout his reign Otto was unable to resolve Greece’s poverty and prevent economic meddling from outside. Greek politics in this era were based on affiliations with the three Great Powers that had guaranteed Greece’s independence, Britain, France and Russia, and Otto’s ability to maintain the support of the powers was key to his remaining in power. To remain strong, Otto had to play the interests of each of the Great Powers’ Greek adherents against the others, while not irritating the Great Powers. When Greece was blockaded by the British Royal Navy in 1850 and again in 1854, to stop Greece from attacking the Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War, Otto’s standing amongst Greeks suffered. As a result, there was an assassination attempt on Queen Amalia, and finally in 1862 Otto was deposed while in the countryside. He died in exile in Bavaria in 1867 .

Greek Constitution of 1844

The Greek Constitution of 1844 holds a significant place in the history of Greece, marking the country’s first step towards a constitutional monarchy after a period of absolute monarchy under King Otto of Bavaria, who had been placed on the Greek throne by the Great Powers (Britain, France, and Russia) following Greece’s War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire.

The arrival of King Otto in 1832 marked the beginning of a new era for Greece, which was emerging from the ruins of a long and devastating war of independence. Initially, King Otto ruled as an absolute monarch, without a constitution, relying on Bavarian regents and advisors to govern. This situation led to growing discontent among the Greek population, which yearned for a more democratic form of governance and greater participation in the affairs of state.

The demand for a constitution and representative governance grew louder throughout the 1830s and early 1840s, culminating in a military uprising in 1843. The uprising, led by military officers and supported by a wide cross-section of Greek society, forced King Otto to concede to the demand for a constitutional government.

The Constitution of 1844, promulgated on March 18, 1844, established Greece as a constitutional monarchy, significantly limiting the powers of the monarch and laying the foundation for parliamentary democracy. The constitution introduced several key principles and institutions that shaped the future of Greek governance.

The Reign Of George the First

The Ottoman Turks however strongly objected to this and the Prime Minister Trikoupis threatened war with Turkey. This was finally settled with the Treaty of Berlin,with the Turks concedingThessaly and a small part of Epirus in 1881. In 1885 the Bulgarians occupied eastern Romulia in a coup, uniting the province with Bulgaria. The Greek government’s main opposition, the Nationalist Party led by Theodoros Deligiannis won a victory in the Greek elections of that year by arguing that if the Bulgarians could defy the Treaty of Berlin then so can the Greeks.

Between 1882 and 1897 Trikoupis and Deligiannis alternated as Prime Minister as the country’s fortunes rose and fell. In 1893 Trikoupis was forced to declare the country bankrupt. In 1896 new revolutionary movements took place in Crete and Greece decided to help the revolutionaries, eventually leading to the declaration of the unfortunate war of 1897. But the following year Crete was declared autonomous; in 1905 the revolution of Therissos broke out, led by El. Venizelos, and in 1908 the union of Megalonisos with Greece was proclaimed (but it took place in 1912 and was internationally recognized in 1913). The Macedonian Struggle (1902-8) was held at the same time. Meanwhile, Bulgaria began voicing its claims to Macedonia.

Under the pretext of the liberation struggle against Turkey, the Bulgarians cultivated the autonomy of Macedonia, established schools and appeared as protectors of the Christians in the Ottoman Empire regardless of their nationality, while over time armed Bulgarian guerrilla forces, the Komitas, and the Bulgarian Macedonia in the schismatic Bulgarian Exarchate(the Bulgarian Orthodox Church) from 1870, without hesitation proceeded with persecution and terrorism against the Orthodox population, while the weak Turkish government was unable to take action against them.

From 1900, the organization of the Greeks of Macedonia began to strengthen the Greek efforts to win control of Macedonia. The Hellenic Macedonian Committee was formed in 1903 with the leadership of Dimitros Kalapothakis and its members included Ion Dragoumis, Germanos Karavangelis and Pavlos Melas. Dragoumis was made deputy consul in the Greek consulate a Monastir ,Germanos Karavangelis, was the Metropolitan Bishop of Kastoria, and Pavlos Melas , an officer of the Hellenic Army. All three were instrumental in the Greek struggle for Macedonia. Greece helped the Macedonians to resist both Ottoman and Bulgarian forces by sending military officers who formed bands made up of Maceddonians and other Greek volunteers. This became known as the Macedonian Struggle from 1904 to 1908 which ended with the Young Turk Revolution.

In 1909, the Military Association, led by N. Zorbas, attempted a coup d’etat which began at the barracks in Goudi, a neighbourhood on the eastern outskirts of Athens. This coup was an important event in Greek modern history as it brought to the political scene of Greece Elefherios Venizelos, who went on to become Prime Minister. The coup came about due to simmering tensions that existed as a result of the effects of the disastrous Greek-Turkish War of 1897. Influenced by the Young Turks, some junior army officers founded a secret society named the Military League, headed by Colonel Nikolaos Zorbas. The coup involved demanding an immediate change in the running of the country and its armed forces.

King George gave in and replaced Prime Minister Dimitrios Rallis with Kyriakoulis Mavromichalis. However, this did not satisfy the rebels and eventually the Cretan Venizelos, who, as a strong democrat, proceeded with reforms.

Greece in the Balkan Wars (1912-13)

The decline of the Ottoman Empire’s control over the Balkans had been evident for some time, creating a power vacuum that the Balkan states aimed to fill. Nationalistic fervor, coupled with the desire for expansion and the rectification of historical grievances, led to the formation of the Balkan League. Greece, under Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, joined this alliance, seeing an opportunity to liberate and annex Crete, Epirus, Macedonia, and the Aegean islands, regions with significant Greek populations.

The First Balkan War erupted in October 1912 when the Balkan League launched coordinated attacks against the Ottoman Empire. Greece’s strategic objectives were focused on Macedonia and Epirus, and to a lesser extent on the islands of the North Aegean. The Greek Army, under King Constantine I, achieved significant victories on the mainland, notably capturing the city of Thessaloniki just a day before the arrival of Bulgarian forces who also aimed to claim the city. This early capture of Thessaloniki was a strategic triumph for Greece and solidified its claim to the region.

Simultaneously, the Greek Navy played a crucial role in securing the Aegean Sea, effectively isolating the Ottoman forces in Europe from reinforcements from Asia Minor. The naval blockade and subsequent naval victories ensured Greek dominance in the Aegean and facilitated the liberation of several islands.

The First Balkan War concluded with the Treaty of London in May 1913, which significantly reduced Ottoman territories in the Balkans, leaving them with only a small foothold in Europe. Greece, along with its allies, gained substantial territories. However, the distribution of these lands, particularly Macedonia, soon became a point of contention among the victorious allies, laying the groundwork for the Second Balkan War.

Second Balkan War (1913)

Dissatisfied with the territorial divisions after the First Balkan War, Bulgaria launched surprise attacks against its former allies, Serbia and Greece, in June 1913. This conflict, known as the Second Balkan War, was marked by a swift response from Greece and Serbia, who were soon joined by Romania and the Ottoman Empire, both seeking to capitalize on Bulgaria’s isolation.

The Greek army, already mobilized and battle-hardened from the previous conflict, made significant gains in Macedonia, while the navy secured control of the Aegean Sea from any Bulgarian threat. The war ended with the Treaty of Bucharest in August 1913, which ratified the territorial gains made by Greece in the First Balkan War and allowed further expansions, particularly in Epirus and Crete, effectively doubling the country’s territory and giving it access to new populations and resources.

Impact and Legacy

The Balkan Wars were transformative for Greece, marking the beginning of a new era in Greek history. The wars facilitated the incorporation of territories with large Greek populations, fulfilling the national aspiration of uniting the Greek people within a single state. However, the new borders also sowed the seeds for future conflicts in the region, particularly with Bulgaria and Turkey, and within the newly acquired territories, where significant Muslim and Bulgarian populations were now part of Greece.

Moreover, the Balkan Wars boosted Greek national confidence and military prestige, setting the stage for Greece’s involvement in World War I and the subsequent Asia Minor Campaign.

Greece in the First World War (1914-1918)

When World War I was declared, there was a serious disagreement between Eleftherios Venizelos, who supported the participation of Greece in and the Germanophile King Constantine, who had the opposite opinion, favouring neutrality. This disagreement led to an ethnic division, which culminated in the division of the country into two territories. Athens and Constantine remained neutral, while the revolutionary National Defence government led by the triad of E. Venizelos, P. Daglis and P. Kountouriotis in Thessaloniki declared war (1916) against the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Turkey, Turkey). .

In 1917 Constantine was forced to abdicate and his son Alexander ascended the throne. Thus the state unity was restored and Venizelos returned from Crete back to Athens. During this war the Greek army crushed the Bulgarians in Skra and forced them to sign a truce (1918). In September of the same year, the Battle of Veternick-Golo Bilo and the Battle of Doirani took place.

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 (The Asia Minor Campaign – 1919-1922).

This war was fought between Greece and the Turkish National Movement during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War 1. It started primarily because the western Allies, in particular Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister of the time, had promised that Greece would gain territories from the defeated Ottoman Empire. In particular, the areas that had been part of Ancient Greece and the Byzantine Empire, such as Anatolia, would revert back to Greece.

Based on the treaties of Neigi (November 27, 1919) and Sevres (August 10, 1920), Eastern Thrace and the islands of Imbros and Tenedos and the region of Izmir were annexed to Greece, while the Paris Embassy Conference (November 1921) granted the North Continent. The Greek army occupied Thrace and lands in Smyrna, where it was accepted as a liberator.

In October 1920, however, King Alexander died, Venizelos was defeated in the elections and in November, after a referendum, Constantine returned to Greece. A new national division ensued. At the same time, the allies left Greece in an operation that exceeded its forces. Thus, after the advance of the Greek army to the Sangarios River, the country was led to the overwhelming defeat of 1922 and its military forces were forced to leave the territory of Asia Minor. The Asia Minor catastrophe resulted in the military coup of N. Plastiras and St. Gonata (September 1922), which forced Constantine to abdicate.

George II ascended the throne, while most members of the government of D. Gounaris, who was considered responsible for the disaster, were sentenced to death and executed (Trial of the Six). The final settlement of the borders was done with the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), by which the Greek-Turkish border is defined on the river Evros, the islands of Imbros and Tenedos were assigned to Turkey and the exchange of the Christian populations of Turkey and the Muslims of Greece was decided.

The Interwar Period (1922-1940).

In March 1924 the monarchy was declared deposed and replaced by a democracy, with Alexandros Zaimis. However, the political situation was very unstable resulting in General Pangalos declaring a dictatorship in 1925, but this was overthrown the following year. In 1928 the elections gave the majority to Venizelos and after four years to The People’s Party. A new period of instability followed, culminating in the return of George II (1935) and the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas (1936).

During this time Italy ruled the Ionian islands (1912-1947) and eastern Thrace was given to Turkey, along with a few islands. Constantine was king again after Alexander had died of a monkey-bite, but he abdicated after the catastrophe in Asia Minor. He was succeeded by his other son George II. His rule was short, though, since a group of officers seized power and proclaimed Greece a republic.

Years of constant coup d’etate followed, and Venizelos seized power in 1928. His party sat in the government until it lost the elections of 1933 against the monarchist party. The new party was about to reinforce the king when Venizelos and his followers tried to overthrow the new government, but failed and was exiled to Paris where he died a year later. King George II was back on the throne, and he named the general Ioannis Metaxas prime minister. The latter came to be a dictator with the kings blessings when they feared the communist party might try to take over.

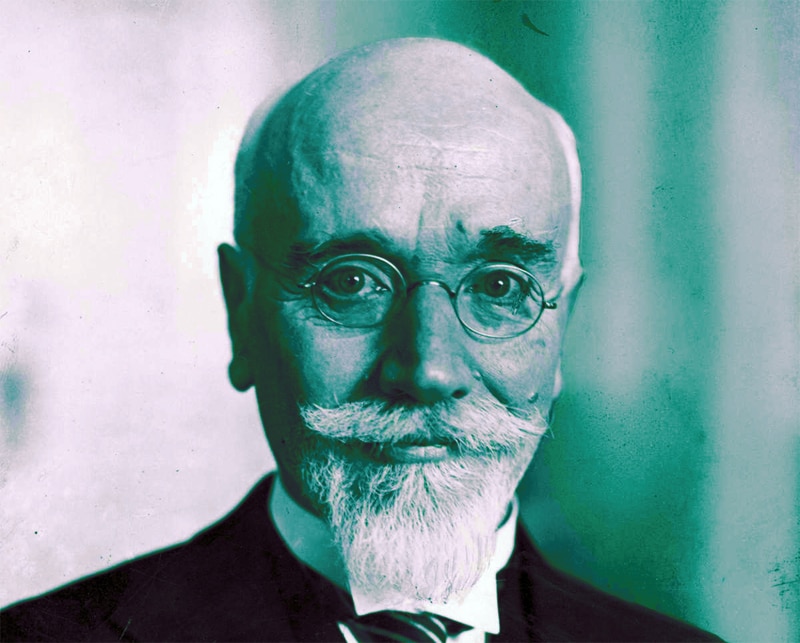

ELEFTHERIOS VENIZELOS

The Dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas

The dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas, often referred to as the 4th of August Regime, was a pivotal period in modern Greek history, lasting from 1936 until Metaxas’s death in January 1941. This era was marked by the establishment of an authoritarian regime that sought to suppress political dissent, modernize the Greek state, and foster a strong sense of national unity, all under the guise of protecting the nation from the twin threats of communism and fascism, which were tearing apart Europe at the time.

Ioannis Metaxas, a monarchist and former military officer, came to power in April 1936, appointed by King George II to head a government of national unity amid a period of political instability and social unrest in Greece. The pretext for the establishment of his regime was a strike on the Athens-Piraeus electric railway in July 1936, which Metaxas used to persuade the king to declare a state of emergency, suspend parliamentary rule, and impose martial law, citing the need to protect the nation from a communist revolution.

Once in power, Metaxas dissolved parliament, banned political parties, including the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), and established a security police to enforce the regime’s policies, leading to the arrest, exile, and torture of political opponents. The regime heavily censored the press, controlled the dissemination of information, and implemented a broad surveillance system to monitor and suppress any form of dissent.

Despite its authoritarian nature, the Metaxas regime sought to implement a number of reforms aimed at modernizing the Greek state and economy. These included efforts to industrialize the country, improve infrastructure, and create social welfare programs. Metaxas envisioned Greece as a “Third Hellenic Civilization,” drawing inspiration from the glory of Ancient Greece and the Byzantine Empire, and aimed to foster a strong national identity through education and youth organizations, such as the EON (National Youth Organization), which promoted physical fitness, patriotism, and loyalty to the state.

Culturally, the Metaxas regime promoted traditional Greek values, the Greek Orthodox faith, and the monarchy, attempting to unite the nation under a common identity. This cultural policy was part of a broader effort to counteract the influence of foreign ideologies, particularly communism and liberal democracy, which Metaxas believed were threats to the national fabric of Greece.

The foreign policy of the Metaxas regime was characterized by a delicate balancing act between the Axis powers and the Allies. Metaxas sought to maintain Greece’s neutrality in the face of growing international tensions leading up to World War II. However, this neutrality was shattered in October 1940 when Italy, under Mussolini, invaded Greece, leading to Greece’s entry into World War II on the side of the Allies. Metaxas’s leadership during the initial stages of the conflict, including his famous “Oxi” (No) response to the Italian ultimatum demanding free passage to occupy strategic sites within Greek territory, rallied the Greek population and led to significant Greek successes against the Italian forces

Greece in WW2

Despite the government’s efforts to stay out of the war, a series of Italian provocations, most notably the explosion of the frigate “Elli” in the port of Tinos (August 15, 1940), exacerbated the situation causing Greece to enter into the conflict.. In the early hours of October 28th, the Italian government, which had already occupied Albania and was seeking sovereignty over the entire Eastern Mediterranean, declared war on Greece, but the Greek army not only successfully repulsed the Italian attack, but within a few months and despite the heavy winter, it advanced on the Albanian Front and liberated the Northern Epirus. Only after the German attack (1941) did the Greek troops bow down and Greece was enslaved.

Metaxas died in January 1941 and the Prime Minister, Alexandros Koryzis died in April of that year. King George II sought for his successor eventually choosing Emmanouil Tsouderos to lead the new government. By early June 1941the country was under the occupation of the German, Italian and Bulgarian tripartite but before this occurred King George II and his government fled to Crete and after its occupation to the Middle East and Egypt to continue the fight against the Axis on the side of the allies. This was followed by a four-year occupation by Bulgarians in Thrace and German-Italians in the rest of Greece. The Greek government in Egypt, where with the participation of many Greeks who were secretly fleeing Greece, began developing Greek military corps (first, second and third Greek brigade, Holy Corps), which took part in war on the side of the Allies (El-Alamein, Rimini, North Africa). At the same time in Greece, the resistance action was organized with the most important organizations, E.AM.-E.L.AS and E.D.E.S.

The Greek army, although outmanned and outgunned, mounted a fierce resistance against the invading Italian forces. Pushing back the Italians, they managed to advance deep into Albanian territory, where the front lines stabilized for several months. This unexpected success of the Greek forces not only boosted Allied morale during a dark time in the war but also forced Nazi Germany to reassess its strategic plans in the Balkans.

Germany’s involvement came in the spring of 1941, as Hitler could not afford the weakness the Italian failure exposed, nor could he allow the British to establish a foothold in Greece that threatened his southern flank. In April 1941, German forces invaded Greece through Bulgaria, quickly breaking through the Metaxas Line, a series of fortifications along the Greek-Bulgarian border. Despite valiant efforts by Greek and British Commonwealth troops, the Germans swiftly overran the country. By the end of April, Athens had fallen, and the entirety of mainland Greece was under Axis occupation.

The occupation of Greece was characterized by harsh brutality, economic exploitation, and a devastating famine in the winter of 1941-1942 that led to tens of thousands of deaths. The country was divided into zones controlled by Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria, each enforcing repressive measures against the Greek population. The Greek people, however, did not submit quietly to Axis rule. A vigorous resistance movement emerged, comprising various groups with differing political affiliations, from royalists to communists. These groups waged a guerrilla war against the occupiers, significantly disrupting Axis operations and contributing to the Allied effort in the region.

One of the most notable episodes of resistance came in May 1941, when Greek forces on the island of Crete fiercely opposed the German airborne invasion. The Battle of Crete, although ultimately a German victory, inflicted heavy losses on elite German paratroopers and delayed further Axis operations in the Mediterranean. The courage displayed by the Cretans and the British Commonwealth forces during the battle remains a source of pride for Greece and is commemorated annually.

The liberation of Greece began in October 1944, as German forces withdrew from the mainland, allowing the Greek government-in-exile to return. However, the country’s liberation did not bring immediate peace. The political and social rifts that had widened during the occupation soon erupted into a civil war, which would last until 1949 and leave Greece profoundly scarred.

Greece’s participation in World War II is a testament to the resilience and courage of its people. The Greek resistance altered the course of the war in the Eastern Mediterranean, delaying Axis plans and providing a symbol of defiance against the Axis powers. The legacy of this period is complex, marked by heroism, tragedy, and the indomitable spirit of a nation fighting for its freedom.

The Greek resistance during WW2

The occupation of Greece was divided among Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria, each controlling different parts of the country and imposing brutal regimes. The economic exploitation, repressive policies, and the resulting famine in the winter of 1941-1942, which led to tens of thousands of deaths, fueled widespread anger and resistance among the Greek population.

The resistance in Greece was characterized by its diversity, with various groups emerging across the political spectrum, from royalists and republicans to communists and socialists. Despite their ideological differences, these groups were united in their opposition to the Axis occupiers. The two largest and most influential resistance organizations were the National Liberation Front (EAM) and its military wing, the Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS), both of which were aligned with the Communist Party of Greece, and the National Republican Greek League (EDES), which was more aligned with the British and the Greek government-in-exile.

The activities of the resistance ranged from sabotage and espionage to guerrilla warfare and the establishment of liberated zones in the mountains of Greece. These areas operated under their own administrative and military control, effectively creating a state within a state. The resistance was responsible for significant acts of sabotage, including the destruction of the Gorgopotamos viaduct in 1942, which was a major operation carried out jointly by EAM-ELAS and EDES forces, aided by British Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents. This operation significantly disrupted the Axis supply lines in the Balkans.

The resistance also played a vital role in saving thousands of Jews from the Holocaust, providing them with shelter and helping them escape from the occupied territories. The Greek Resistance’s efforts were not limited to military activities; they also included the creation of schools, hospitals, and other social services within the liberated zones, maintaining a semblance of normal life under extraordinary circumstances.

However, the Greek Resistance was not without its internal conflicts. Rivalries and ideological differences, particularly between EAM-ELAS and EDES, led to instances of civil conflict even before the liberation of Greece. These internal divisions would later escalate into a full-blown civil war after the end of the German occupation.

The liberation of Athens in October 1944 marked the end of the Axis occupation of Greece, but the legacy of the resistance movement would continue to influence Greek society and politics for decades to come. The resistance against the Axis occupiers showcased the determination of the Greek people to fight for their freedom and sovereignty, despite overwhelming odds. It also set the stage for the subsequent civil conflict that would emerge in the power vacuum left by the retreating Axis forces, shaping the political landscape of post-war Greece.

Greece after the WW2

In 1946 George II was back on the throne, and the monarchist party ruled the country. A new left-winged movement begun controlling large areas near Albania. USA had started watching Greece now instead of the UK, and because they feared the communist spread during the Cold War, they literally pumped the right wing party with money and weapons. The communist party was forbidden, and you had to carry with you a certain document the infamous “Harti Koinonikon Fronimaton” (paper of social believes) where it said you were not a follower of the left if you wanted to work and vote until 1962. This infamous paper though continued to hound many Greeks in matters of work as civil servants, passports, visas, army until the end of the Greek Military dictatorship in 1974.

The communists managed to conquer large areas of the Peloponnesus, but they were soon driven out by the government. In 1949 the right won the civil war after the Greek Communist Party was not anymore supported by Yugoslavia. This ended the civil war, but Greece was in extremely poor condition, and almost a million Greeks emigrated to countries like the USA, Australia, Germany and Sweden.

General Papagos became the new prime minister and when he died in 1955 he was succeeded by Konstantinos Karamanlis. The country was a member of NATO by now, and America continued to support the right winged government so that the communist would not be able to get back.

Once again, the question of Cyprus became a hot issue. The Greek Cypriots had wanted to unite with Greece in the 1930’s already, but Turkey had opposed to this. In 1925 the island had become a British crown colony, and in 1954 the British explained their intentions of making Cyprus an independent state. In 1959 Cyprus became an independent republic with the archbishop Makarios as president and a Turk as vice president. Internal hostilities continued between Turkish Cypriots and right wing Greek Cypriots.

CYPRIOT UNIONISTS OF EOKA

Post-Civil War Recovery and the 1950s

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Greece was a country deeply scarred by conflict, with its economy in ruins and its society divided. The government, supported by the United States through the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan, embarked on a path of reconstruction and attempted national reconciliation. The 1950s saw Greece making significant strides in economic recovery, aided by foreign aid and investment. Politically, however, the landscape was dominated by conservative forces, with the right-wing Greek Rally party under Field Marshal Alexandros Papagos, and later Constantine Karamanlis’s National Radical Union (ERE), playing pivotal roles. The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) was outlawed, and its members were persecuted, creating a legacy of division and mistrust.

The 1960s and the Rise of Centrism

The 1960s introduced a brief era of liberalization and an attempt to bridge the chasm left by the Civil War. George Papandreou’s Center Union party came to power in 1963, promoting policies aimed at social reform and greater political freedom. This period, however, was also marked by instability, with the assassination of left-wing politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963 and the subsequent political crisis that revealed deep divisions within the military and the monarchy.

The Civil War 1946-49

With the departure of the Germans from Greece, a government of National Unity was established in Athens with Georgios Papandreou as Prime Minister. King George II returned to Greece after the referendum of 1946, but died soon afterwards (April 1, 1947). He was succeeded by his brother Paul of Greece. In the meantime, a peace treaty was signed with Italy, according to which the Dodecanese was integrated with Greece.

During the period 1946-1949, the country was tested by the Civil War. In 1952 the country joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), from whose military wing it left after the occupation of Cyprus by Attila in 1974, but applied to rejoin and was accepted again in 1979. In 1964 King Paul I died and he was succeeded to the throne by his son Constantine II.

The Dictatorship 1967-1974

The period between 1967 and 1974 marks a dark chapter in the modern history of Greece, known as the Regime of the Colonels or the Junta. This was a time when democracy in Greece was abruptly halted by a military coup that led to a seven-year dictatorship characterized by oppression, censorship, and a significant rollback of civil liberties.

The coup d’état on April 21, 1967, was led by a group of middle-ranking army officers, with Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos emerging as the leading figure. The pretext for the coup was the political instability and social unrest that had gripped Greece for years. However, the real motive was to prevent the leftist forces from gaining power, amidst the Cold War tensions that saw the Eastern and Western blocs vying for influence in strategic locations, including Greece.

Once in power, the junta suspended the constitution, dissolved political parties, and arrested a large number of politicians, academics, journalists, and anyone suspected of being a leftist or a threat to the regime. The press was heavily censored, and all forms of political dissent were brutally suppressed. The regime justified its actions by claiming it was saving the nation from a communist threat and sought to “revitalize” the Greek nation through a return to traditional values based on the Christian Orthodox faith, the monarchy, and the family.

Despite the oppressive nature of the regime, the junta initiated several economic policies that led to substantial infrastructural development and a period of economic growth. However, these achievements were overshadowed by the widespread violation of human rights, including torture and exile for political prisoners, which drew international condemnation.

The dictatorship’s foreign policy was marked by a pragmatic alignment with the West, particularly the United States, which, despite initial ambivalence, supported the regime as a bulwark against communism in the Mediterranean. The junta’s attempt to annex Cyprus and enforce a union with Greece in 1974 led to a disastrous military invasion by Turkey, following a coup on the island aimed at achieving Enosis (union with Greece). This event precipitated the collapse of the junta, as the military regime found itself unable to defend Cyprus or maintain its grip on power amidst the national outrage and humiliation that followed.

In July 1974, the junta collapsed, and Konstantinos Karamanlis was invited back from exile to form a government of national unity and lead the country’s transition back to democracy. The fall of the dictatorship paved the way for the Metapolitefsi, Greece’s transition to democratic governance, the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of the Third Hellenic Republic.

The dictatorship period left a deep scar in the Greek social and political landscape, influencing the country’s politics and society for decades to come. The memory of the junta serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of democracy and the enduring need to safeguard freedom and human rights against the forces of authoritarianism.

The Polytechnic uprising

The Polytechnic Uprising took place in November 1973. This student-led demonstration against the military junta, which had seized power in Greece in 1967, became a symbol of resistance against dictatorship and a pivotal moment leading to the restoration of democracy in Greece.

The focal point of the uprising was the National Technical University of Athens, commonly known as the Polytechnic. In mid-November 1973, students began to gather at the Polytechnic, barricading themselves inside and broadcasting calls for resistance, democracy, and freedom via a makeshift radio station. The movement quickly drew support from a broad swath of Greek society, swelling into a massive demonstration against the junta.

The students’ demands included the restoration of democracy, the release of political prisoners, and the withdrawal of the military from politics. For several days, the Polytechnic became a beacon of resistance, with thousands of Athenians of all ages joining the students in solidarity. In the early hours of November 17, 1973, the military responded with brute force. Tanks rolled into central Athens, and one famously crashed through the gates of the Polytechnic. The exact number of casualties remains a matter of debate, with official figures underreporting the death toll. The crackdown brutally suppressed the uprising but also marked the beginning of the end for the military regime.

The Polytechnic Uprising did not immediately lead to the fall of the junta, but it significantly weakened the regime’s legitimacy both domestically and internationally. The event galvanized opposition to the dictatorship, leading to increased unrest. The regime attempted to appease public sentiment by announcing a transition to civilian rule, but its credibility was irrevocably damaged.

Greece after the military dictatorship

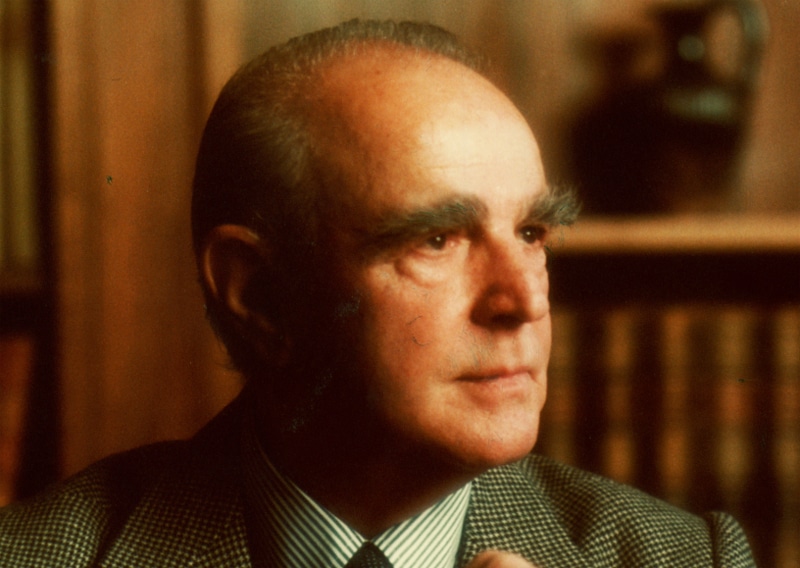

A government of national unity was formed with Konstantinos Karamanlis, who after the elections of November 1974 formed his own majority government. A referendum followed on 8th December 1974 which abolished the monarchy and Michail Stasinopoulos temporarily took over the presidency of the republic. He was succeeded by Konstantinos Tsatsos, in 1976. The elections of 1977 again gave the majority to the New Democracy party (Nea Democratia) under Karamanlis, who in 1980 succeeded Tsatsos in the presidency of the republic.

KONSTANTINOS KARAMANLIS.

The abolishment of Monarchy and the referendum of 1974

After the fall of the military regime, Constantine Karamanlis, a respected statesman and former prime minister, returned from self-imposed exile to head a government of national unity. His return was facilitated by the junta’s collapse and a widespread desire among the Greek population for stability and democratic governance. One of Karamanlis’s first actions was to address the contentious issue of the monarchy, which had become deeply unpopular due to King Constantine II’s early support for the 1967 coup that led to the military dictatorship.

To resolve the matter, Karamanlis proposed a referendum to decide the future of the monarchy in Greece. The referendum, held on December 8, 1974, was conducted in a climate of fervent public debate and widespread participation. The result was an overwhelming rejection of the monarchy, with approximately 69.2% of voters favoring the establishment of a republic. Only about 30.8% voted in favor of retaining the monarchy. This decisive outcome reflected a strong public sentiment against the monarchy, partly due to its association with political instability and its perceived complicity with the military junta.

The referendum’s result led to the formal proclamation of the Third Hellenic Republic on December 13, 1974. Constantine Karamanlis played a pivotal role in this transition, ensuring a peaceful and democratic shift from dictatorship to a parliamentary republic. The abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic marked a new era in Greek politics, characterized by democratic consolidation, political pluralism, and the stabilization of civil-military relations.

The 1974 referendum was not just a rejection of the monarchy but also a strong affirmation of democratic values by the Greek people. It was seen as a crucial step towards healing the divisions caused by the civil war, the military dictatorship, and the political turmoil of the previous decades. The establishment of the Third Hellenic Republic laid the foundation for Greece’s contemporary political system and its integration into the European and international community.

Greece in the European Union

Greece’s entry into the European Union (EU) marked a significant milestone in the country’s modern history, reflecting its longstanding orientation towards Europe and its aspirations for economic development, political stability, and integration into the European community. Greece became the tenth member of the European Economic Community (EEC), the precursor to the EU, on January 1, 1981, after years of negotiations and preparations that began in earnest in the 1970s following the restoration of democracy.

The application for EEC membership, initially submitted in 1975 under the government of Konstantinos Karamanlis, reflected Greece’s ambition to join a community that shared its values of democracy, freedom, and economic cooperation. The accession process was seen as a testament to Greece’s European identity and its commitment to participating in the project of European integration.

Greece’s accession to the EEC was not without challenges. The country had to undertake significant economic and regulatory reforms to align with the Community’s policies and standards, ranging from agricultural practices to industrial policy and environmental regulations. The transition required substantial adjustments within the Greek economy, which faced issues of competitiveness, productivity, and structural inefficiencies.

Despite these challenges, membership in the EEC offered Greece a platform for growth and modernization. It facilitated access to structural funds aimed at reducing economic disparities within the Community, which helped finance infrastructure projects, improve telecommunications, and support rural development. The European Single Market, established in 1993, further enhanced Greece’s economic opportunities by allowing the free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor.

1981 -2019

In the 1981 elections, PASOK emerged as the first party, led by Andreas Papandreou, who with a 48% majority formed an autonomous government. In the days of this government the National Resistance was recognized, civil marriage was established and the right to vote was established at the age of 18 years. After the defeat of PASOK in the elections of June 1989, a coalition government of N. Democracy- and the Greek Communist party was formed in October with X. Zolotas as president. After the elections of April 1990, the New Democracy came to power, with Konstantinos Mitsotakis as Prime Minister.

Christos Sartzetakis was elected president of the Republic in 1985 and in 1990 Konstantinos Karamanlis, supported by the New Democracy, returned. He was succeeded in 1995 by K. Stefanopoulos, who was supported by PASOK and POL.AN. In 1993, A. Papandreou was re-elected Prime Minister. Konstantinos Simitis succeeds A. Papandreou in the prime ministership in January 1996 and in the leadership of the party in July 1996. In the elections of September 22, 1996, PA.SO.K wins.

Later on, after the defeat of PASOK the Left party of Syriza won the Elections and ran the country between 2015-2019. However, the elections of 2019 saw the return of the New Democracy party led by Konstantinos.Mitsotakis

Karamanlis was called back to Greece by the army in order to organise the country, and his party won the elections of 1974. The son of George Papandreou, Andreas, formed the socialist party PASOK ( Panhellenic National Movement) and during these elections he got the 13.58% of the votes. At the referendum of 1974 69% of the people voted against reinstating the king, and the monarchy was banned. Ex-king Constantine still lives in exile in London.

Karamanlis’ Nea Demokratia party won the elections again in 1977, and four years later the country joined the EU. The same year 1981 PASOK won the elections with big majority and Papandreou promised that the American military bases in Greece would be shut down, and that Greece would leave NATO. These promises were never fulfilled. But Andreas Papandreou achieved many other things in Greece and became one of the most beloved political leaders of the country. He was accused, after the infamous “scandal of Koskotas”, but acquitted, of charges of embezzlement of the Bank of Crete.

ANDREAS PAPANDREOU

In 1996 Papandreou resigned due to ill health, and was succeeded by Costas Simitis, he leaded European friendly politics, and emphasized on modernisation of the country, improve its economy and fight corruption. During the 20 years of reign of the Greek Socialist Party PASOK under Papandreou and Simitis (with a break in 1990 when the conservative party won again, with Kostantinos Mitsotakis as leader, whom after a series of personal and political scandals resigned, and in 1993 PASOK won the new elections) Greece and the Greek Economy flourished.

Greece became a high developed country and the quality of life in Greece reached the levels of the other developed countries of the world. The highlight of this development and achievement was the Olympic Games of 2004. Andreas Papandreou together with Konstantinos Karamanlis and Eleftherios Venizelos where the greatest politicians in the History of Modern Greece.

Greece today

Greece’s cultural heritage is alive and well, celebrated in festivals, music, dance, and cuisine that reflect the country’s rich history and diversity. Traditional tavernas serve up mouthwatering dishes bursting with Mediterranean flavors, while lively bouzouki music fills the air in tavernas and cafes. From ancient ruins to Byzantine churches, Greece’s archaeological treasures offer glimpses into the past, while modern museums and galleries showcase the country’s vibrant arts scene.

In the realm of commerce and innovation, Greece is carving out a niche as a hub for technology, entrepreneurship, and sustainable development. Startups and tech companies are flourishing in cities like Thessaloniki and Patras, while initiatives aimed at promoting renewable energy and environmental conservation are gaining momentum. Greece’s strategic location at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa positions it as a key player in regional trade and cooperation.

Despite the challenges of recent years, including economic uncertainty and geopolitical tensions, Greece’s spirit remains indomitable. Resilient and resourceful, Greeks are embracing the future while cherishing their past, forging a path towards a brighter tomorrow. As the sun sets over the Aegean Sea, casting a golden glow on ancient ruins and modern skylines alike, one thing is clear: Greece’s timeless allure will continue to captivate the world for generations to come.

City Life

Urban areas have become increasingly impersonal, with the sense of close-knit neighbourhoods that were so common before the 1970s being drastically diminished due to development and the tendency of families to replace their traditional single storey family homes with an apartment in apartment blocks which are usually a single flat comprising of two or three rooms.

The transition from a house with its own small garden and jasmine plants to one or two apartments in an apartment block is embodied in old Greek films as ageless reminders of days gone by which evoke nostalgic memories for many people.

Most families possess at least one car, often more. Unfortunately, when the apartment blocks were constructed, not much attention was given to supplying adequate parking spaces; meaning that streets have become filled with double-parked cars.

As a consequence of this, scenes of children running around and mothers sitting outside their homes while catching up with their neighbours has transformed into a rarity only in the Greek provinces and villages. To alleviate this issue, cities now provide pleasant squares ( mostly build up by ciment with a small kindergarden) which give children an area to explore safely, if they are accompanied by an older child or adult. Not only do these squares act as a safe haven for young ones; they are also points where citizens gather; typically surrounded by eateries, cafeterias, bars and fast food outlets.

Overview of Modern Greece

Greece’s economy has faced significant challenges in recent years, particularly due to the global financial crisis and the country’s debt crisis. However, the government and international institutions have implemented measures to stabilize the economy, and Greece has shown signs of recovery. Tourism, shipping, agriculture, and manufacturing are important sectors for the Greek economy.

Culture and Lifestyle

Greeks are known for their warm and hospitable nature. Family plays a central role in Greek society, and social gatherings often revolve around food, music, and lively conversations. Traditional Greek cuisine, with dishes like moussaka, souvlaki, and baklava, is popular both within Greece and internationally. Greek Orthodox Christianity is the predominant religion, and religious festivals and traditions are an integral part of Greek life.

Tourism

Greece is a popular tourist destination, attracting millions of visitors each year. The country offers a diverse range of attractions, including ancient ruins, picturesque islands, stunning beaches, and vibrant cities like Athens and Thessaloniki. The tourism industry plays a crucial role in the Greek economy, and many Greeks are employed in this sector.

Education and Healthcare

Greece has a well-developed education system with both public and private institutions. Higher education in Greece is highly regarded, and there are several universities and technical colleges throughout the country. Regarding healthcare, Greece has a national healthcare system that provides universal coverage to its citizens and legal residents.

Infrastructure

Greece has made significant investments in infrastructure development, particularly in transportation. Major cities are well-connected by roads, airports, and ports. Public transportation, including buses and trains, is available in urban areas. However, it’s worth noting that the quality and efficiency of infrastructure can vary across different regions of the country.

The financial crisis of 2009

Greece experienced a severe financial crisis starting in 2009, which had significant implications for its economy and the broader European Union. Here are some key points about the Greek financial crisis:

-

Causes:The Greek financial crisis had multiple causes, including high levels of government debt, unsustainable public spending, weak tax collection, corruption, and economic mismanagement. Greece’s entry into the Eurozone also played a role, as it allowed the country to borrow at lower interest rates, leading to excessive borrowing.

-

Bailouts: To prevent a potential default and stabilize Greece’s economy, the country received financial assistance from international lenders, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the European Commission. Three bailout programs were implemented in 2010, 2012, and 2015, providing loans in exchange for implementing structural reforms and austerity measures.

-

Austerity Measures: As part of the bailout agreements, Greece implemented extensive austerity measures to reduce public spending, increase taxes, and reform its economy. These measures aimed to address budget deficits, reduce public debt, and improve competitiveness. However, they also led to significant social and economic challenges, including high unemployment rates and reduced public services.

-

Economic Consequences: The Greek financial crisis had a profound impact on the country’s economy. Greece experienced a deep recession, with GDP contracting significantly, unemployment rates soaring, and businesses closing down. The crisis also resulted in social unrest and political instability.

-

Debt Restructuring: In 2012, Greece underwent the largest sovereign debt restructuring in history, with private creditors accepting significant losses on their holdings of Greek government bonds. This debt restructuring aimed to reduce Greece’s debt burden and make it more sustainable.

-

Ongoing Challenges: Despite the bailout programs and debt restructuring, Greece continues to face economic challenges. High levels of unemployment, particularly among the youth, and a burdened public sector are ongoing concerns. However, there have been some signs of economic recovery in recent years.

It’s worth noting that the situation in Greece may have evolved since my last knowledge update in September 2021. For the most up-to-date information on Greece’s financial situation, I recommend referring to reliable news sources or conducting further research.

Economy, politics and social issues

In terms of the economy, Greece has faced significant challenges in recent years, particularly due to the global financial crisis and its subsequent debt crisis. However, the country has implemented various economic reforms and received financial assistance from international institutions, which have helped stabilize the situation to some extent. Tourism, agriculture, shipping, and services are important sectors contributing to the Greek economy.

Greece also faces certain social and political issues. Unemployment rates, especially among the youth, have been relatively high, although there have been improvements over time. The government has been working on addressing these challenges through job creation initiatives and reforms.

Regarding healthcare and education, Greece has a universal healthcare system, and education is considered a fundamental right. The country has made efforts to improve the quality of education and enhance access to healthcare services.

Cultural aspects today in Greece

Culturally, Greeks place great importance on family, food, and socializing. Festivals, religious celebrations, and traditional events are an integral part of Greek life. Greek cuisine is renowned for its Mediterranean flavors, with dishes like moussaka, souvlaki, and tzatziki being popular.

It’s important to note that the situation in Greece may have changed, especially given the global events and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. For the most accurate and up-to-date information, I recommend consulting trusted sources such as official government websites or recent news outlets

The end of an Era

The traditional kafenion, the place where older men in particular would meet up for ouzo or coffee and a game of backgammon have almost disappeared. They are now relegated to the back streets of neighbourhoods and can be quite difficult to find. For a taste of what Athens used to be like before these changes watch one of the old black and white Greek films made in the 1950s and 1960s.

Watching one of these old Greek films the first thing that strikes you after you have got over the lack of traffic on the roads, the clear unpolluted atmosphere and the smallness of the cityscape, is the simplicity of the life and the much lower standard of living than that which Greeks enjoy today.

The change of the city life in Greece

Arguably, there are two reasons for the change of the city life in Greece. Firstly, in Greece today, around one third of the population live in Athens. This demographic change first began in the 1950s with economic push/pull factors.

The villages and provinces, at this time, gave few opportunities for employment for young people; the way of life was hard and difficult when compared to Athens. Secondly, especially today, the increase in living standards has played a role in alienating people from each other.

Having more consumer durables and luxury items to buy has meant that people need to work longer hours, often in two different jobs, in order to pay for these things.

The young Greek adult generation today

The young Greek adult generation in their twenties and thirties are impeccably turned out. Extremely fashion and label conscious. Greek young men want and buy the latest top of the range expensive car and/or motorbike. These then become status symbols that assist them in their parade around the squares – with expensive sound systems installed in their cars to ensure that they are noticed.

There has developed a certain snobbery about living in the city, especially Athens, as if by doing so you are automatically more sophisticated, more intellectual, more educated.

Yet nearly every Athenian citizen has a family and their roots either on an island or somewhere in the Greek countryside of the mainland and, in the summer especially in August, they flock back ‘home’ like migrating birds for the celebration of Panagia (Holy Mary) in the 15th of August. just like they do in the Greek Easter holidays.

For the Greeks in the big cities the jolly outing starts on Friday and Saturday night mostly in Restaurants ,and later on (the younger ones) in cinemas ,bars clubs or live music shows. Sundays are the best for daily excursions in the country side with a traditional lunch at a Greek Tavern with grilled lamb and kokoretsi or fresh fish with ouzo and meze if they are in a seaside resort. Sunday is also a great day for the football funs with a day in the football stadium especially if is a big much between their local team and a guest team. The Greek television though ,unfortunately has taken over the 30% about of the life of an average Greek .

Economic Recovery and Challenges

One of the most pressing issues facing Greece in recent years has been its economic struggles. The country endured a severe financial crisis starting in 2009, marked by soaring debt levels, high unemployment rates, and stringent austerity measures imposed by international lenders. While Greece has made significant progress in stabilizing its economy and implementing structural reforms, the legacy of the crisis still lingers. Youth unemployment remains stubbornly high, and many Greeks continue to grapple with economic insecurity. However, there are signs of hope on the horizon, with Greece’s economy showing signs of recovery and renewed investor confidence in recent years.

Cultural Resilience and Heritage

Despite its economic challenges, Greece remains a global beacon of culture and civilization. The country’s rich heritage, encompassing ancient Greek mythology, philosophy, and art, continues to captivate and inspire people around the world. From the iconic Parthenon in Athens to the stunning sunsets of Santorini, Greece’s cultural landmarks draw millions of visitors each year, contributing significantly to the country’s tourism sector. Moreover, Greece’s vibrant cultural scene, encompassing music, literature, and gastronomy, reflects the resilience and creativity of its people in the face of adversity.

Geopolitical Dynamics and Regional Cooperation

As a strategic crossroads between Europe, Asia, and Africa, Greece plays a pivotal role in regional geopolitics. The country’s location at the nexus of the Mediterranean and Aegean seas has historically made it a center of trade, commerce, and cultural exchange. Today, Greece faces complex geopolitical challenges, including tensions with neighboring Turkey over maritime boundaries and migration flows. However, Greece also seeks to leverage its geostrategic position to promote stability and cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean region. The recent establishment of the 3+1 mechanism, bringing together Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and the United States, underscores Greece’s growing role as a key player in regional affairs.

Environmental Sustainability and Climate Change

Like many countries around the world, Greece is grappling with the urgent challenges of environmental sustainability and climate change. The country’s unique natural beauty, including its pristine beaches, rugged mountains, and lush forests, is under threat from pollution, deforestation, and the impacts of climate change. Rising temperatures and changing weather patterns pose risks to Greece’s agricultural sector, which forms the backbone of many rural communities. However, Greece is also taking steps to address these challenges, with initiatives ranging from renewable energy development to coastal protection measures aimed at preserving its natural heritage for future generations.

Social Cohesion and Community Resilience

Amidst the complexities of modern life, Greece’s social fabric remains a source of strength and resilience. The concept of “philoxenia,” or hospitality, is deeply ingrained in Greek culture, fostering strong bonds of community and solidarity. In recent years, grassroots initiatives and civil society organizations have emerged to address pressing social issues, from poverty and homelessness to refugee integration and healthcare access. These efforts highlight the capacity of Greek society to come together in times of need and chart a path towards a more inclusive and equitable future.