Introduction to Aeschylus Tragededy Prometheus Bound

Prometheus Bound is a tragic play attributed to the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus, believed to have been written between 463 and 456 BC.

It is part of a now-lost trilogy that dramatized the myth of Prometheus, a Titan who defied Zeus to bring fire and knowledge to humanity. This play is a cornerstone of ancient Greek literature, renowned for its complex themes, vivid character portrayals, and profound exploration of human suffering and divine justice.

Prometheus Bound, is the only surviving tragedy in which none of the characters is a common mortal, differs markedly from the rest of Aeschylus’ tragedies. Several scholars – perhaps the majority – consider the work a pseudograph.

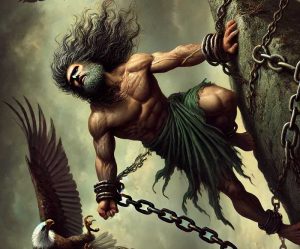

At the beginning of the play, Kratos and Bia, together with the reluctant Hephaestus, carrying out the order of Zeus, lead Prometheus to a desert part of Scythia and impale him on a rock, because he stole from the gods fire and give to the people.

At that place the Oceanids (the dance) arrive in turn, who heard the heavy pounding, the sympathetic Oceanus, who advises Prometheus to change his rigid attitude towards Zeus and offers himself to help, the “homeopathic” Io, the daughter of the king of Argos Inachus, whom Zeus fell in love with and who now, transformed into a cow, wanders endlessly, chased by the oistron (the fly) sent by Hera.

To these visitors Prometheus tells of the help he rendered to Zeus, of his offering to men, of his martyrdom, of their own future fate (Io), and of some secret he possesses concerning the impending fall of Zeus, the which only he could prevent. Last comes Hermes, an emissary of Zeus, who unfairly tries to extract from Prometheus the secret he knows with threats. He stubbornly refuses and is crushed by Zeus’ thunderbolt.

The following excerpt is from the second episode, the only episode of ancient tragedy during which no person appears or leaves. Prometheus addresses the dance of the Oceanids and talks about his crucial inventions and his general contribution that made human evolution possible. In particular he mentions architecture and carpentry, meteorology and astronomy, the invention of numbers and writing, the domestication and fermentation of animals, navigation, medicine, foretelling the future in various ways, and metallurgy.

Literary and Historical Context

It is of great interest that Prometheus’ captives are Kratos (Power) and Violence, which, as Aeschylus argues, are directly associated with power. By personifying these two situations, state power and state violence, it opens up a big issue that is always topical.

It is of great interest that Prometheus’ captives are Kratos (Power) and Violence, which, as Aeschylus argues, are directly associated with power. By personifying these two situations, state power and state violence, it opens up a big issue that is always topical.

Do the laws of the state exercise violence or not? Aeschylus, who lived in democratic Athens, where human rights were absolutely guaranteed, has every right to raise the issue. On the other hand, the rule of Zeus, after two victories against the Titans and the Giants, seems authoritarian but from a point of view appropriate.

In the specific case of Prometheus as Bound, there is great concern as to whether the need for safe governance justifies such an authoritarian behavior, especially in a God who wanted the good of people. On the other hand, because Zeus and the other gods did not want the progress of man and selfishly keep for themselves the cause of the creation of technical civilization, namely fire.

Prometheus’ attitude towards Zeus is haughty and not slavish, as e.g. of Hermes. One could say that Prometheus has Zeus in his hand, because he holds a secret, which concerns the dethronement of Zeus, which he himself did to his father Saturn. So he prefers to remain chained and devoured by the vulture, and not to reveal his secret, despite the threats thrown by Hermes, the subordinate of Zeus

Themes and Analysis

Defiance and Rebellion

Prometheus’s defiance against Zeus is the play’s central theme. By giving fire to humanity, Prometheus empowers mankind, symbolizing the spark of knowledge and enlightenment. This act of rebellion challenges the authority of Zeus, raising questions about tyranny, justice, and the legitimacy of power. Prometheus emerges as a heroic figure, willing to endure eternal punishment for the sake of humanity’s advancement.

Suffering and Endurance

Prometheus’s suffering is depicted in vivid detail, highlighting the theme of endurance in the face of overwhelming adversity. His unyielding spirit and refusal to submit to Zeus’s will resonate with the audience, embodying the human condition’s resilience. The play delves into the paradox of suffering as both a source of strength and a manifestation of injustice.

Divine Justice and Injustice

The conflict between Prometheus and Zeus underscores the tension between different conceptions of justice. Zeus’s punishment of Prometheus appears excessively harsh and tyrannical, prompting the audience to question the morality of the gods. Prometheus, despite being a god himself, represents a more compassionate and humanistic approach, advocating for mercy and understanding over retribution.

Knowledge and Power

The gift of fire symbolizes knowledge, technology, and progress. Prometheus’s act of giving fire to humanity is a double-edged sword, bringing both enlightenment and potential danger. The play explores the transformative power of knowledge and its capacity to challenge existing power structures. It also reflects on the responsibilities and consequences that come with the acquisition of knowledge.

Isolation and Companionship

Throughout the play, Prometheus’s isolation on the desolate rock serves as a powerful symbol of his alienation from the divine order. However, his interactions with the Oceanids, Io, and other visitors provide moments of companionship and solidarity. These interactions emphasize the importance of empathy and connection, even in the face of profound suffering.

Characters

Prometheus

Prometheus is depicted as a complex and multi-dimensional character. His defiance, compassion for humanity, and willingness to endure suffering for a greater cause make him a tragic hero. His foresight and wisdom contrast sharply with Zeus’s authoritarian rule, highlighting his role as a champion of human potential.

Zeus

Although Zeus does not appear on stage, his presence looms large throughout the play. He is portrayed as a distant and punitive ruler, embodying the arbitrary nature of divine authority. Zeus’s actions raise questions about the legitimacy of his rule and the ethical implications of his decisions.

Hephaestus

Hephaestus’s role as the reluctant enforcer of Zeus’s punishment adds a layer of complexity to the narrative. His sympathy for Prometheus and discomfort with his task underscore the moral ambiguity of the gods’ actions.

Io

Io’s appearance in the play serves as a poignant reminder of the collateral damage caused by divine conflicts. Her suffering and transformation by Zeus exemplify the arbitrary and often cruel nature of the gods’ interventions in human lives.

Hermes

Hermes, as the messenger of Zeus, represents the voice of authority and the enforcement of divine will. His interactions with Prometheus highlight the irreconcilable differences between the two characters’ worldviews.