The Hellenistic period of Greece

Hellenistic is the historical period of Greece defined by the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. until the naval battle of Aktio in 31 BC. The territories conquered militarily by Alexander and formed the political and cultural sphere of influence of the successors included except Greece, Syria and Palestine, Egypt and Libya and all the lands of the Near East that belonged to the former Persian Empire.

The end of the Hellenistic era coincides with the fall of the kingdom of Ptolemy and the annexation of Egypt to the Roman Empire. However, for many historians this is only a conventional, politico-military limit of the Hellenistic period, as “Hellenism”, now in the form of Greco-Roman civilization, continued to determine for many centuries the physiognomy of the world until late antiquity.

In the Alexandrian years’ territories, populations, the scale of business and profits were enormous. This gigantism, unprecedented in Greek history, which until then was subject to moderation, is manifested, positively or negatively, in the entire physiognomy of the era. Thus, in the 3rd BC century, the Colossus of Rhodes was erected, 32 meters high. In the 2nd BC. century, the altar of Pergamon was built on 1250 square meters. Hieron of Syracuse built a huge ship, so big that it could only fit in the port of Alexandria.

Likewise, the historian Diodorus Siculus wanted in his historical library to expose the entire world history in forty books from prehistoric times to his own day.As is often the case, these very phenomena (immensity, polyhumanity, gigantism) provoked reactions that quickly led to opposites: in those same years.

The micro-craftsmanship created marvelous jewelry, statuettes, cups, lamps, and other small objects; often poets expressed themselves in couplet epigrams; historians, when not writing world history, confined themselves to monographs about their locality; tired of the crowding and bustle of the cities, the townspeople sought open nature, forests, mountain slopes, and fields. For the first time, painters and sculptors depicted the natural environment with emphasis, while, correspondingly, in bucolic poetry, they were presented in their familiar space and the shepherds were the protagonists.

The turn to the countryside and the idealization of its inhabitants is a movement of flight from reality, but this does not prevent the era from generally favoring realism. Neither archaic nor classical art, each for different reasons, sought to render man and the world around him faithfully, realistically, with his beauty but also with his ugliness, in his good times as well as in his bad. Now artists attempted it. New Comedy is realistic. The mimes and other ethnographic works are realistic.

The same trend can be seen in the visual arts, where the old fisherman, the peasant woman with her baskets, the children, the drunken old woman with the wine jug, the hunchback, the slave, and the tramp, became favorite subjects, such as the pain, the death of the warrior and other analogies, which until then artists avoided depicting. We understand that the artists of the Hellenistic era chose subjects that until then had been left on the sidelines. In general, it was not at all easy for them to compete with the famous craftsmen of the Classical era. In order not to be overwhelmed, they could choose between two possibilities: either to follow the classical standards, or to look for subject areas and forms that the classical masters had for some reason neglected.

Most preferred the second, but there were also those who chose the path of imitation, artists and writers who did not hesitate to copy or, better, to recycle anything old and successful. Thus, a phenomenon that would later dominate, classicism, appeared for the first time in the Hellenistic years, i.e., the attempt for artists to create works of high art following classical standards.

Classicism presupposes not only admiration for older works but also deep knowledge of their content and form. This helps us to understand another characteristic of the time, the interest in and care for cultural heritage. The successors of Alexander the Great intensively cultivated letters and the arts in their courts, and founded museums and libraries, where almost the entire previous scientific and literary production was gathered, classified and studied. Most of the writers, scholars and scientists of the time gathered around them, worked and were richly rewarded.

The Hellenistic society

Hellenistic society was multi-ethnic and multicultural. The Greek cultural presence was strong, but the Hellenizing foreigners were not only influenced by Hellenism, but also influenced it. The Greek language dominated as a means of communication, as it was now learned and used as a common language by many peoples, but it also lost a part of its morphological richness and musicality through attrition.

In religion, the Greek gods became known and worshiped in Asia and in Egypt.

However, at the same time foreign gods, such as Isis and Osiris from Egypt, Attis from Phrygia, etc., were claimed to have Greek believers. They owe their success largely to the oriental mystical nature of their worship. The Hellenistic era, with its increased fears and great opportunities, favoured the mystical cults, which in a way calmed the fears and strengthened the hopes for bliss, if not in this life, at least in the afterlife. A common phenomenon was theocracy: Greek and foreign related gods were identified, their names were combined and the faithful recognized a god Zeus-Savazio, Hermes-Anubis, Sarapi-Pluto, etc.

In general, religious faith receded in the Hellenistic era. The tributes may have been richer and the temples grander, and the public worship may have seemed more luxurious than ever, but deep down the wealth and instability of the age had shaken the foundations of both morality and religion. The metaphysical needs of the people, when they were not met by the mysterious cults, were satisfied by so-called superstitious practices, such as spells, amulets, magic in general, and even by astrology and divination in its various forms. Only one goddess saw her cult being upgraded during those years: the goddess Tychi.

A characteristic phenomenon of the time was also the massive apotheosis. The alleged exaltation of a mortal, usually a ruler, to the rank of gods, the construction of temples dedicated to his worship, the offering of sacrifices, etc., were common phenomena in the East, but not in Greece, where the corresponding testimonies are few and doubtful.

Only after Alexander the Great, who while still alive claimed to be the son of Ammon-Zeus and had divine honours. His successors, the Seleucids, the Ptolemies and the Attalids, not only claimed to be descended from gods but also took care to be deified when they died. Sometimes this deification included their wives too, for their greatness and for their benefit to the country.

With these facts, the deifications were not based on religious faith but on political decisions that were intended to strengthen the prestige of the dynasty.

As for the moral order: all kinds of swindlers, courtesans, brokers, shameless talk, and the physical abuse and exploitation of slaves, all that was once considered marginal and reprehensible, seem now to be commonplace and a natural phenomenon of everyday life. Texts and archaeological findings testify that Hellenistic society, at least in the urban centres, where every deviant and marginalised of the world lived, could easily be characterized as indulgent, immoral, wasteful, ruthless, etc. – but of course similar characterizations, from wherever derived, are often exaggerated, if not unfair.

The great progress in the positive sciences also overturned the prevailing religious conceptions. Through their philosophical pursuits, the educated discover a world full of order, consistency and meaning. The idea that the ruler must serve the state and its people is also reflected in the context. The wider popular strata look to religion as a means of salvation. In this age of leaps and bounds, they place their expectations on Fortune, the goddess of coincidences, in the mystical and eastern cults.

Hellenistic Art and Culture

The spirit of the time is reflected in the art and architecture of the Hellenistic period. Art now more than ever has a secular character and focuses on topics from everyday life but also from the world of Dionysus and Aphrodite, with idyllic or dramatic content. In sculpture, the realism and rendering of the individual characteristics of the figures replaces the ideal beauty and the eternal youth.

The cities, founded by Alexander the Great and his successors, are developed in symmetrical rectangular squares, as suggested by the Milesian city planner and philosopher Hippodamos. Huge temples and galleries, altars with monumental scales and facades, luxurious burial buildings, theaters are built in public places and sanctuaries. They testify to the tendency to show power and wealth on the part of their founders and contractors. The rhythms and individual elements for their rich decoration do not obey the strict rules of the classical era.

Hellenistic art and architecture refers to the artistic and architectural styles that emerged during the Hellenistic period, which spanned from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the establishment of the Roman Empire in the 1st century BCE. This period witnessed a fusion of Greek culture with the influences of the conquered territories and diverse cultures within the vast empire.

Overall, Hellenistic art and architecture marked a departure from the strict conventions of Classical Greece, embracing more emotional and realistic expressions. It incorporated diverse influences and created a rich visual language that laid the foundation for later artistic and architectural developments.

The common denominator of all the works of art of the time is the love of the rulers of the time for the grand and the pompous. For this reason, huge building complexes and monumental constructions are erected with a mood for theatricality and sensationalism and an attempt to highlight human intervention in the natural environment.

Hellenistic architecture is characterized by the monumental facades of places and buildings, such as the gates of cities, the porticoes of markets and sanctuaries, the scenery of theaters and the entrances of burial monuments.

A special feature of these constructions is that both their dimensions and their decoration, which are formed independently of the architectural type of the buildings they frame or join. They combine traditional forms with luxury, high aesthetics and elaborate decoration. The Ionic style prevails everywhere, since the high and slender proportions of the Ionic columns, combined most of the time with the elaborate Corinthian capitals, best serve the decorative requirements of the Hellenistic artists.

At the same time, the use of the arch and the arch to house buildings, doors or gates became general, especially in Macedonia and Asia Minor. Huge temples and arcades, altars with monumental staircases and facades, luxurious burial buildings, theaters, luxurious residences etc. are built in public spaces and sanctuaries. and all are decorated with works of sculpture, whose themes the artists derive from the tradition of the classical era.

Hellenistic Art

The most common materials used in Hellenistic art were marble and bronze, although other materials such as terracotta and glass were also used. Hellenistic artists were known for their technical skill and attention to detail, as well as their ability to capture emotion and movement in their works.

One of the most iconic examples of Hellenistic art is the sculpture of Nike (Victory) on the island of Samothrace, which was created in the late 2nd century BC. The statue shows Nike with outstretched wings, her garments billowing in the wind, and is considered one of the finest examples of Hellenistic sculpture.

Another important aspect of Hellenistic art was the development of new subject matter. Hellenistic artists began to explore more complex themes, such as the human condition, mythology, and everyday life. They also began to depict events and individuals from outside the Greek world, reflecting the global reach of Alexander’s conquests.

Hellenistic art was characterized by a sense of drama and theatricality, as well as a focus on realism and individualism. Artists often depicted subjects with intense expressions and elaborate hairstyles, and were known for their intricate details and use of light and shade.

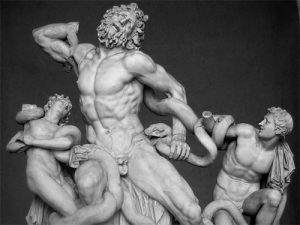

Overall, Hellenistic art represents a significant evolution in Greek art and culture, and remains an important influence on art and aesthetics today. Many famous works of Hellenistic art, such as the Venus de Milo and the Laocoön and His Sons sculpture, continue to attract visitors from around the world and inspire new generations of artists and art lovers.

Hellenistic sculpture

Portraiture Portraits became increasingly popular during the Hellenistic period. These sculptures aimed to capture the individuality, personality, and even psychological traits of the subjects. Portraits were highly realistic, displaying specific facial features, expressions, and even age-related characteristics. The “Head of an Old Man” from the Capitoline Museums in Rome is an example of Hellenistic portraiture.

Architectural Sculpture Hellenistic architecture incorporated sculpture as an integral part of the structures. Elaborate friezes, pediments, and reliefs adorned the facades of buildings. These sculptures often depicted mythological scenes, battles, and historical events. The “Great Altar of Pergamon” is a notable example of architectural sculpture.

Hellenistic mosaics

Mosaics depicted a variety of subjects such as mythological scenes, landscapes, and daily life. The “Alexander Mosaic” found in Pompeii is a renowned example of Hellenistic mosaic art.

During the Hellenistic period, mosaic art flourished and became a popular way of decorating public buildings, private homes, and even tombs. The mosaics were often made with small pieces of colored glass, marble, or other types of stone, and arranged in intricate geometric or floral patterns.

One of the most famous examples of Hellenistic mosaics is the Alexander Mosaic, which depicts the Battle of Issus between Alexander the Great and the Persian king Darius III. The mosaic was created in the 2nd century BC and was discovered in Pompeii in the late 19th century. Today, it is on display at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Hellenistic mosaics were also used to depict scenes from mythology or everyday life. These mosaics were often incredibly detailed, depicting people, animals, and objects with great accuracy and naturalism. Some famous examples of Hellenistic mosaics include the mosaic floors found in the House of the Faun in Pompeii and the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily.

The techniques of Hellenistic mosaic-making were highly skilled and developed, and required great care and attention to detail. Mosaic artists had to spend a great deal of time arranging the tesserae to create the desired effect, and often used different materials and colors to achieve a particular effect.

Overall, τηε mosaics represent an important aspect of ancient Greek art and design, and continue to inspire awe and admiration for their beauty and technical achievement. Many examples of Hellenistic mosaics can be found in museums and archaeological sites throughout the Mediterranean region, offering a glimpse into the ancient world and the skill of its artists

Hellenistic Architecture

One of the most iconic examples of Hellenistic architecture is the Library of Alexandria in Egypt, which was built in the 3rd century BC. The library was designed to be a center of learning and contained over half a million manuscripts from around the world. The building was adorned with intricate decorations and was one of the largest and most impressive libraries of the ancient world.

Another notable example of Hellenistic architecture is the Acropolis in Athens, which was built during the 5th century BC but was later reconstructed and modified during the Hellenistic period. The complex contains several famous structures, including the Parthenon, the Propylaea, and the Erechtheion.

Hellenistic architects were known for their use of new materials, such as marble and limestone, as well as their attention to detail and design. They incorporated elements of previously established architectural styles, such as the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders, but also introduced new ideas, such as the use of columns with spirals, twisted fluting, and elaborate capitals.

One of the most important innovations of Hellenistic architecture was the use of monumental scale. Builders began to create massive structures that were designed to impress and awe viewers with their grandeur and magnificence. They also experimented with new forms of structural engineering, such as the use of arches and vaults to create larger and more complex buildings.

Overall, Hellenistic architecture represents a significant evolution in Greek architectural style and remains an important influence on architecture and design today. Many famous structures, such as the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, continue to inspire awe and admiration for their beauty, complexity, and technical achievement.

Theatres

Hellenistic period saw the development of large-scale theatres with improved acoustics and seating arrangements. The theatres had a semi-circular seating area called the auditorium, which was carved into the side of a hill. The Theatre of Epidaurus in Greece is an excellent example of Hellenistic theatre architecture.

Hellenistic temples

Hellenistic temples were a distinctive style of temple architecture that emerged during the Hellenistic period, which spanned from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the conquest of Egypt by the Romans in 30 BCE. These temples were built in various parts of the Hellenistic world, including Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor, and the Near East. Here’s some detailed information about Hellenistic temples:

-

Architectural Features: Hellenistic temples continued the tradition of Greek temple architecture but incorporated new elements and decorative motifs. They typically followed the classical Greek temple plan, consisting of a rectangular cella (inner chamber) surrounded by a colonnaded portico. The most common column order used was the Corinthian, characterized by its elaborate capitals adorned with acanthus leaves.

-

Increased Size and Complexity: Hellenistic temples were often larger and more elaborate than their classical Greek counterparts. They featured expanded colonnades and more intricate architectural ornamentation. The increased scale was partly due to the wealth and power of Hellenistic rulers who sponsored these grand construction projects.

-

Fusion of Architectural Styles: Hellenistic temples incorporated influences from various cultures and architectural traditions. As a result, you can find a fusion of Greek, Egyptian, Persian, and other Eastern elements in the design. For example, some temples featured Egyptian-style pylons (gateway structures) at the entrance or incorporated Egyptian motifs like sphinxes and lotus flowers.

-

Use of Mixed Materials: Hellenistic temples employed a wide range of building materials, including local stone, marble, and even imported precious stones. They often combined different types of stone, creating a visually striking effect. Sculptures and reliefs were also commonly used to decorate the exteriors and interiors of these temples.

-

Monumental Staircases and Terraces: Hellenistic temples were frequently situated on elevated platforms or terraces, accessed by monumental staircases. These staircases served both functional and symbolic purposes, emphasizing the grandeur and importance of the temple. The terraces provided additional space for processions and ceremonies.

-

Integration with the Surrounding Landscape: Hellenistic temples were designed to harmonize with their natural surroundings. They were often located in prominent locations, such as hilltops or near water bodies, creating a visually striking impact. The architecture and placement of these temples aimed to evoke a sense of awe and reverence in visitors.

-

Regional Variations: While Hellenistic temples shared common features, regional variations can be observed. For example, in Egypt, Hellenistic temples often incorporated elements of traditional Egyptian temple design, such as hypostyle halls and colossal statues of deities. In Asia Minor, the temples exhibited a more eclectic mix of Greek and Anatolian influences.

Notable examples of Hellenistic temples include the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, the Temple of Apollo at Didyma in Turkey, and the Temple of Horus at Edfu in Egypt. These temples stand as impressive architectural achievements that reflect the cultural and artistic exchange of the Hellenistic period.

Palaces and Royal Structures

The Hellenistic period witnessed the construction of grand palaces and royal structures. These buildings were often adorned with ornate decorations and sculptures. The Pergamon Palace in Turkey, with its impressive terraces and monumental staircase, exemplifies Hellenistic royal architecture.

Urban Planning

Hellenistic cities were often planned on a grid system, with wide streets and monumental public buildings. The city of Alexandria in Egypt is a notable example of Hellenistic urban planning, with its grand buildings, harbor, and famous lighthouse, the Pharos of Alexandria.

The characteristics of the Hellenistic world

Trade and finance.

The overthrow of the Persian Empire and the spread of Hellenism in the East were followed by significant changes in the economic sector, which subsequently affected the structure of the Hellenistic kingdoms. The Hellenistic world, Greeks and foreigners, operated within a single economic system. The main economic elements concerning the Greek city-states and the Persian Empire, were merged through the use of a common monetary system, a common fiscal policy and a common way of trading.

The kings owned all the land and most of the produce. The rich agricultural production and the exchange of the produced goods between the kingdoms opened new horizons in the trade. Greek coins were used to facilitate transactions and Persian ones were withdrawn. At the same time, banks were created and checks were used.

Those who engaged in trade and banking, but also those who exercised power as royal servants, formed a privileged class, a bourgeois * class consisting mainly of Greeks and a few Hellenizing natives. Most of the natives were workers and small farmers who gathered in the big cities in search of better fortune. Within this system of economic relations the development of slavery was favored. Where there was not enough free labor, slaves were used. The dependent slave-labor work that prevailed in the East, although not abandoned, was no longer sufficient to meet the needs of the affluent living of the rulers and the upper classes. These needs were met mainly by the use of slaves

Politics during the Hellenistic period

The system of government in the Hellenistic kingdoms was the absolute monarchy. The rulers gathered in their person all the powers and ruled with a staff of Greeks and a few natives who belonged to higher economic strata and had become Hellenized. The glamor of the rulers was increased by the worship attributed to them by the subjects. In this system of absolute monarchy the citizen had no role to play, he was only interested in his individual interest. External Link

The center of gravity shifted from metropolitan Greece to the major cities of the East (Alexandria, Antioch, Pergamon and others), which were the administrative, economic and cultural centers of the Hellenistic world.

The Greek area was governed according to the standards of the Macedonian kingdom. Some city-states (Athens, Sparta, Rhodes, Delos and others), however, maintained their autonomy, often obeying the wishes of the kings. Other areas of Greece to maintain their autonomy were organized into federations, as happened with the Aetolians and the inhabitants of Achaia.

Following Alexander’s death, his generals, known as the Diadochi, engaged in a series of wars, called the Wars of the Diadochi, to establish their own regional kingdoms. These Diadochi fought among themselves and sought to legitimize their rule by claiming to be successors to Alexander.

The Wars of the Diadochi

The Wars of the Diadochi resulted in the division of Alexander’s empire into several Hellenistic kingdoms, each ruled by a Diadochi or their descendants. The most prominent Hellenistic kingdoms were the Seleucid Empire in Asia, the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt, and the Antigonid Kingdom in Macedon and Greece. These kingdoms adopted Greek political institutions and spread Greek culture, but they also incorporated local customs and practices to maintain stability and govern diverse populations.

Hellenistic kingdoms

The Hellenistic kingdoms were primarily monarchies, with the ruling families claiming descent from Alexander or his generals. These kings held absolute power and were often regarded as divine or semi-divine figures. They relied on a centralized bureaucracy to govern their vast territories, employing officials and administrators to manage affairs on a local level.

Greek Polis Influence

While the Hellenistic kingdoms were monarchies, they also retained some aspects of Greek city-state (polis) politics. The polis continued to exist in some regions, albeit with reduced autonomy. Greek cities served as centers of culture, education, and commerce. They often enjoyed a degree of self-government but were subject to the authority of the Hellenistic kings.

Cosmopolitanism

The Hellenistic period witnessed increased cultural and intellectual exchange, resulting in a cosmopolitan society. Greek philosophy, literature, and art flourished during this time, influenced by the diverse cultures of the Hellenistic kingdoms. Cities like Alexandria in Egypt became renowned centers of knowledge and scholarship.

Hellenistic League

The Hellenistic League was an alliance of Greek city-states formed in 224 BCE to counter the expansionist ambitions of Macedon. It aimed to preserve Greek autonomy and protect Greek culture. However, it eventually fell under the dominance of Macedon and lost its significance.

Roman Influence

Towards the end of the Hellenistic period, the Roman Republic began to exert its influence over the Hellenistic kingdoms. Rome gradually expanded its control, leading to the eventual conquest and absorption of these kingdoms into the Roman Empire.

Hellenistic Literature

During Hellenistic times, the mass production of books was facilitated for the first time. The spread and widespread use of writing materials, such as papyrus and parchment, and the creation of intellectual centers, such as the libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum, contributed in this direction. However, the large production of books is not associated with a corresponding richness in their content.

The authors were mostly imitators of works of the classical era. Still other intellectuals concerned themselves only with gathering the work of writers of earlier ages. In the libraries they copied and commented on the texts of the classics. They were the first philologists and were called grammarians.

Poetry presented no great works in terms of originality and inspiration. Many poets were paid cronies of the powerful. Their poems praised the persons and deeds of kings, as was the case with Callimachus in Alexandria. Others were imitators of older poetic genres, such as the heroic epic.

Such a work was the “Argonautica” of Apollonius of Rhodium, based on the myth of the Argonautic expedition. More originality distinguished Theocritus, who with his work “Idylls” became a proponent of bucolic poetry. A new poetic genre, also with satirical speech, are the “Mimes” written by Herondas.

At this time it was cultivated the epigram and of the theatrical genres only comedy. The new comedy, as it was called, satirized human characters. Its subject was the everyday man with his flaws. Its main representative was Menandros.

The the study of historical writing, towards the end of the Hellenistic years, has to present a historical family of those classical times. Polybius the Megalopolitan lived during the times of Roman expansion. For seventeen years he stayed in Rome as a hostage and socialized with important persons, such as those of the Scipio circle. He writes the history of his time and tries to explain to his contemporaries the reasons for the dominance of the Romans.

Athens, although it is in economic and political withering, is still during the Hellenistic times an intellectual center to which students come from various places mainly to be taught philosophy. In addition to Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum, two new schools of philosophy operate. Philosophical thought focused its interest on problems concerning human life. Get practical and ethical content.

The problem of the value of life occupied Zeno. The seat of his philosophical school was the Diverse Stoa in the ancient market of Athens, which is why Zeno’s teaching was called Stoic philosophy. According to his views, life has little value, so man must be self-sufficient and temperate. According Zeno happiness does not depend on earthly things.

At the opposite end was Epicurus, who had the headquarters of his school in an idyllic area of Athens called Kipos (garden). He taught that knowledge of nature helps man get rid of fear and ensure peace of mind. Only with spiritual, mainly, enjoyment is it possible for man to be led to happiness.

Urban planning

Hellenistic urban planning refers to the principles and practices of city design and organization during the Hellenistic period, which spanned from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE. This era witnessed the spread of Greek culture and influence throughout the eastern Mediterranean and beyond, resulting in the establishment of numerous cities that reflected Greek architectural and planning ideals.

Hellenistic urban planning was characterized by several key features:

-

Gridiron street layout: Hellenistic cities often featured a gridiron street pattern, with streets intersecting at right angles. This organized layout provided a sense of order and facilitated ease of movement within the city.

-

Centralized core: Hellenistic cities typically had a central core or acropolis that served as the focal point of the urban design. This core area often contained important civic and religious structures, such as temples, theaters, and administrative buildings.

-

Public spaces: Public spaces played a significant role in Hellenistic urban planning. Cities featured open squares or agora, which served as bustling marketplaces and meeting places for social and political activities. These areas also hosted cultural events and public gatherings.

-

Monumental architecture: Hellenistic cities were known for their impressive architecture, with monumental buildings and structures dotting the urban landscape. These included temples, theaters, gymnasiums, and libraries. The buildings were designed to showcase the wealth, power, and cultural sophistication of the city.

-

Connectivity: Hellenistic cities were often strategically located near trade routes and harbors, emphasizing their connection to regional and international trade networks. This allowed for economic growth and cultural exchange, as well as the integration of diverse influences into the urban fabric.

-

Water management: The provision of water was a crucial aspect of urban planning in the Hellenistic period. Cities employed advanced hydraulic engineering techniques, such as aqueducts, cisterns, and drainage systems, to ensure a reliable water supply for domestic use, irrigation, and public fountains.

-

Residential areas: Hellenistic cities typically had distinct residential neighborhoods, which varied in their socio-economic composition. Wealthier residents often lived closer to the city center, while poorer inhabitants resided in the outskirts.

One notable example of Hellenistic urban planning is the city of Alexandria in Egypt, founded by Alexander the Great. Alexandria incorporated many of the features mentioned above, including a gridiron street layout, a monumental central core featuring the famous Pharos Lighthouse and the Great Library, and the inclusion of public spaces like the agora and the Royal Gardens.

Overall, Hellenistic urban planning aimed to create well-organized, aesthetically pleasing, and functional cities that reflected the cultural and political ideals of the time.

The kingdoms of the East

When Alexander conquered Egypt, he was proclaimed pharaoh and when he overthrew the Persian Empire, he ascended the throne of the Achaemenids and ruled over many peoples. Thus the kingdom became personal.

his type of kingdom was also exercised by his successors in the East. In other words, they ruled as absolute rulers over citizens of different nationalities, who attributed divine values to them. Two were the most important kingdoms in the East, the kingdom of Egypt and the kingdom of Syria.

Kingdom of Egypt

Its founder was Ptolemy, general of Alexander the Great. In his dominion, apart from Egypt, he had the region of Cyrenaica (present-day Libya), Cyprus, which was the naval base of the state, and at times the southern region of Syria. The majority of the inhabitants of the kingdom were Egyptians, but there were other ethnic minorities, such as Jews, Persians, Greeks and Syrians.

They avoided levying taxes on the indigenous population whose main occupation was the cultivation of the land. They supported the development of trade by all means; that is why Alexandria became the largest commercial port in the Mediterranean.

Trade favored the intellectual development of the city. The Ptolemies maintained the old administrative system. They were followers of the pharaohs’ policy. They ruled collectively with a staff whose leadership positions were held by Greeks, while in the rest of the state machine they had appointed mainly natives.

The kingdom of Egypt flourished in the 3rd c. BC. From the 2nd c. BC. however, due to the exploitation of the natives, there were many peasant uprisings. At the same time, conflicts abroad, mainly with the Seleucids over the region of southern Syria, weakened the state and gradually led to its subjugation to the Romans.

Kingdom of Syria

The Seleucid kingdom was very large. It spread from the Indus to the Mediterranean and from the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf and Arabia. Because its territorial core was the region of Syria, it became known as the Kingdom of Syria.

It lacked internal cohesion and the lands in the eastern regions and Central Asia were quickly lost. The Seleucids tried to maintain the integrity of the state either with their strong army or by establishing cities where people of different ethnicities gathered4. In the beginning, the capital of the state was Seleucia on the Tigris River.

But then the center of gravity shifted to the Mediterranean and the capital became Antioch on the Orontes River, which developed into a major economic and spiritual center.

Although the political unity of the state was fictitious, nevertheless in the 3rd c. bc. the Seleucid kingdom was the largest power with a rich economy, based on agriculture and land trade. From there passed all the trade routes of the caravans that connected the markets of the East with the Mediterranean.

The Seleucids in the administration maintained the division of the Persian Empire into satrapies. Greek and indigenous officials were appointed governors.

The state, due to the separatist tendencies of the remote areas and the conflicts with the Ptolemies and the Romans, began to decline from the beginning of the 2nd c.BC.

Founding and Expansion: The Seleucid kingdom was founded by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander’s generals, who became the satrap (governor) of Babylon after Alexander’s death. From there, Seleucus gradually expanded his territory, taking control of much of the former Persian Empire. At its height, the Seleucid kingdom included regions such as modern-day Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and parts of Central Asia.

Administration: The Seleucid kingdom adopted a bureaucratic administrative system influenced by Persian practices. The empire was divided into provinces, called satrapies, each governed by a satrap appointed by the king. The central government maintained a large bureaucracy and a standing army.

Cultural Synthesis: The Seleucid kingdom was characterized by a fusion of Greek and Persian cultures, known as Hellenistic syncretism. Greek language, customs, and institutions were introduced throughout the empire, while Persian elements persisted in administration and society. The Seleucids also promoted the spread of Greek culture, particularly in the cities, which served as centers of Greek learning and philosophy.

Relations with Other Powers: The Seleucids had frequent conflicts with neighboring powers, such as the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt and the Attalid Kingdom in Anatolia. They also faced challenges from nomadic tribes in Central Asia, such as the Parthians. The empire engaged in wars, alliances, and diplomatic marriages to secure its borders and maintain its influence.

Decline and Fragmentation: The Seleucid kingdom faced internal strife, rivalries among the royal family, and external pressures from competing powers. The empire gradually lost territory and influence over time. Parthian and Roman expansions further weakened the Seleucids. The final blow came in 63 BCE when the Roman general Pompey the Great conquered Syria, effectively ending Seleucid rule.

Legacy: Despite its decline, the Seleucid kingdom had a lasting impact on the regions it ruled. Greek culture and ideas left a significant imprint on the Near East, especially in urban centers like Antioch and Seleucia. The empire also facilitated cultural exchanges between the Greek, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian civilizations.

Overall, the Seleucid kingdom played a crucial role in the spread of Greek culture and the intermixing of Eastern and Western traditions during the Hellenistic period.

The kingdoms of Greece

In metropolitan Greece the institution of the kingdom had its roots in the tribal organization of the state. The king was elected by the assembly of soldiers and was framed by a council of nobles.

This tradition was preserved throughout antiquity in the Greek tribes that did not evolve politically and were not organized in city-states, as happened, for example, with the Macedonians and the Epirotes. Thus the institution of the kingdom in them had a “national” character and maintained the standard of the proclamation of the king by the army, even when the kingdom became hereditary. In Greece, the Kingdom of Macedonia and the Kingdom of Epirus played a decisive role during the Hellenistic period.

Kingdom of Macedonia

The area of the kingdom was limited, mainly in the area of Macedonia, Thessaly and in areas of southern Greece. However, it had a cultural homogeneity and a racial organization *, based on the common origin of its inhabitants. The king was the main owner of the land, forests and mines. Much of the land the king had given as a revocable gift to nobles.

In addition to the lands that belonged to the nobles, there was also a large number of small and medium cultivators. These constituted the Macedonian army, from which the ascension of the king to the throne was ratified5. The large estates, which belonged to the king or the nobles, were cultivated by free laborers or slaves.

The kingdom of Macedonia after the disintegration of the empire was ruled by Cassander. Among the rulers who succeeded him to the throne was Dimitrios the Besieger, who occupied the throne of Macedonia for seven years (294-287 BC) and then was persecuted by Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus.

.

The kingdom then suffered from a lack of strong power and especially from the invasion of the Gauls (280 BC), a Celtic race from northwestern Europe. The Gauls, who caused many disasters in Macedonia, Epirus and southern Greece, were permanently removed from Greece by Antigonus Gonatas, son of Demetrius the Besieger (277 BC).

He became the founder of the new Macedonian dynasty of the Antigonids, who ruled until the conquest of Macedonia by the Romans (168 BC). The kings who ruled in the 2nd c. e.g. weakened the state and the rest of the Greek forces, in their attempt to impose themselves in southern Greece.

Kingdom of Epirus

The Molossians were ruled by a system of moderate kingship. That is, royal power was limited by a supreme ruler, a representative of the people. Once a year the king and the people of the Molossians gathered at their political and religious center, Passarona, where they exchanged vows of allegiance to government, in accordance with the law.

The kingdom of Epirus reached its greatest power when Pyrrhus ascended the throne, a leader with many abilities and grandiose plans. He wanted to create a state similar to that of Alexander the Great. That is why he tried to dominate the West. In five years (280-275 BC) he faced the Romans in Italy and the Carthaginians in Sicily.

However, he returned with many losses and exhausted his army in Epirus. His last plan was the subjugation of Macedonia and southern Greece. He failed in a campaign in the Peloponnese and died ingloriously during street battles in Argos (272 BC).

The changes in the city-states of Greece

The weakening of the city-state institution and the desire of the kings of Macedonia to expand to the south were the reasons that led many cities, especially isolated areas, to proceed with the formation of federal states. The new state scheme was used mainly by the Aetolians and the Achaean cities of the Peloponnese.

The political system of absolute monarchy that prevailed in Hellenistic times and rivalries between rulers did not allow the development of city-states. Thus, the city-state, which is already in decline as an organizational institution, now survives this era through the following forms:

Most city-states were absorbed by the Hellenistic kingdoms. External Link

Others formed federal states, such as confederations.

Some managed to win the favor of the monarchs and maintain their autonomy, as happened with Athens, Sparta, Rhodes, Delos and others.

Athens

After Alexander’s death Athens became dependent on the policy of the kings of Macedonia. Initially, Cassander appointed Demetrius Falireas governor of the city, who ruled (317-307 BC) as a tyrant and was later persecuted by Demetrius the Besieger.

Athens attempted a liberation struggle when Antigonus Gonatas was king of Macedonia. This struggle (267-261 BC) was led by the Athenian Stoic philosopher Chremonidis. Uprisings were attempted by other cities but their attempt failed. Antigonus Gonatas defeated the allied Greeks and captured Athens, while Chremonides took refuge in the court of Ptolemy. From then until its submission to the Romans (86 BC), the role of Athens declined politically, but culturally it continued to play a leading role.

Sparta

The way it was governed and the foreign policy of isolation that followed created the 3rd c. e.g. social and political impasse. The population of Sparta decreased. The free citizens numbered about seven hundred, and only a hundred of them had an agricultural lot7. Necessary conditions for dealing with this situation were the write-off of debts and the land reclamation of the land. The kings Agis and Kleomenis made attempts to normalize the social crisis.

When Agis IV became king (244 BC) he attempted to carry out some reforms, proposing the inclusion of the locals in the order of the Spartan citizens. His plans, however, met with a backlash from the rich, and he was assassinated. About ten years later, Kleomenis III proceeded slowly but steadily in social and political changes. These changes had an impact on other cities in the Peloponnese, where the lower classes were oppressed.

The general of the Achaean confederation Aratos, who was watching the uprisings with concern, asked for the help of the Macedonians. Kleomenis was defeated at Sellasia (222 BC), at the entrance of Laconia, by the Macedonian forces. A Macedonian guard was established in Sparta, while Kleomenis sought refuge in the court of Ptolemy.

A period of political instability and uprisings followed. Navis, a descendant of a royal family, took advantage of this deplorable situation. He imposed personal power (206 BC) and seems to have continued Kleomenes’s reform work. However, he met the reactions of other Greek cities that were afraid of the spread of the reforms. His assassination (192 BC) sealed the end of the autonomy of Sparta, which from then until the Roman conquest became a member of the Achaean confederation.

Rhodes. Its great growth is due to the economic circumstances that were formed after the death of Alexander the Great. Its geographical location and navy helped it to develop into a large commercial center. The strong wall and the foreign policy of Rhodes were two factors that determined the historical course of the island during the Hellenistic times. At the end of the 4th c. BC, repulsed the attack of Demetrius (305-4 BC). From the siege of Rhodes, Dimitrios took the name Besieger.

Rhodes

Rhodes formally had a democratic state. But it was essentially ruled by wealthy merchants and bankers. In times of crisis, the rich, in order to avoid social uprisings, undertook the diet of the poor8.

Its power seems to have been calculated not only by the Hellenistic kingdoms but also by the rising Rome.

Rhodes allied with it against Antiochus III of Syria. In return, the Romans ceded Lycia and part of Caria. But when it later sided with Macedonia, Rome’s main rival, the Romans captured Lycia and Caria and declared Delos a free port * (167 BC) with the aim of depleting it financially. From then on the Rhodian state began to decline and was eventually enslaved by the Romans (43 BC).

Delos

The sacred character of the island contributed to its gradual development into a financial center. Its current geographical location, in the center of the Aegean, aroused the interest of kings. At the end of the 4th c. BC, when the naval power of the Athenians declined, Delos passed into the sphere of influence of the kings of Macedonia. This was the period of its economic growth.

Typical examples of the commercial activity of the island were the creation of public and private banks and the recognition of the port of Delos as an important station of the transit trade of the Eastern Mediterranean.

In 167 BC. the Romans, after conquering the kingdom of Macedonia, declared Delos a free port. while granting the supervision of the island to the Athenians. The Delians were expelled and the new inhabitants who began to flock contributed to its economic development during the second half of the 2nd c.BC. In fact, the influence of Athens was minimal; the life of Delos was now defined by foreigners, Greeks from other cities. Egyptians, Syrians, Phoenicians, Jews, Italians. But they were all under the supervision of Rome.