History of Ancient Greek Art

Ancient Greek art developed and flourished between between 1000 – 31 BC in mainland Greece and in the Greek colonies of the eastern Mediterranean, southern Italy, Sicily, and the Aegean.

The earlier date is associated with the transitional period following the decline of the prehistoric Minoan and Mycenean civilizations (see Aegean civilization. Minoan art), the Battle of Actium in 31 BC represents the time of transition into Roman art.

Greek art developed within the framework of the Greek city-state, the evolution of which falls into the chronological period defined above.

The Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders, which had profound influence on the history of architecture, developed in monumental Greek religious and civic architecture.

Greek sculpture progressed from stylization to naturalism and from naturalism to realism, creating some of the greatest works in the history of art. Greek painting developed in two channels: monumental painting and painting on pottery.

Because little remains of the former type, scholars rely chiefly on vase painting to trace the development of Greek drawing. The early study of Greek art, which was seen mainly through the works of Roman copyists, had enormous influence in 16th-century Italy and was of fundamental importance in the development of Renaissance art and architecture.

GEOMETRIC PERIOD (10th – 8th BC)

The material remains of the new culture are rather sparse: there is little surviving monumental architecture, which was primarily in the form of primitive temples. no wall painting. and no large-scale sculpture.

Existing sculpture is small, mostly bronze, terra-cotta, or ivory statuettes that served as dedications at religious sanctuaries or as grave offerings. Pottery, however, is plentiful and, particularly in Attica, of good quality.

The geometric period is named for the pottery’s geometric decoration. Bands of decoration drawn in black on the light-colored clay included a rich repertoire of geometric designs, such as meanders, swastikas, chevrons, and elaborations of these patterns.

Animal forms began to intrude gradually into the abstract decoration, and by the 8th century BC human figures appeared in stylized silhouette. These figures included dancers, processions of horsemen and chariots, battle scenes, and men and women lamenting the dead, as in the Dipylon Krater (8th century BC. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City), a large vase that was originally used as a grave monument.

Much rarer and more expensive was ivory, the processing of which the Greeks learned in the East. This sought-after material came mainly from Africa, traveling long distances.

Ivory works often have oriental patterns. A typical example is a statuette of a naked goddess found in a tomb of a rich woman from around 740 BC. in the Kerameikos cemetery in Athens.

The “naked goddess” comes from Syria and the Greeks got to know her from their travels in the eastern Mediterranean and from the Phoenician traders who came to their country.

Interestingly, the statuette of Kerameikos, for all its close connection with Syria, is a Greek work made according to all indications in Attica, but based on Eastern models. Another important part of the art of the geometric age (but also of ancient art in general), of which very few examples have survived, is wood carving.

ARCHAIC PERIOD (7th- 6th BC)

The beginning of the archaic period is sometimes called the Orientalizing phase because of the great influence of the Near East on the figurative arts. The full development of the polis, or city-state, occurred during the archaic period. The cities, through colonization and trade, became acquainted with Egyptian stone carving and the decorative arts of Assyria and Mesopotamia.

Painting

The Eastern motifs, probably transmitted through imports of metalwork or textiles, blossomed into a painting style that replaced the geometric style in pottery decoration.

The abstraction of the geometric vases, in which the human and animal figures were subjugated to the overall design, disappeared. Human figures appeared in compositions that told a story, often a familiar one from Greek legend, and inscriptions painted on the vase identified the heroes and divinities represented.

Corinth was the most important pottery center. Corinthian miniature vessels for perfumed oil, as well as larger vases, were exported in great quantities during the 7th and 6th centuries BC. By the middle of the 6th century, however, Athens assumed the lead in the pottery industry.

Athenian potters experimented with different techniques, such as silhouette, outline drawing, and the use of white in their vase paintings. They gradually concentrated on black figure, a technique borrowed from the Corinthian animal style.

The black-figure style consisted of painting figures in silhouette on a light ground and then incising details in the black with a fine instrument. Black-figure vases were decorated with scenes from mythology as well as from daily life.

The style, which was particularly suited to a decorative medium such as pottery, was used by numerous excellent artists, some of whom signed their vases, as did Cleitias, the painter of the Franois Vase (c.570 BC. Archaeological Museum, Florence).

The best black-figure artist was Exekias, who painted elegant and sometimes somber scenes on vases and terra-cotta plaques an amphora that shows Achilles and Ajax playing at draughts (c.550-540 BC. Vatican Museum, Rome) is particularly noteworthy.

During the late archaic period, about 530 BC, the red-figure style was introduced. In this technique the background of the picture, rather than the picture itself, was covered with black glaze.

The figures were preserved in the color of the clay. details were painted rather than incised on the light ground. This technique gave painters greater freedom to perfect their rendering of anatomy and perspective.

Sculpture

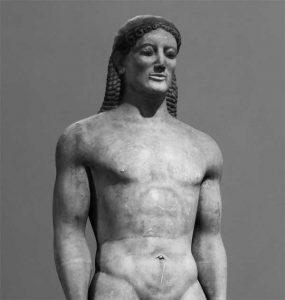

Greek sculptors used the prototype of a standing figure with one foot advanced and the hands clenched to the sides and developed it so that within a hundred years the same general type was no longer stylized but had become a naturalistic rendering with subtle modeling.

The female equivalent, or kore, is always dressed in rich drapery enhanced by incision and color. Color was also used for the hair and facial features of both male and female statues.

The figures do not seem to represent a divinity, nor are they normally portraits, but instead are images of the ideal masculine or feminine form.

The great artists of the period also created other types of sculpture. the Rampin Horseman (c.560 BC. Acropolis Museum, Athens. the head is in the Louvre, Paris) was an early example of a man-animal composition.

The architectural sculptures, which were carved in relief or in the round and designed to decorate stone temples, were even more complex. Early gable sculptures show a predilection for monsters. the limestone statue of a three-headed monster (c.560-550 BC. Acropolis Museum), striking in the preservation of its gay colors, belonged to such a gable.

Gradually fighting scenes began to predominate, as in the late-6th- or early-5th-century gables from the Aphaia temple on the island of Aegina (Glyptothek, Munich). Battle scenes were used to decorate the frieze of the marble treasury dedicated to the sanctuary of Apollo by the island city-state of Siphnos (c.525 BC. Delphi Museum).

In these reliefs, as well as in freestanding statues, there was a striking clarity of contour and a predilection for pattern that characterize archaic sculpture.

Monumental Greek architecture was a development of the archaic period that coincided with the beginning of monumental sculpture. During this period the Doric style of mainland Greece and the western colonies and the Ionic style of the Aegean islands and the Ionian colonies came into being. Both styles reached their culmination in Attica during the 5th century.

CLASSICAL PERIOD (5th-4th BC)

The culmination of the tendencies of the preceding centuries in all fields of art occurred during the classical period. The standardization of the temple form permitted only minor innovations chiefly in the ornamentation of buildings, including the creation of the Corinthian order and Greek architects turned their efforts toward creating the subtleties of proportion that were to make Greek architecture one of the greatest in the world.

Sculpture

The temple of Zeus is a Doric building, imposing in size and in the magnificence of its architectural sculpture.

The compositions on the two gables and on the metopes over the inner porches are representative of the early-5th-century severe style, with rather simple, severe forms heavy drapery, an interest in emotion and characterization and contrasts of texture and age.

The Doric architecture of the Parthenon was tempered by Ionic intrusions, including the Ionic frieze. Most of the frieze is in the British Museum in London, together with some of the metopes and gable figures

Although executed by many artists, it was conceived by one designer, probably Phidias, the eminent Athenian sculptor who was the overseer of the building program on the Acropolis and who created the gold-and-ivory cult statue of Athena for the Parthenon.

Because of a lack of original works by the great sculptors of the 5th century BC Myron and Polyclitus and of the 4th century BC Lysippus and Scopas scholars rely mainly on Roman copies and on ancient descriptions. One possible exception is the Hermes and the Infant Dionysus (c.340 BC. Olympia Museum, Greece), which is believed by some to be an original.

Classical sculpture was characterized by a more relaxed attitude of the human body, with a balanced composition, idealized treatment of the head, and increasingly slender proportions.

Some great bronzes have survived, such as the Charioteer of Delphi (c.480 475 BC. Delphi Museum) and the Zeus, or Poseidon, of Artemision (c.460 BC. National Museum, Athens).

Painting

No trace exists of the work of the great painters of the classical period Apelles, Micon, Parrhasius, Polygnotus, and Zeuxis. A pale glimmer of their type of work can be discerned in the drawing of the vase painters who worked in the red-figure style and in the white-ground technique suitable for grave offerings.

The vase painters perfected the rendering of anatomy and introduced and developed perspective and shading. The Berlin Painter, the Brygos Painter, the Niobid Painter, and the Penthesileia Painter are just a few who worked in Athens, especially during the earlier years of the period, when red-figure ware was at its best.

HELLENISTIC PERIOD (323- 31 BC)

After the death (323 BC) of Alexander the Great, his extensive empire was dissolved into many different kingdoms. This fragmentation was symbolic of the diversity and multiplicity of artistic tendencies in the Hellenistic Age. The great art centers were no longer in mainland Greece but in the islands, such as Rhodes, and the cities in the eastern Mediterranean Alexandria, Antioch, and Pergamum.

Sculpture

The variety of artistic directions makes a general statement about the sculpture of the period rather difficult. There was a tendency toward classicism, but also another toward the baroque or even the rococo. a tendency toward idealization, but also a tendency toward realism. The Hellenistic period was, above all, a period of eclecticism.

Art still served a religious function or to glorify athletes, but sculpture and painting were also used to decorate the homes of the rich. There was an interest in heroic portraits and in colossal groups but also in humbler subjects. The human being was portrayed in every stage and walk of life. there was even an interest in caricature.

The awareness of space that characterized architecture also began to emerge in sculpture and painting.

As a result landscapes and interiors appeared for the first time in both reliefs and painted panels.

The great Altar of Zeus from Pergamum (c.180 BC. State Museum, Berlin), created by Greek artists for King Eumenes II, was enclosed by a high podium decorated with a monumental frieze of the battle between the gods and giants. Many Hellenistic tendencies were realized in this work.

The basis for its iconography was firmly rooted in classical tradition. The baroque style of the sculpture was characteristic of the time in its exaggeration of movement, physical pain, and emotion, all set against a background of swirling draperies.